How many of you feel oppressed by members of the so-called baby boom -- that explosion of American birth that began when the young GIs returned home triumphant from the twin theaters of war in Asia and Europe? The first things that generation did -- not necessarily in this order -- were invent suburbia, get wives and begin procreating like crazy. This activity flourished throughout the dark ages of the Cold War, peaking with 4,300,000 births in 1957.

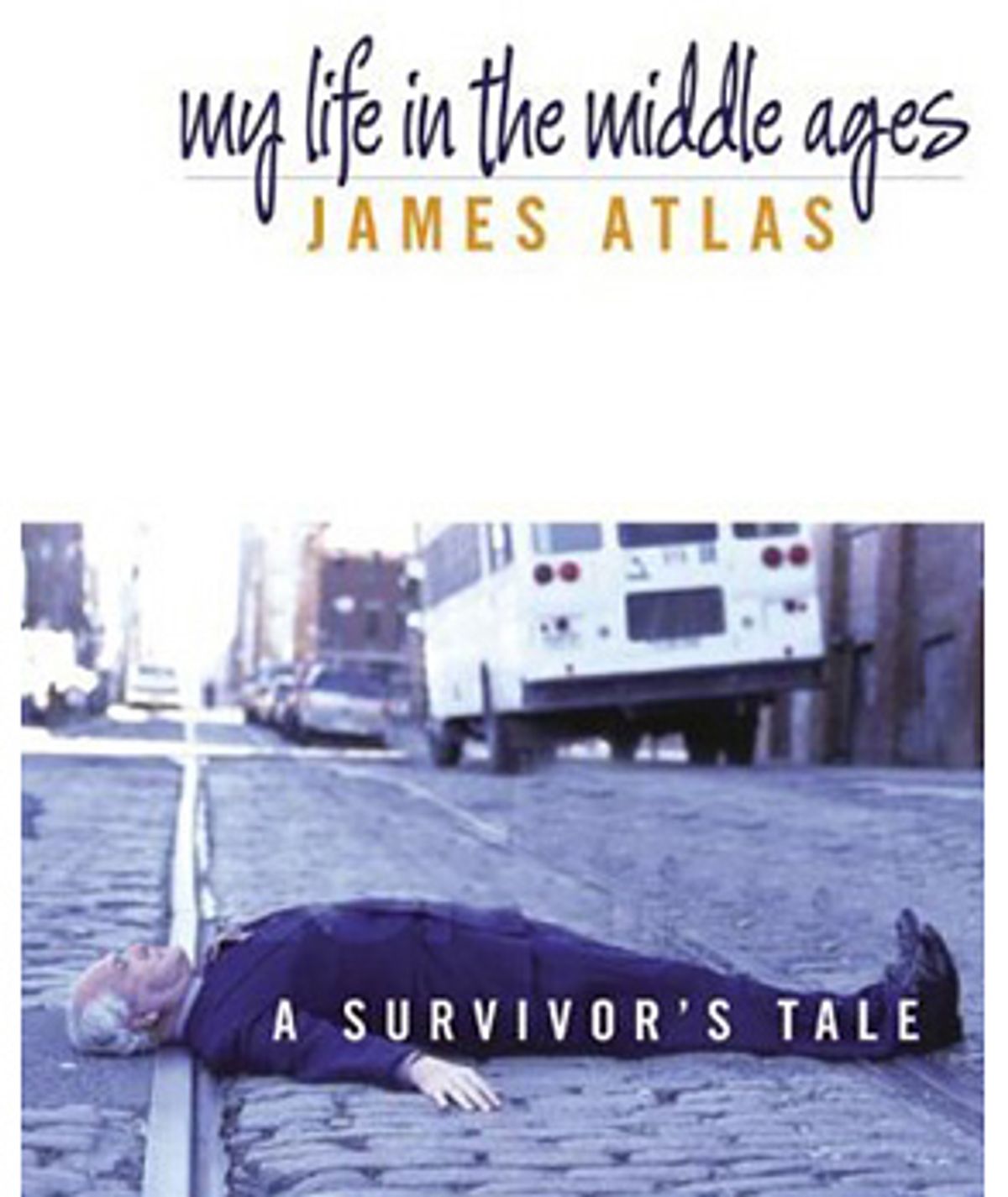

I believe we can authoritatively state that the baby boom itself began during June of 1946, the month when "The Pocket Book of Baby and Child Care," by Benjamin Spock, first went on sale for 35 cents. This date dictates that the oldest official member of the baby boom is 59 years old. The youngest is in his or her early 40s. Only now has one of these boomers dared to chart the course of modern middle age -- the novelist/biographer/critic/publisher James Atlas. His semi-memoir is titled "My Life in the Middle Ages." The cover does not show a robust man swatting a tennis racket, or a wavy-gray-haired fellow nuzzling a blonde half his age, tossing away his bottle of Viagra over his shoulder. No, the cover shows a heavy-set man with a gray, receding hairline lying down on a brick street.

Atlas chose the cover image for his book. The man has a sense of humor about his condition. The raw material of Atlas' chapters, however, began as soulless exercises edited by Tina Brown, back in the days when she was the modern Marie Antoinette/mantresse running the New Yorker. She encouraged Atlas to bellyache about the lack of privilege the privileged middle-aged citizens of New York believed they were suffering. (Let them eat brioche!)

Thankfully, a few years after Brown left the New Yorker to start the now-defunct Talk, Atlas rethought and rewrote the essays, discovering a genuine humanistic angle for the genre he was inventing -- the middle-aged coming-of-age story. In his book's introduction, Atlas recalls his father's 50th birthday party: "[My father] announced to his assembled friends that he was now on the downward slope of the bell curve. At fifty you could just make out the far horizon and what lay beyond it -- 'Twilight and evening bell, and after that the dark.'"

Apparently, Dylan Thomas' proclamation, "Do not go gentle into that good night ... Rage, rage against the dying of the light," is easier recited than followed. What the younger Atlas discovered was, "The greatest challenge of middle age -- and as I write these words, I'm on the threshold of late middle age, which imposes a biological deadline far more terrifying than the demands of any editor -- is to accept one's limitations. It's not easy. In my experience, it's the hardest thing of all."

The author's blunt chapter titles concisely sum up the contents of the book: "Mom and Dad," "Time," "Home," "Money," "Failure," "Shrinks," "The Body," "Books," "God," "Twenty-fifth Anniversary." The chapters are poignant. Also, Atlas can laugh at himself. But there is no light at the end of the tunnel. The last chapter is titled "Death." I suppose it's a hopeful sign that "Death" is followed by "Acknowledgements."

I met with Atlas in his Manhattan skyscraper office with a view of a thousand orange shower curtains flapping down in Central Park. Whatever "limitations" the 55-year-old Atlas -- who presides over his own imprint, Atlas Books, at HarperCollins -- may have, they are not physical ones. He is trim and dapper and looks to be in his mid-40s. Christ! He still has all his hair. I knew that Atlas had experienced both literary triumphs and bile in his career, yet, when I talked to him, he refused to really bad-mouth anyone. By the interview's end, I did, however, discern a hidden Truman Capote vibe in Atlas. And by that I'm thinking of the famous photograph of Capote filing his fingernails with a stiletto. There was a quiet edge of danger about Atlas. This man does not appear to be someone who plans to be going gentle into any damn good night anytime soon.

Are you prepared to be the spokesman for your middle-aged generation?

No. I'm comfortable being a spokesman for myself. I did not wish to write a memoir as such. I didn't want to write a book that was revelatory in that way. My book has resonance beyond me. I wanted to write in a way that allowed me to write about my generation.

So how old do I look?

I don't know. Significantly younger than I am. Say, late 30s.

I'm 47. So I'm middle-aged?

Sorry. But you are, yeah. You're middle-aged, definitely.

Does anyone fear you?

Fear me? You've got to be kidding.

My father told me that the mark of success when you're middle-aged is to be powerful enough that a number of people fear you professionally.

I suppose people used to fear me when I was a smart-alecky book critic for the New York Times. Who would fear me now? I can see what you're getting at, but I can't stand the idea of frightening the people who work for me because I've had plenty of jobs where I've been bullied. It's a very unpleasant experience. I have potential power as a father, but I don't exercise it. As an editor I have potential power to insist on certain changes, but because I'm also a writer, I don't want to do that.

So when you go to dinner parties, do you encounter writers you once panned in reviews or writers who have insulted you?

It happens. At one event my wife was talking to this man and admiring his little baby, and he was someone who had written very unkindly about my work. I hustled over to her and said, "Stay away from that so-and-so!" [Laughs.] It happens. But I'm not at war the way I used to be. I don't walk into a room and feel anxious. Unless I'm mistaken, there seems to be a measure of goodwill. Also, as we get older we have fewer impulses to quarrel. That wasn't true of the older generation.

Enemies. That's akin to having people fear you.

My friend John Irving once said something great, "If you don't have enemies, you haven't lived." So I've lived a full life.

You came of age during the 1960s. How rebellious were you?

Terribly. That's why I have trouble with my kids who are normal. I just can't believe that they're not stoned and god knows what else. I explained that to my 17-year-old son last week when I was concerned that he was roaming around this hotel with some girls from Albany. It turned out they were just looking for a board game. And I believed him. He said, "Why don't you trust me." I said, "Because when I was your age I was stealing Heineken out of my father's refrigerator in the garage and storming off in our car to smash it up."

It's strange how finely calibrated the baby boom is, because my brother, who is 60, missed the 1960s on the early side. I was in the middle of it. I was in Chicago in '68. I was in the march on Washington. The riot in Tompkins Square. I wish I did more, though. I had a VW van and I wished I'd painted it in psychedelic colors.

No one could tell by looking at you today that you once had long hair and smoked dope. Are there any middle-aged contemporaries who were and still are squares -- kids who had bought the Goldwater line of 1964?

I can't think of any. But back then there were no squares. That category didn't exist. We were uniformly nonsquare. I myself wanted to be a poet. I didn't know that you can't be a poet in America, that poets have no function in our society. In terms of being in this office and having my own company -- that was never an ambition. Never.

In the failure chapter in your book you describe the humiliation of getting fired at age 50. Was that about the New Yorker?

I don't want to go into the specifics of it.

But you obviously got a second chance. In American mythology you always get another chance.

Yes, that is so true. That widely quoted axiom of F. Scott Fitzgerald, "There are no second acts in American lives" -- that's ridiculous. There are as many acts as you are around for, it seems to me. I've had many "acts." And I hope to have more. Also, the difference between getting it right and getting it wrong is so razor thin.

You've written that when you were writing this book you ran the text by a lot of people. Was there much that they said, "You can't say this. You gotta take it out."?

I had a lot of trouble with this book. I kept trying to do it right. There was a period about a year ago when I thought the book was a disaster and I wanted to pay back my advance (but I couldn't afford to!). My friends and family helped me salvage the manuscript. I take a lot of editing. I listen. I've had great good fortune [with regard to editors]. The editor of my first biography, of Delmore Schwartz, was perhaps the greatest editor of his generation: Dwight Macdonald, who happened to be Delmore's executor. For my biography of Bellow, I gave it to -- I can say this because he's dead now -- the most unpleasant and curmudgeonly guy I could dig up, Edward Schils, who was part of Bellow's circle. Schils wrote me a 16-page single-spaced memo tearing apart my book, eviscerating it. I thought, "Better him than Christopher Lehmann-Haupt."

The New York Times book critic! Is he still alive?

Let's not get into him. He writes the obits.

Oh. Because I never see his byline.

I hope you never do again. [Pause.] That's not fair. He was nice to my first book. And my second book wasn't very good.

In the book you mention the New Yorker article Tina Brown assigned you about being the only citizen in Manhattan who was still having fun in the 1990s.

I don't remember being assigned that piece because I had a reputation for having fun or a reputation for not having fun. In my life I've had a lot of pain and a lot of fun, but something I haven't had is being so deep, deep down that I couldn't still enjoy myself.

In California terms, having a good time might mean hang gliding. In Manhattan, having fun has traditionally meant going to exclusive and expensive clubs or restaurants with one's exclusive friends.

The point I was making was that the '90s culture was changing and people were obsessively work oriented.

How do you imagine people who do not live in New York will relate to the book?

That's a good question. I don't know. Most of the people I've heard from live in New York. When I wrote the pieces for the New Yorker I heard from people all over the country. If only people in New York like the book, that's OK. There are a lot of people in New York.

Who is the guy on the cover?

I don't know. I got the photo out of a computer archive. I typed in "sad middle-aged men" and hundreds of images came up, images of men staring out windows, sitting alone, walking down the street in the snow. And then I saw this fellow lying in the street. Has the trolley passed him over or has it missed him? But he survived so ... I wonder who he is. People sometimes say, "Where did you get that guy?" Maybe he'll write to me.

Until I met you in the flesh, I had assumed you posed for the cover yourself.

I'd never do that. I set out to write about experiences I had without being overly confessional. You notice when I write the chapter called "Shrinks," I don't go into what I was actually talking to those psychiatrists about. This is why if what I wrote about strikes a chord, I feel lucky. One thing that pleases me is that women seem to like the book as much as men. I didn't want to write one of these Jewish coming-of-age novels.

Is Jewish machismo different culturally than WASP machismo?

[Laughs] I didn't think it existed. But in fact it does. My friend Rich Cohen writes wonderfully about Jewish machismo. He wrote "Tough Jews: Jewish Avengers." He's great. I'm not an authority on that. I write about Jewish weaklings.

But in terms of admitting weakness or disappointments, you're either offhanded about it or you just kvetch. There's a Jewish way to admit that you've fucked up without admitting shame that a goy would feel.

Is that true? I suppose there is a kind of self-irony to Jewish social characters.

Irony! That's the word. Because WASP America doesn't "get" irony.

Because this is a very success-oriented culture. A number of people have told me that they've been fired or their friends have been fired and no one will write about it. This seems an almost universal experience. Everyone's been fired. When I first wrote about failure in the New Yorker, I got letters from the most famous people you can imagine -- household names -- you couldn't believe they thought of themselves as failures.

Is being swamped with regret a symptom of middle age or old-man-hood?

I think everyone has regrets. In the 1960s, I was on a tennis team and was a ranked player in the Midwest. This was one of the deleterious effects of the 1960s -- it was uncool to be in sports. I regret that I didn't play tennis again for 20 years.

Your book makes it sound like when you play tennis today you exhibit machismo aplenty.

I certainly want to win. I play three times a week if I can get away with it. I play a wonderful guy retired from Morgan Stanley, a broker. He's 70 and in phenomenal shape. He trounces me. I don't think I want to win enough. I have trouble closing. When it comes right down to it, I fight all week long. When I get to the court, I can't just struggle enough to win in another arena. So I lose a lot when I shouldn't.

There is no room for irony when you're playing tennis.

No, there isn't. There's room for neurosis. Like my son says to me once, "Dad, I figured out what's wrong with your game?" I said, "What?" He said, "You're crazy."

So tell me the truth -- weren't you disappointed that your son was searching for a board game as opposed to finding a quiet spot to get it on with the Albany girls?

No! I thought that was really sweet.

Or else he knows how to play you for a sucker.

[James Atlas thinks about that one.]

Shares