The American honeymoon in Afghanistan may be over. Until last month the Bush administration could take comfort that Afghanistan was everything Iraq was not. Its population was generally pro-American and grateful for the U.S. intervention. Afghan President Hamid Karzai was happily beholden to the advice of the U.S. ambassador. Even Afghan prisoners released from the U.S. prison in Guantánamo seemed for the most part to have no hard feelings and simply went home. Now a wave of violence, much of it aimed at foreigners, has changed the mood in the country.

Anti-American riots swept Afghanistan in May for the first time since the U.S. invasion in 2001 after Newsweek printed allegations that a Quran had been flushed down a toilet at Guantánamo. But before the riots, Kabul, the capital, had already become a less friendly place for foreigners. My own calm was shattered when I checked into the Park Residence hotel on May 7. I had just unpacked my bags when a single thunderclap sounded from across the courtyard. It wasn’t a big explosion, and I almost believed the hotel clerk who said he thought the boiler had blown. It turned out that a suicide bomber had hit the hotel’s Internet cafe, where foreign workers for nongovernmental organizations often go to check their e-mail.

By the spray of blood on the walls, it looked as if the bomber had stepped into the lavatory, perhaps to arrange his explosives, which then detonated prematurely as he stepped back into the cafe. The explosion killed two people in addition to the bomber and blew shards of glass into the street. After a quick look I fled to my room, fearing a second, bigger bomb — a common tactic. But the bomber had been alone.

Although aid workers and U.N. officials are loath to accept it, the party mood is over. In the past month there have been four attempts to kidnap foreigners in the center of Kabul. One was successful, and Italian aid worker Clementina Cantoni remains a hostage. Her captors’ videotape demanding ransom evoked the videos released by insurgents in Iraq, where occupying soldiers and foreign humanitarians are all considered fair game.

But the riots, which spread to half a dozen provinces, were a wake-up call. The targets, as usual, were mostly international aid organizations — the only soft targets available. The government tried to blame the riots on elements of the Taliban, a plausible explanation in eastern provinces like Nangarhar and Laghman but less so in provinces like Badakshan or Tachar, which are still dominated by members of the Northern Alliance, who fought alongside the United States to oust the Taliban in 2001.

The violence has “made us rethink. We have to think about the safety of our staff. If that means that [Afghan] communities suffer — we have to balance,” said Nik Rilcoff, country director for the British charity Merlin. On the day I met with her, five Afghan employees of a U.S. company had been killed in the south. The next day six more were massacred while escorting their co-workers’ bodies home. Rilcoff said she is torn between keeping up the charity’s aid work and protecting its workers.

The demonstrations in Kabul were mild in comparison to those in the provinces. About 500 students marched up and down the main boulevard at Kabul University as dozens of riot police made sure they didn’t move east into the city proper, where things would have certainly gotten bigger and less predictable.

Handing out fliers of the now iconic pictures from Abu Ghraib prison, one demonstrator, Muzaid Karim, told me, “When they started to attack Islamic values the Afghan people couldn’t tolerate it. If things continue, then the [friendship between the United States and Afghanistan] will be in serious trouble.”

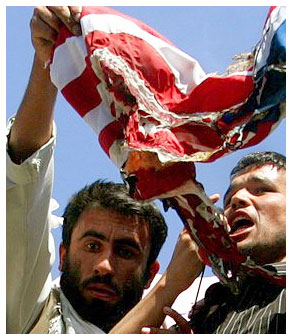

Toward the end, the demonstrators turned to that great symbol of freedom of expression around the world — the burning of an American flag. But they lacked the forethought to soak it in gasoline. Eventually, by burning a bundle of their pamphlets and roasting the flag, they managed to get it going.

Worked up, the crowd began yelling “Death to Bush,” “Death to America” and “Long live Islam.” I asked Omar Samir, who was yelling “death” the loudest, if the Americans hadn’t done a few things to help his country. “What is helping? In four years we haven’t seen any major changes in Afghanistan … Just the turbans are nowhere to be seen,” he said, meaning the Taliban.

The slow pace of reconstruction isn’t the only gripe. Afghans were angry about the abuse of the Quran, but they seemed more concerned about the agreement on U.S. military bases that President Karzai would soon be signing in Washington, and about the detention of Afghans at Guantánamo and the two U.S. military prisons in Afghanistan.

Afghans in the past have not seemed to share the rest of the Muslim world’s outrage about America’s detention of so-called enemy combatants in its war on terror. Perhaps because of the way different factions in the Afghan civil war often tortured and murdered prisoners, U.S. detention methods seemed relatively tame to them.

Some 50 Afghan prisoners were released this week in what the U.S. military called a goodwill gesture, and about 80 were released at the beginning of last month. I tracked down one of the released detainees, a man named Shireen Anwari, in his hometown of Gardiz. Anwari told me a now familiar story of having been arrested in the middle of the night, apparently after being denounced as a terrorist by one of his neighbors. Anwari said he was held at Bagram Air Base, north of Kabul, for 14 months and then released without charge. Although his treatment in prison had recently improved, he said, he’d previously been forbidden to speak for months at a time. If he broke the rule he’d be forced to stand with his arms in the air or in other stress positions for hours on end.

Anwari’s story is consistent with that of numerous other detainees and is hardly the worst tale to come out of Bagram. According to Human Rights Watch, at least nine detainees have died at Bagram, some of them beaten to death by U.S. guards. (The worst of the abuses were committed in 2002, by soldiers who later were transferred to Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison.) After an hour of answering my questions, Anwari had just one for me.

“Why are you asking me all of this? Everyone knows that the Americans are doing these things. And no one is going to do anything about it,” he said.

For a while, though, it did look as if someone — none other than President Karzai — was going to do something. Karzai has long been seen as a puppet of the United States, and indeed, he was handpicked by the United States to lead Afghanistan’s interim government. But since his election last October, Karzai has been trying to strike a more independent pose — and the unrest in Afghanistan seemed to provide the perfect moment for him to do so.

When the riots happened, Karzai was in Europe hitting up donors for cash. He came home righteous and angry. First he scolded his countrymen for making him look bad. But then he said — in public for the first time — that the Americans had made mistakes. “Afghanistan is no longer owned by anybody else. We are the owners of our country,” he said.

He then challenged the Bush administration in a way not even close allies like Tony Blair of Britain and John Howard of Australia have done in public — saying all prisoners would be turned over to Afghan control and that U.S. military action in Afghanistan would now be subject to the approval of his elected government.

“We have told the Americans that we don’t want them anymore to go to people’s houses and knock down doors and arrest people without our permission. We have told them, Stop!” Karzai said, “No operation should be conducted in Afghanistan without the permission of the Afghan government.”

Afghans loved it. One newspaper declared that Karzai had finally stood up to the USA.

The timing of his sudden show of defiance was impressive: He was scheduled to meet with President Bush in the White House just a week later, on May 23. Afghans and ex-pats in Kabul theorized that before his big trip to Washington, Karzai had pushed through a deal with the Americans and that Bush would yield to his demands to increase Karzai’s prestige.

If the plan was to make Karzai look good, someone neglected to tell Bush. The president met with Karzai and thanked him for his commitment to freedom and for taking such good care of the first lady when she visited Afghanistan.

As for substance, Bush gave Karzai zero. He said America would continue to “consult” with Afghanistan about U.S. military operations and continue to “work our way through” the Afghan prisoners in places like Guantánamo. Karzai smiled and said he hoped that Bush would come to Kabul sometime soon.

When Karzai returned to Kabul, the Afghan government furiously downplayed the demands Karzai had made. His enemies were quick to use the occasion, however. Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, one of the most powerful insurgent leaders, assailed Karzai for having come home empty handed.

“This agreement shows that the invasion of Afghanistan by the U.S. forces was not meant to remove the Taliban regime or eliminate al-Qaida but to have permanent bases here,” he said, echoing the complaints of many of the protesters. “We have always told people that Americans will have to be forced to leave this country; otherwise they will [follow through on their] plans to stay here for a long time.”

American military forces thought they would be mopping up people like Hekmatyar at this point, but springtime has opened up the snowy mountain roads used by insurgents. While coalition officials say they’re getting more help from the Afghan population and the newly trained Afghan army, attacks on U.S. and Afghan government forces are more frequent now than they were a year ago. On Wednesday, a suicide bomber killed 20 mourners at the funeral of a pro-government sheik.

Still, Afghanistan has not yet turned into Iraq. Most of its warlords are not joining the insurgency; rather, they’re trying to co-opt themselves into the government at the highest possible price. Compared with the alternative, that’s fine by the United States. After all, as one Western diplomat said, the end of the honeymoon doesn’t mean that the relationship is over. It just means both parties have a more realistic idea of what they’ve gotten themselves into.