“Proof” isn’t just a movie about mathematics; it’s a mathematical movie. The scenes may as well have been laid out by diagram: Let’s put a touching father-daughter moment here, a startling revelation there, and use interstitial flashbacks to cube the total emotional-resonance quotient.

Occasionally, Gwyneth Paltrow, as Catherine, the depressed daughter of mad mathematical genius Robert (Anthony Hopkins), shuffles onto the porch of the family house, the stereotypical academic shambles furnished mostly with stacks of books and unwashed dishes. There, she hunches into a fetal heap, finding temporary relief from oppressive dust motes. She has cared for her father for many of the last years of his life; now he has died, and she doesn’t know what to do — her future has become “x,” and we’ll need to sit through every one of the movie’s endless calculations to determine that elusive value.

“Proof” was directed by English stage and film director John Madden (“Shakespeare in Love”), and based on the much-lauded, Pulitzer Prize-winning play by David Auburn (who, along with Rebecca Miller, adapted it for the screen). Those who didn’t see the theatrical production (myself among them) might be left wondering if the material looked this phony on stage. This “Proof” is allegedly deep and thought-provoking, but it’s really no more than a dry, arty reworking of that whiskery old chestnut, the “What’s the line between genius and madness?” melodrama. Classical musicians and artists are usually the victims of these dreary treatments, but mathematicians, à la John Nash, are sitting targets, too. This time we get one who made great strides in his field in his early 20s before starting to skid down that slippery slope.

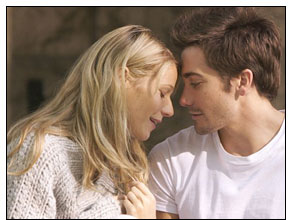

But “Proof” focuses more on Catherine and the stress she suffers while she cares for her father and immediately after he dies. In his later years, Robert became a compulsive writer — “like a monkey at a typewriter” is how Catherine wryly describes him — scribbling down nonsense in a series of notebooks (103 of them, to be exact). Hal (Jake Gyllenhaal), one of Robert’s former students, has been sifting through this weedy tangle of gibberish, hoping that Robert, in one of his brief moments of lucidity, will have jotted down something brilliant that he can present — in Robert’s name, of course — to the world.

But Catherine is a mathematician too. Her education has been sidelined in the years she has spent caring for her father, but that doesn’t mean she hasn’t been working. And she too may be brilliant — but she may also be crazy, as her buttoned-up nongenius sister, Claire (Hope Davis), who flies back to the Chicago homestead from New York just to say dumb, insensitive things (every story needs a scapegoat), seems to think.

Catherine just can’t get a break: She shares an intimate evening with Hal, but the next day, after she makes a startling confession to him, he essentially asserts that she can’t possibly be good at math ’cause she’s a girl. There are some vaguely interesting ideas floating around in “Proof,” particularly regarding sexism in scientific and mathematical fields. (Lawrence Summers might like to have a look at it.) Yet the picture, as carefully made as it is, feels as substantial as cardboard. Madden directed “Proof” on the London stage, with Paltrow in the lead role. But it isn’t a role that suits her, and not because she isn’t an intelligent, able actress. Paltrow has done some terrific work, often in unfairly maligned movies (like Neil LaBute’s craggily romantic “Possession” and Alfonso Cuarón’s erotic fever dream “Great Expectations”). It’s when she works hard to prove her seriousness that she stumbles. Her voice, with its reedy, nasal quiver, is her greatest liability — when she doesn’t keep careful control over it, she has the intonation of a bored, lazy middle-school girl. And her Catherine may be pouty and whiny for some very good reasons, but you can’t build much of a performance out of schlepping around in sweat pants and lumpy cardigans, which is what Paltrow spends most of her time doing here.

Hopkins has far less screen time than Paltrow does, although there are a few affecting moments between the two of them: At one point he impulsively leans forward to touch her forehead with his, a small gesture that says a great deal about the ways seemingly undemonstrative parents show love for their children. Gyllenhaal, another actor who has done fine work elsewhere, is wearying as a Peter Pan academic — enough with the winsome puppy eyes, already. And Davis, sometimes a marvelous actress but too often made to seem drippy and drab, tries to add some gentle shading to her role here, but little of it sticks. She’s the movie’s necessary bad guy, Catherine’s exact opposite in chic, clickety-clacking high heels and a perky raspberry-pink coat.

There are scenes in “Proof” that stretch the bounds of believability just to score feeble points (including a post-funeral gathering that looks and sounds like a tony cocktail party, the better to heighten the disparity between the “seriousness” of Robert and Catherine’s interior life and the cheap, glitzy outside world).

And then there’s the dialogue, like this precoital gem from Catherine, which she utters just as she and Hal are finally getting down to business: “I feel like I could crack open, like — an egg, or one of those really smelly French cheeses that ooze when you cut them.” In a director’s statement included with the press notes, Madden explains that the “film explores a mystery whose solution lies somewhere between the certainties of mathematics and the shifting perspectives of human experience.” But nowhere does he warn us about the cutting of the cheese.