More than virtually any other celebrity of any caliber, Harvey Pekar is famous for being nobody in particular. He's lived in Cleveland all his life; he worked as a file clerk at a V.A. hospital for decades, and read a lot, and listened to jazz records, and wrote about them for pin money. His life wasn't fascinating by the usual standards; his stroke of genius was deciding to document it anyway, in comic-book form. "Why [can't] comics be about the lives of working stiffs?" he asks in his new book, "The Quitter." "We're as interesting and funny as anyone else." Pekar started writing as if his resentment about washing dishes was something the rest of the world should be interested in -- and eventually they did start paying attention.

Pekar started publishing his autobiographical comics series "American Splendor" in 1976, and it's appeared in one form or another almost every year since then. From the get-go, it featured a bunch of cartoonists' visual interpretations of Pekar's scripts -- most famously Robert Crumb, an old friend of his whose presence in the early issues made readers take notice.

At first, "American Splendor" rarely showed anything like a significant moment in Pekar's life. Instead, he focused on relentlessly quotidian incidents and conversations: interactions with co-workers, domestic non-events, chatter about his name. The series was startling for what it "wasn't" -- in the mid-'70s, basically the only other American comics were mainstream pulp adventure and sex-and-drugs-obsessed "undergrounds."

But what "American Splendor" was was pretty fascinating too: a refracted memoir, focusing on the ordinary and valorizing it over the extraordinary. Every few pages, readers saw a different artist's interpretation of Pekar's words, in a way that broke the illusion that the only person telling the story was the person it had happened to. Pekar made memoir-comics possible, although it took a string of gifted writer-artists to make them fashionable. By the late '80s, a wave of autobiographical and semiautobiographical comics had begun in the wake of "American Splendor," and it's kept going ever since: Chester Brown's "The Playboy" and "I Never Liked You," David B.'s "Epileptic," Marjane Satrapi's "Persepolis," Ed Brubaker's "Lowlife," and dozens of others.

Meanwhile, in the mid-'80s, Pekar started appearing on David Letterman's show, and his interactions with Letterman naturally started showing up in "American Splendor." He eventually got banned from the show (for wearing an "On Strike Against NBC" T-shirt) -- a story that was told in the comic too. When Pekar fought lymphoma in the early '90s, he and his wife, Joyce Brabner, turned their experience into the script for a graphic novel, "Our Cancer Year"; when the 2003 "American Splendor" film about his life became an indie hit, Pekar responded with another book, "Our Movie Year." But it's hard to write about life outside the spotlight when the spotlight has moved onto you.

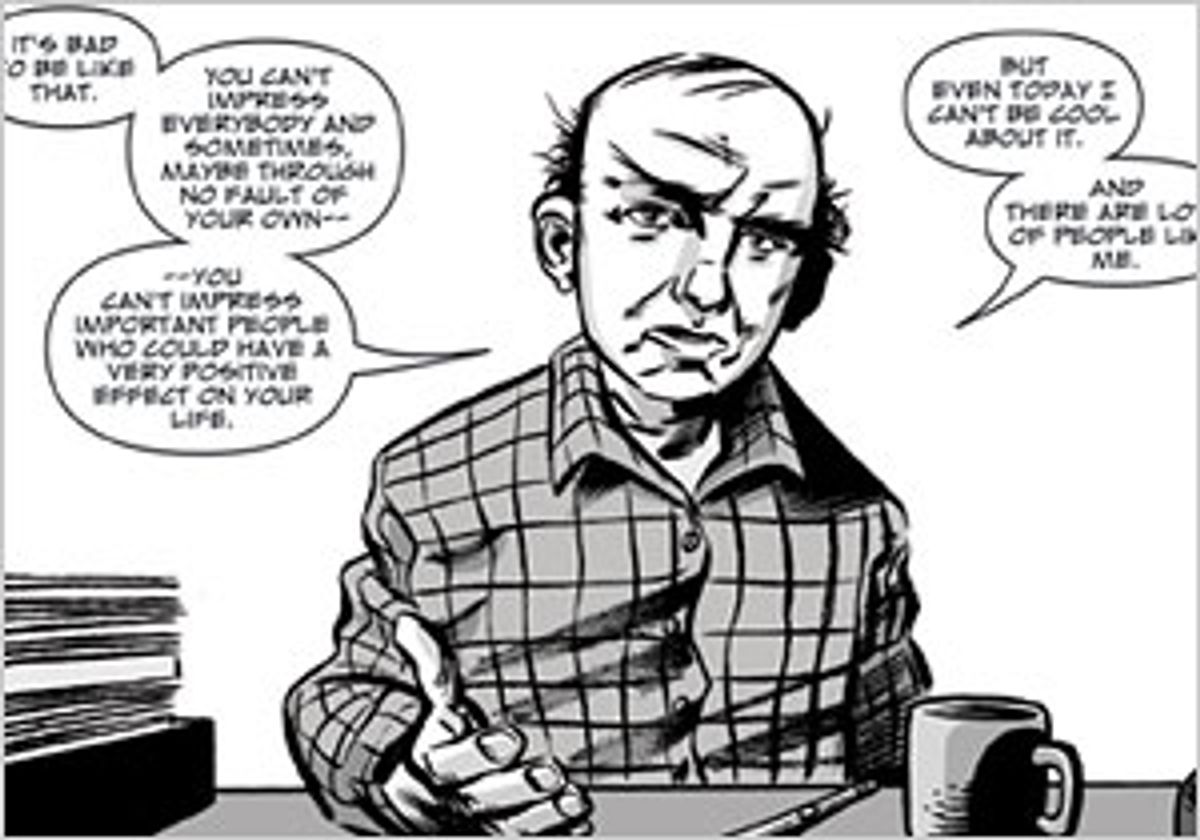

So "The Quitter," drawn by Dean Haspiel from Pekar's script, covers territory he's only dealt with glancingly before: the years before he started writing "American Splendor." It's narrated in the same mock-conversational first-person style Pekar usually adopts, with "yeah" and "let me tell you" and "anyway" everywhere, but this time the scope of his story is far wider than he's ever attempted in the past.

At first, "The Quitter" looks like it's going to be about Pekar's street-fighting career, or his habit in his early years of giving up on anything he couldn't immediately master. Young Harvey -- or, as his Polish immigrant father calls him in Yiddish, Herschel -- gets in fights with groups of kids in his mostly black neighborhood (Haspiel draws the scuffles in Dynamic Superhero Comic Book style, with limbs flying everywhere and nobody's feet on the ground); then he moves to another neighborhood, wins a couple of one-on-one fights, gets involved in sports and has his bar mitzvah.

Next, he gives up on sports after he doesn't make the starting football team, can't find a better job than working in his family's store ("It never even had a name. There was an ancient Salada tea sign on one of the windows, but no name"), and decides to redirect his energy into making a name for himself by beating up other kids. A little later, he discovers his lifelong fondness for jazz, then tries file clerking for the first time.

If this sounds like somebody recounting an incoherent dream -- "and then I, and then I" -- that's the tone of "The Quitter": a rambling series of events that don't often seem to belong together. Pekar's got a remarkable memory for details, recalling his fascination with a bout between Sugar Ray Robinson and Artie Levine or a coach's insult in eighth-grade football, but he jumps from one anecdote to the next as if he's racing toward a payoff that never arrives.

After some more notes on Pekar's late high-school life, "The Quitter" moves on to the first incident that's compelling as more than background information. In 1957, 17-year-old Harvey joins the Navy; a week into basic training, he has some sort of mental breakdown when he can't figure out how to wash his laundry, and gets discharged. The whole thing's over in little more than five pages, and back we go to the string of anecdotes: He tries a few more jobs, goes to college, listens to music, hitchhikes to New York, moves back to Cleveland, starts writing jazz criticism, has a few more fights, and on and on.

Eventually, there's a climax of sorts when Harvey gets into a fight with his father and cousin, and ends up belting his cousin in the face. Again, it's drawn to look like a big action scene: The punch gets a full-page panel, with an exploding halo around the cousin's upper body. But it doesn't have the dramatic impact it's supposed to -- in the context of the story, it seems weirdly melodramatic and overstated. And it's followed by another 20-page series of incidents to wrap up the book, in which the themes of Pekar-as-quitter and Pekar-as-fighter are all but abandoned.

Three pages before the end of the story, our man finally has his epiphany: He'll write a comic book. "Boy, I wonder why no one's tried anything more ambitious with comics before," Pekar shows himself thinking as he looks at an issue of Gilbert Shelton's underground dope-humor comic book "The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers." "They're such a great medium." This is what's known as preaching to the choir -- preaching about oneself to the choir, actually -- and it doesn't help that he follows it by pointing out that he's still really insecure and requires praise for his work.

It's an open question, though, why "The Quitter" is a comic book at all, as opposed to a brief prose piece. A lot of what's great about the comics medium is that it makes it easy to show the reader things instead of telling. But Pekar is constantly telling us what's going on with chattering captions -- and sometimes telling us some more, with redundant expository dialogue that lacks the grace of "American Splendor's" carefully observed conversational rhythms. One "Quitter" panel's caption, for instance, describes how Pekar was happy to be corresponding with jazz critic Ira Gitler; the image below it shows the young Pekar, leaning on a mailbox and holding a letter, saying, "Oh, man! Another letter from Ira Gitler. Great! They're so substantive."

If only that were true of "The Quitter." What's missing from it is the thing that made Pekar's early comics so much fun: their keen, witty observations of what people do and say when there's really nothing much going on. Frustratingly, though, he keeps hinting at his ability to evoke those moments. In one promising scene, he introduces us to a handful of the guys he hung out with in high school -- and then we never see them again. All we see of their conversation is "So then I said..." "That's telling 'im!"

Fortunately, Haspiel's artwork gives the book a much-needed sense of continuity. He's got a real feeling for Pekar's work -- his own comic "Opposable Thumbs" was part of the post-"Splendor" autobiographical stream -- and his boldly stylized, cartoony brushwork keeps the narrative rolling. Haspiel's Pekar is believably schlubby, always reclining against something or slumped forward at a 30-degree angle, and occasionally there's a lovely visual gesture: On one double-page spread, for instance, teenage Harvey, beaming over a fistfight victory, is mirrored on the opposite page in the same pose as a haunted 65-year-old, wondering "how I'm going to get by the next several years."

He's pretty clearly hoping that his comics will do it -- on the final page, Pekar's looking at a contract for ... "The Quitter." Ultimately, that's what the book is actually about: It's the memoir of an autobiographer, the story of how he came to write the story of his life. The education of an artist is a familiar theme for a memoir, but it seems slightly inappropriate for Pekar: It requires a presupposition that the person relating his life is somehow extraordinary, an idea that's at odds with Pekar's I'm-just-another-normal-guy stance. And the problem is that his early years don't make for a fascinating story -- at least not in this sweeping, rambling mode. He's so busy mentioning every event of consequence in his life that he glosses over the non-events that mean much more in his work.

Shares