If you strive to love your neighbor as yourself, then God calls you to join the fight against global warming. That’s the message that a group of 86 evangelical leaders, dubbed the Evangelical Climate Initiative, preached at a press conference in Washington Wednesday, quoting scripture and calling on Congress and the White House to pass national CO2-emission reductions.

But the spirited call to action took place without the blessing of the largest evangelical group in the country, the National Association of Evangelicals, whose members represent 30 million of the faithful. Powerful, politically connected evangelical leaders like James Dobson of Focus on the Family prefer not to take a stance on global warming and had requested that the association follow their lead.

The schism among evangelicals reflects political tensions in their relationship to the White House. Some who side with the Bush administration’s do-nothing policies on global warming even pressured sympathetic evangelical leaders not to speak out, in a strategy that mirrors the one the White House has used to stifle science it disagrees with. So the splinter group of principled preachers is striking out on its own, taking on the biggest environmental threat God’s creation has ever seen.

Declaring that human-induced climate change is real, and that its likely impact on the world’s poor requires Christians to take action, the statement was signed by dozens of pastors, including the author of “The Purpose-Driven Life,” Rev. Rick Warren, as well as Christian college presidents and Christian relief organization directors.

Among their ranks is Duane Litfin, president of Wheaton College (whose most famous alum is Billy Graham). Litfin says that the people who will suffer most from climate change will be the poor, vulnerable and marginalized, as their sources of water, air and food production are threatened.

“What is required of a Christian when you see those kinds of issues on the table?” he implored at Wednesday’s press conference. “We have a major set of convictions about coming alongside a neighbor who is in desperate need. This isn’t someone else’s issue. This is our issue. Can we please step up?”

Todd Bassett, who serves as national commander of the Salvation Army, warned of the rise of national disasters around the world, recalling his recent visit to 10,000 families in Florida, who have been living in FEMA trailers for the last year and a half. And Leith Anderson, former president of the National Association of Evangelicals and a pastor in Minnesota, quoted St. Peter and declared: “Those 86 of us who have signed this statement and others as well, we’re doing what is right, and we’re not afraid.”

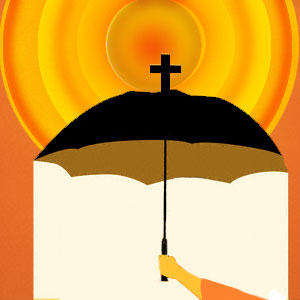

Fearlessly disregarding the wishes of message-makers like Dobson is a bold gesture, and the ECI signatories don’t intend to hide their light under a bushel: They’re running print ads in the New York Times, Roll Call and Christianity Today, as well as TV ads on Fox News and ABC Family, aiming to educate the evangelical flock about the threat of global warming to God’s creation and inspire them to action. The signatories will spend the coming year preaching about the dangers of climate change at Christian universities and in their own churches. And in November, the group will meet with businesses, including coal-burning utilities, to discuss strategies for reducing emissions.

Enviro-minded evangelicals say the campaign is the first step toward reaching skeptical Christians. “The statement is groundbreaking. It lays a foundation in our community for building a consensus on global warming,” said the Rev. Jim Ball, the executive director of the Evangelical Environmental Network, best-known for its “What Would Jesus Drive?” campaign.

Still, while climatologists have reached consensus on global warming, it’s clear that evangelical Christians have not — at least not yet. There were two important names not on the list of luminaries signing on to the ECI statement: National Association of Evangelicals president Ted Haggard and vice president of governmental affairs Richard Cizik. Despite the fact that both men personally agree with the ECI’s tenets and goals, Haggard and Cizik did not sign the declaration for fear that the NAE would be seen as endorsing it.

In June of 2004, Haggard and Cizik indicated their commitment to what Christians call “creation care” issues by signing the Sandy Cove Covenant, a declaration of intent to create a consensus statement on human-induced climate change among evangelicals. But since then, climate skeptics within the NAE have clamped down.

Last month, the NAE came under pressure not to take a position on global warming from its most conservative members, including James Dobson and Oral Roberts University president Richard Roberts. The Interfaith Stewardship Alliance sent a letter signed by Dobson, Roberts and 20 others leaders declaring that “We are evangelicals, and we care about God’s creation. However, we believe there should be room for Bible-believing evangelicals to disagree about the cause, severity and solutions to the global warming issue.”

Calvin Beisner, an associate professor of historical theology and social ethics at Knox Theological Seminary, who was one of the signers and authors of that letter, says that many evangelicals continue to have serious doubts about global warming. “Such a policy of mandatory CO2 emissions reductions as a means of combating global warming rests on three major assumptions, all of which we think are debatable, if not downright false,” he said.

The assumptions that Beisner sees as debatable are that global warming will have catastrophic effects, human emissions of CO2 are a large enough part of the problem that reducing them could significantly reduce global warming, and mandatory emission reductions would have more beneficial than harmful effects on the global environment and human economy.

However, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the world’s leading scientific body on global warming, which includes evangelical Sir John Houghton, doesn’t view the points as debatable at all.

Calvin B. Dewitt, a professor of environmental studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who is also evangelical, compared the silencing of Rev. Richard Cizik on climate change to the recent muzzling of Dr. James Hansen at NASA. “Here is a person who has not changed [his position], he is just being silenced. People are asking what kind of truth-seeking this is, when a person who is a principal leader in bringing an awareness of climate change to the whole evangelical world — what is going on that’s compelling the NAE executive committee to say you cannot speak for us?” Dewitt predicted that the tactic would backfire on the NAE, since evangelicals have an ideological distaste for church hierarchy, dating back to the Reformation: “It’s raising the issue even higher than it was before.”

And in spite of scientific skepticism from evangelical leaders, many in the community seem well aware of the issue. The Evangelical Climate Initiative cites a poll that the group commissioned of 1,000 evangelicals, which found that two-thirds believe global warming is taking place, and seven out of 10 believe global climate change will pose a serious threat to future generations.

Melanie Griffin, director of environmental partnerships for the Sierra Club, who is an elder in her evangelical church in Spencerville, Md., says that she believes the grass roots are in fact ahead of their national leadership on climate change: “I think it’s growing pains. It seems to be what is going on.” She says that after spending a decade working on environmental issues with church groups, she’s seen an explosion of interest from local congregations and youth groups in the last two years. “The local churches and individual evangelicals are getting really engaged in creation care, and some of the national spokespeople are coming on a little more slowly.”

Sally Bingham, an Episcopal priest who is the environmental minister at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, is not surprised that evangelicals have not yet come to a consensus on global warming. Bingham, who runs a religious effort on global warming in 17 states called the Regeneration Project, says that evangelical children are taught not to trust scientists as soon as they enter Sunday school, starting with resisting the theory of evolution: “Why would evangelicals believe what the scientific community is saying now about global warming when they were raised as children to be suspicious of science?” But she believes that the evangelicals who do believe in global warming and are committed to doing something about it will ultimately prevail: “I believe that the evangelicals will move forward on a consensus on climate change. I don’t think that the voices that understand the science are going to go away. Eventually, the scientific evidence will be so overpowering the evangelicals will come onboard.”