A couple of weeks before the 2004 American presidential election, I checked out of a hotel in central Tehran in order to check into a friendlier one around the corner. The first was a towering block of featureless rooms, its lobby forever crowded with bored, shabby men who may or may not have worked there. Two men staffed the reception desk, and they seemed to track my every movement, whether out of professional obligation or to amuse themselves wasn't clear. An Iranian friend who called for me complained that they gruffly questioned her: Who are you? What is your father's name? Who is the American? How do you know her?

So it was that I stood impatiently before the window to check out while the receptionist took his sweet time to retrieve my American passport from the cubby behind him. He held it for a long, strange moment before he slid it my way.

Wistfully, he said: "How I wish I had a passport like that."

Off we were, talking about the election. The receptionist hoped President George W. Bush would defeat Sen. John Kerry. He hated the Democrats, he professed. It wasn't my first encounter with this Iranian enthusiasm for the Republican Party, as unfathomable as it was widespread. Under the Republican President Dwight Eisenhower, after all, the United States toppled Iran's popular nationalist prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, in 1953, consolidating power in the hands of the brutal and despised shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Under the Democratic President Bill Clinton, the United States finally apologized for engineering those events. I asked the receptionist to explain.

"Jimmy Carter," he replied with disgust. "He could have stopped this Islamic Revolution, and he didn't."

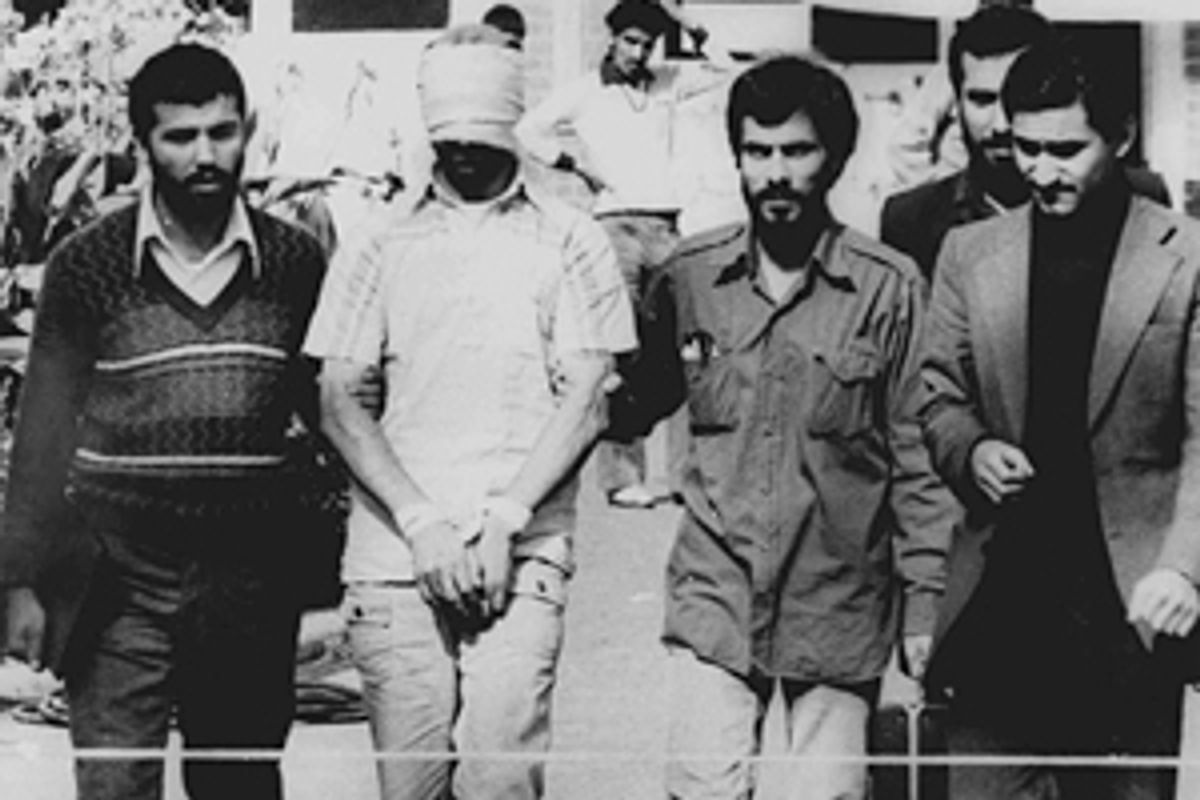

When it comes to Iran, where revolutionaries identified Carter with every bad turn the United States had ever visited on their or any other third-world country, and where Americans would come to associate him with haplessness and defeat, somehow everything the president from Plains, Ga., did would always be wrong. His presidency, already a fragile vessel, shattered on the shoals of the Iranian hostage crisis -- those 444 days at the end of his single term when the staff of the American embassy in Tehran was held captive by militant students. From then on, he would forever be linked in the American mind with the humiliation of seeing one's countrymen blindfolded, helpless, surrounded by angry mobs of Shiites -- believers in a religion most Americans only dimly apprehended, revolutionaries who hated the United States for having supported a regime most Americans were barely conscious existed. And now, 26 years later, this Iranian hotel worker in a single gesture renounced his country's revolution and laid it at the feet of the very president whose likeness Iranian revolutionaries burned in effigy as they massed outside the seized embassy compound. It's been a long quarter-century in Iran.

In "Guests of the Ayatollah: The First Battle in America's War With Militant Islam," Mark Bowden, the celebrated author of "Black Hawk Down," takes us back to the Iran of 1979 and the America of the Carter White House, painstakingly recounting the 444 days of the Iranian hostage crisis. It is an uneven but riveting book -- history written as thriller, a suspenseful narration of one of the more bizarre and dramatic episodes in the annals of American diplomacy. It is doggedly reported, reconstructed with a detective's eye for detail, and strangely, given the times, only tenuously tied to any larger frame of meaning.

The story opens on Nov. 4, 1979, when Bowden's sweeping cast of characters reported for an ordinary day of work at the American embassy in Iran's unstable capital. "Ordinary" was a relative term in the nine months after the fall of the shah; the embassy's staff, nearly all of which had turned over since the revolution, was wholly aware that the buildings might be laid siege. Students had already attempted to take the compound in February and been expelled. But when President Carter admitted the ailing, exiled shah to the United States for medical treatment, despite ample warning that doing so would leave the American embassy staff vulnerable to reprisals, many of the diplomats regarded the demonstrators outside their compound with mounting apprehension.

Students poured over the walls that isolated the embassy compound from the city, encircling the buildings and heading straight for the least secure openings, which they'd evidently scoped out earlier. The Americans executed a plan the embassy's Marine security force had devised after the February attack: They were to barricade themselves on the second floor of the chancery, and if that redoubt were breached, they'd retreat to the vault on the same floor, where they had reserves of food and water. Although the Marines were well armed, under no circumstances were they to shoot at Iranian interlopers. Anti-American fear and suspicion were so powerful in the Iranian capital that to open fire might ignite a spiral of violence. As a last resort, the embassy guards could lob tear gas grenades.

Bowden seems to have debriefed nearly every living hostage for untold hours, and he recounts the embassy siege with a battle historian's zeal for minutiae. We know exactly who was where, doing what in what order. The Iranian students put a gun to the security chief's head and threatened to shoot if the diplomats didn't admit them to the second floor of the chancery. A small coterie of embassy staff members retreated to the vault, hastily destroying as many sensitive documents as they could find. Communications specialist Rick Kupke noticed that all the embassy's firearms had also been loaded into the vault and worried that if he and his colleagues were found there with a cache of weapons, they would come under fire. So he crept up through a hatch onto the roof with armfuls of firearms, looking for places to hide them. When the Iranians breached the vault, Kupke hesitated on the roof: Should he surrender himself or risk being found, surrounded by weapons?

In the end all of the Americans surrendered. Those suspected of being CIA were threatened or beaten; so were those suspected of knowing the combinations to various office safes. The day finished with many of the American diplomats and Marines tied to chairs in the ambassador's residence. From there, we follow the hostages' movements from one part of the compound to another, through an array of holiday pageants and propaganda interviews staged for the Iranian and foreign press, and eventually into the Tehran prison system, where they were held following a brief dispersal to various Iranian cities after a botched American rescue attempt. We hear their thoughts, their most banal memories of captivity, their captors and each other; we follow the overgrowth of their hair and beards, their weight loss, the deterioration of their clothes, which some learn to wash by stepping into the shower fully dressed; we witness the humiliation of being issued too-small underwear.

At the book's lesser moments, this thicket of detail can try a reader's patience. We learn that on the day of the embassy's seizure, the security chief, Al Golacinski, pulled on his cammies in a hurry and thought they looked ridiculous with his loafers; we learn that a political officer, John Limbert, was preoccupied with his need for a haircut. Near the end of the first 24 hours' ordeal (recounted in some 180 of the book's 680 pages), we learn that one hostage's "butt hurt from sitting in the same position for so long." Are we to conclude that if any one of these facts had been otherwise, things might have worked out differently? Or is it simply the odd trivia that has been emblazoned on the memories of the captives, such that 26 years later, they still think to tell a reporter how they felt that day about their shoes? One waits in vain for the significance to reveal itself; the details are recounted with a historian's detachment but a novelist's unfulfilled promise of resonance.

A little character development helps, and though it's often hard to keep the 66 hostages straight, we manage to follow an impressive array of experiences over the sweep of Bowden's tale. From the consulate, we get to know Richard Queen, who begins to suffer from a mysterious, frightening, degenerative illness in captivity. (Irritatingly, after building the reader's concern and sympathy for Queen over hundreds of pages, Bowden never reveals what it was that ailed the vice consul; for those who wonder, it's multiple sclerosis.) Bruce Laingen, the embassy's chargé d'affaires, was the top American diplomat in Tehran following the revolution (no new American ambassador had yet been installed). On the day of the hostage-taking, Laingen had an appointment with the foreign minister, which he attended with one political officer, Vic Tomseth, and a Marine security guard, Michael Howland.

The three of them would become unofficial prisoners at the foreign ministry for the duration of the crisis, confined to an incongruously grand dining room that crawled with cockroaches after dark. If they left the ministry, they would fall into the hands of a waiting mob; if they sought refuge in allied embassies, they would expose those embassies to violence. At the foreign ministry, they tried fruitlessly to negotiate their own and their colleagues' release. They read their way through the ministry's library, occasionally making their bedraggled presence known to visiting dignitaries; Howland made mischief by disabling the guards' weapons on the pretense of teaching them how to disassemble and maintain them and by prowling the ministry naked at night. Laingen kept a diary in which he could remain a statesman, recording political observations and reflections even as he felt himself fading to irrelevance as anything but a hostage.

The rest of the Americans were confined in various parts of the embassy compound, some in the notorious "Mushroom Inn," as they dubbed a moist basement of cell-like cubicles. The interrogators and guards, too, got nicknames: Gap tooth, Hamid the Liar, Queenie, Bozo. Some of the hostages suffered mainly from confinement and boredom; others seethed with anger; still others were regularly beaten and interrogated. One of the book's most oddly interesting passages details how each prisoner passed the long hours. One taught seminars on constitutional law in his head. Another painstakingly remodeled his family's home in his mind's eye. Yet another organized a library for all the hostages to use. Still another found God. Most attempted to exercise by doing calisthenics or running in place. Those who shared spaces tried to beautify their temporary homes. Those without roommates communicated with one another furtively, leaving notes in shared bathrooms or squeezing them into openings in the walls.

The embassy's two top political officers were a study in contrasts. Mild-mannered John Limbert was the quintessential diplomat, conscious that his captors were very like the Iranian students he'd taught in Shiraz, forever seeking reasonable common ground. Michael Metrinko had been hard-drinking, chain-smoking, always a step ahead of his colleagues in local knowledge that he swiftly soaked up during long, late nights on the town and through an impressive network of well-connected insiders. He knew and loved Iranian culture and politics perhaps the best of anyone, and he would prove to be the most recalcitrant and worst treated of the captives. He never missed an opportunity to insult his jailers, something he could do floridly in Farsi; perhaps the only thing that gave him pleasure was to spite them, even if it meant rejecting a mouthwatering Christmas meal they delivered to him and which he desperately wanted to eat, or quitting his two-pack-a-day smoking habit cold turkey rather than accept a cigarette. Metrinko was viciously beaten and kept in solitary confinement for more than a year.

The Iranian captors, seen through the eyes of their hostages, remain cartoonish figures in Bowden's telling. They are ill-educated, conspiracy-minded, cultish and cruel. They reportedly saw Americans as omnipotent and malevolent spies, whose very watches and wedding rings contained secret chips that allowed them to communicate with Washington. Bowden depicts them as pious bores, sincere believers in their revolution's power to remake the world in the interests of its oppressed and in the image of their faith. To the militants' vision of an all-seeing, all-powerful America, Bowden counterposes a CIA presence of three operatives, all new to their jobs, not one of whom spoke Farsi or ran a single useful agent in a country whose revolution had rendered it terra incognita. To the militants' provincialism and starry-eyed utopianism, he counterposes an embassy staff of jaded and worldly foreign service bureaucrats, forced to listen to tiresome lectures about the coming betterment of the world.

From the point of view of the hostages, it was an absurd encounter, a case of mistaken identity. These were not even the same diplomats who staffed the American embassy under the reign of the shah; and though the Iranians claimed that the CIA sought to reverse the Islamic revolution, the Americans believed that their mission was to convince the Iranians that the United States accepted their new government, as well as to find a few friendly informants who might make the Islamic Republic's inner workings less opaque. To the Americans, the hostage-taking was an unthinkable act of thuggery, inspired by collective delusion. To the Iranians, it was a triumphant invasion of a "den of spies." The students maintained that they had not kidnapped a diplomatic mission so much as arrested a hive of scheming foreign subversives. At first Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini equivocated over the hostage-taking; when he endorsed it, moderate Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan and his interim government resigned, leaving Washington without a real negotiating partner.

Never had the rules of international statesmanship been so manifestly and dramatically abrogated; and yet the world chose not to censure Iran, and the United States looked on helplessly. As Bowden depicts him, Carter was a deliberate leader, driven not by political calculation so much as by agonizing moral and strategic judgment. He feared that any hostile move would lead the hostages to be executed and could touch off a larger conflagration in a contested region on the Cold War battleground. But refraining from action cost the United States and its president dearly on the world stage as well as in domestic politics. The Carter administration undertook back-channel negotiations again and again. Each time, they foundered on Iranian factionalism, but to the outside world it simply appeared that the Iranians had wrung humiliating concessions from Washington and then failed to deliver the hostages.

Finally, Carter agreed to launch a rescue mission, using the recently founded Delta force, which specialized in highly skilled and secretive military operations. Bowden's reporting on the rescue attempt is a tour de force. As a last-ditch effort, the United States military had grimly undertaken an operation with an unthinkably low probability of success -- a leanly manned excursion into the heart of a hostile country, where many of the Delta force men were prepared to sacrifice themselves. The result was not just loss of American life, but yet another embarrassment before the eyes of Iranian militants and the world. It was not enough that the secret mission failed: It failed in a spectacular explosion that lit up Iran's night sky and killed eight American military men.

Here Bowden's cinematic detail pays off. When two agents scoping out the desert meeting point for American aircraft hear a truck on the nearby highway, they sprawl on the ground. Bowden knows what song one man sang to the other at that moment. He knows what the inside of an airplane smelled like as it perilously wove through Iranian airspace, avoiding the radar system the Americans knew because they had sold it to the shah. An incredible story unfolds in that desert in the dead of night. A bus of passing Iranian pilgrims was briefly held hostage, for fear the passengers would report the unmistakable presence of two American planes and six helicopters in a patch of desert off the road. The plan was to fly the bus passengers to Egypt until the rescue operation was complete. But the operation failed, in part because it was stunningly audacious; in part due to internecine battles and volatile leadership; and mainly because those who painstakingly planned the mission did not account for anomalous desert weather conditions that proved fatal to the helicopters. Bowden's exhaustive reporting and fast-paced story-telling render to history an episode all but blocked out of American memory.

Bowden's book is a page-turner, but its final chapters do not do justice to the epic story he has gone to great trouble to reconstruct. He has narrated the events of those 444 days from a bird's-eye view, without interview quotes or attribution, but hewing closely to the experiences of each of the story's great many characters. It's an absorbing and effective technique -- until it abruptly ends after the hostages board the plane that will take them to freedom. Then we get a chapter that tells us what became of each hostage in what feels like a brisk run-through of their résumés, one piled atop another.

Bowden then travels to Tehran, which, by his description, is colorless, dirty, smelly, bland and desolate, scarred by ugly architecture and choked with traffic -- a suffocating place where nothing grows and Allah forbids every hue but Islamic green. It's a superficial impression, guided by preconception, and not a surprising one from someone who has clearly spent countless hours immersed in the bitter memories of the hostages. But since he has gone to the trouble to take us back to Iran, one wishes Bowden evinced more feeling for the density and variegation of contemporary Iranian life, for its contradictions and lyricism, for the sophistication and dignity of its intellectual culture and politics, let alone the last decade's striving for reform, however stymied.

Bowden might have rendered some of the country's recent history through the hostage takers he went to see in Tehran. Instead, we get a catalog of their whereabouts and long, undigested quotes from their political diatribes. Some of the hostage takers have remained true to the hard line they championed in 1979, while others became leaders of the movement for incremental reform. But we don't get much narrative or political context for these currents. Bowden has gone to the hostage takers essentially looking for a renunciation of the embassy takeover, which has become one of the founding myths of the Islamic Republic; and he only passingly acknowledges that "perhaps" this mea culpa might not be forthcoming in a country where dissidents are routinely jailed and tortured. (He has even told us that he traveled under the auspices of an Iranian agency that required him to turn over tapes of all his interviews before departing the country.)

What exactly is the significance of the hostage crisis today? Why, in the year 2006, as tensions mount between the United States and Iran, should we return to that fateful moment in the history of our relations, and what will be illuminated there?

The obvious answers are unsatisfying, and Bowden doesn't really get us beyond them. His subtitle asserts that the hostage crisis was "America's first encounter with militant Islam." But then we are left to wonder exactly what this encounter touched off, and how, as well as what it might tell us about later encounters. Bowden informs us that militant Islamism is a traditionalist backlash against modernity -- the "death throes of an ancient way of life." The Iranian example, he writes, presents a pattern for the future of Islamism everywhere: A "fanatical fringe" will seize on popular discontent, offering a vision of paradise but leading only to corrupt and ineffectual dictatorship that the people will grow to hate.

There is nothing ancient about the way of life Iran adopted after its revolution, which introduced an entirely new vision of the state onto the world scene. And Bowden's generalized musings on utopianism have little bearing on the American encounter with the hostage takers, let alone with militant Islam. Neither of these superficial arguments follows from the 600 preceding pages, which have addressed the Americans' experiences almost exclusively. Bowden hasn't really figured out what the significance might be of the events he recounts, and this thick tome threatens to float away without an anchor.

Reliving the hostage crisis outside any convincing matrix of meaning is sure to leave many American readers with nothing but outrage, especially considering that Iran's current president is an anti-American hardliner whose rhetoric harks back to 1979. At a time when some in American political circles are calling for military strikes against Iran, rekindling that anger without purpose or context hardly seems a service. Between the present moment and the one Bowden narrates, there is a facile and dangerous parallel at hand. To make it is to pass over the last quarter century of Iranian politics, which has witnessed a unique fermentation of Islamist rule and democratic yearnings. It is also to misrepresent the meaning of the 2005 presidential election in Iran. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad did not ride to power on a wave of popular enthusiasm; he did so on a wave of despair. Bowden writes that no reformist candidates were permitted to run in that election, but in fact there were three, by some counts four. Their constituency was divided, demoralized and angry. Ahmadinejad's ascendance reflected not a resurgence of revolutionary purism in Iran, but the political failure of the reform movement, as well as widespread frustration with economic hardship and government corruption. Iran remains, confoundingly, the country in the Muslim Middle East with the government most overtly hostile to American interests and the populace most open to democratic values. That's partly why Iran is such a puzzle for American policymakers, more now than in 1979.

Today, the former American embassy compound crouches behind a wall daubed with the revolutionary murals many young Tehranis have come to regard as the kitsch of their parents' youth. It is almost impossible to imagine American diplomats cruising through its gates and out into the clangorous Iranian capital. What might the world be like if they did? Bowden's book captures a precarious moment, a final point of contact between an Islamic Republic of Iran that was, in that instant, bloody and new; and a United States that was a world-weary Goliath, little suspecting that the world it had grown weary of was shifting beneath its feet.

Shares