At one point in Dustin Long’s endearingly wacky puzzle novel, “Icelander,” two “metaphysical detectives” discover a copy of “The Case of the Consternated Cossacks” on a bookshelf between Herman Melville’s “The Confidence Man” and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “Valley of Fear.” Since this bumbling pair, a kind of existential Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, see everything as a clue, they have no doubt that the book’s placement is significant, but as usual they just can’t figure out what the significance is. At this juncture, the novel’s “editor” intrudes. In a cranky footnote he observes that there would be equal meaning embedded in the fact that the books placed just above and under “The Case of the Consternated Cossacks” are by, say, Vladimir Nabokov and Elizabeth Peters (who, to the uninitiated, writes mystery novels about a sleuthing female Egyptologist). You see, the books have been shelved by “the most ingenious library scientist of modern times,” whose plan for a nonlinear “rhizomatic replacement of the Dewey Decimal System” entails sorting books without hierarchy, according to an “infinite skein of interconnections.”

“Icelander” itself could well occupy exactly the same spot in this system as “The Case of the Consternated Cossacks,” a book that doesn’t actually exist. Somewhere close at hand would also be one of Richard Russo’s wry novels about small-town life in rural New York. “Icelander” is set in New Crúiskeen, a college town in a state called New Uruk and the former home of Emily Bean-Ymirson, “an anthropologist by profession and a criminologist by birth.” Emily’s crime-solving exploits in the company of her husband, Jon Ymirson; her faithful dog, the Fenris dachshund, and various assorted friends and allies have been immortalized in a series of novels, based on her diaries, by Magnus Valison, “one of the 20th century’s master prose stylists.” (“Consternated Cossacks” is one of those novels.)

But by the time “Icelander” begins, Emily has been dead for years, and the once formidable Jon is suffering from Alzheimer’s. The protagonist of this novel is their daughter, known only as “Our Heroine,” a professor of Scandinavian studies at New Crúiskeen University. The action transpires over a few snowy days after Our Heroine learns that a close family friend, Shirley MacGuffin, has been murdered. Our Heroine strives mightily to hold onto the tragedy of her loss; she wants to avoid getting drawn into investigating the crime, something everyone else in town blithely expects her to do.

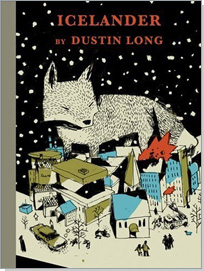

If you can’t already tell from the name of our murder victim that “Icelander” is a giddy sendup of postmodern fiction in all its referential frenzy, bear in mind that Magnus Valison, before writing his Emily Bean books, also produced two novels titled “Itallo” and “Ripe Leaf,” which if you work the anagrams pegs him as a Nabokov stand-in. Then there’s the Hollywood heartthrob and wannabe novelist, Nathan, who has come to town to celebrate Bean Day. And we haven’t even gotten to the Norse mythology yet, from the underground realm, Vanaheim, that Emily and Jon discovered in Iceland, to the shape-shifting fox warriors who can be glimpsed skulking all over town. Our Heroine was married to the hereditary prince of Vanaheim, but he has recently left her to return to his people.

Admittedly, this sort of thing isn’t for everyone — the very mention of a novel with footnotes has by now become enough to repel many readers. But the charm of “Icelander” lies in its refusal to take itself too seriously. Long plays the pomo game quite skillfully — one of Shirley’s literary projects is a “Two Story House,” a structure in which two different stories are written all over the walls and objects of the house, one story written on the first floor and the other on the second. But he never forgets that playing is exactly what all this is, and so he avoids the tedious solemnity with which so many metafictionists attempt to demonstrate their impishness. (Naturally, a dead body turns up in the Two Story House.)

Besides, at the heart of “Icelander” is a very believable woman who doesn’t want to be a detective, damn it. Our Heroine just wants to mourn her friend and her shattered marriage and to find her lost dog, the grandson of the Fenris dachshund. She’d like nothing better than to leave behind her former life (which involved such adventures as being kidnapped by an archvillain and rescuing her mother by bashing in a bad guy’s head with a stolen gold brick). “Icelander” is about her struggle not to be so fictional, and you can’t help but root for her, as secret passages and mysterious black limos confound her at every turn. On the other hand, you can’t help but root against her, since vengeful princesses and nefarious masters of disguise are pretty hard to resist from a reader’s perspective. Long obviously knows what it’s like to hover between wanting to read about underground kingdoms and purloined documents and wanting to read about just plain real people. In fact, he seems perfectly happy to keep on hovering there, and he knows how to make his readers happy there, too.