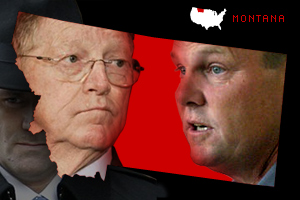

At a Sunday afternoon barbecue on the edge of town here, Sen. Conrad Burns wanted to talk about all of the federal money he can deliver for Montana residents and all of the ways in which his Democratic challenger will raise their taxes and leave them at the mercy of terrorists.

What he didn’t want to talk about was Jack Abramoff.

Burns took more money from Abramoff, his clients and associates than any other member of Congress, and press reports say he may be next in the sights of federal prosecutors who have already bagged plea agreements from Abramoff, two former aides to Tom DeLay, a former aide to Ohio Rep. Bob Ney and, most recently, Ney himself.

When a reporter put the Abramoff question to Burns at Sunday’s barbecue, the senator barked back: “Old news.” Burns said that he’s not a “target” in the Justice Department’s ongoing Abramoff probe. But when I asked him whether he falls into the category of potential “targets” federal prosecutors call “subjects,” Burns said, “I’m not a target.” I asked him again if he’s a “subject.” “I’m not a target,” he said again.

Burns spokesman Jason Klindt confirmed later that the Justice Department has told Burns’ criminal defense lawyer that he’s not a target. But when I asked Klindt whether Burns is a “subject” — described in the U.S. Attorney’s Manual as “a person whose conduct is within the scope” of a criminal investigation — he said he wouldn’t go beyond what he had just told me.

At the barbecue, another reporter asked Burns about the “tremendous amount” of Abramoff-related money he took. “I’m not talking about that situation,” he responded. “We’re going to talk about the future and what we can do for our state. I mean, all this has been a swirl out there, and nothing has happened.”

When I started to say that something has happened — that in Bob Ney, there’s now a member of Congress who has agreed to plead guilty in the case — Burns’ slow simmer hit full boil. “Now listen,” he snapped. “You guys are coming out of that 17 square miles of logic-free environment” — that’s what Burns calls Washington, D.C. — “and I’m not answering to you. I answer, I answer — my dialogue is with Jon Tester, who is my opponent. Period. End of conference. Thank you for coming.”

It wasn’t really the end of the impromptu press conference — another reporter cajoled Burns into talking about Iraq — and it almost certainly won’t be the end of the Abramoff questions Burns will have to face. The “culture of corruption” may have waned as a campaign theme for Democrats around the country, but it’s alive and well in Montana, where questions about the money Burns took from Abramoff — and the favors he may have done in return — have softened up the Republican incumbent for a challenge from Democrat Jon Tester. When a panelist raised the Abramoff question during a candidates’ debate in Butte Saturday night, Burns blew it off as nothing but “baseless allegations drummed up in a negative campaign.” Tester, meanwhile, said he’d never “sell Montana down the road by cutting deals with lobbyists like Jack Abramoff.” In an interview afterward, he told me that he expects Burns to continue “dodging” the issue until November because he doesn’t want to admit what he’s actually done. “The truth hurts,” Tester said. “That’s a fact.”

What’s the truth about Conrad Burns and Jack Abramoff? The basic facts aren’t really in dispute. Between 2001 and 2004, Abramoff, his clients and associates gave Burns nearly $150,000. In 2003, Burns tried to steer $3 million in federal funds intended for poor Native Americans to the casino-rich, Abramoff-represented Saginaw Chippewa tribe of Michigan instead. When Interior Department officials resisted, Burns delivered the money anyway via an earmark in a 2004 appropriations bill. There are also questions about an all-expenses-paid trip to the Super Bowl two Burns aides enjoyed courtesy of SunCruz, a Florida company partly owned by Abramoff, and about Burns’ effort to block legislation involving the Northern Marianas Islands that just happened to be opposed by two of Abramoff’s clients.

As the Abramoff story unfolded last December, an aide to Burns said the senator wouldn’t be returning any of the money from the disgraced lobbyist, his clients or associates. Then Burns switched course and gave the money back, saying that the contributions had “served to undermine the public’s confidence in its government.”

Returning the money may have helped Burns politically, but it’s not likely to have much of an impact on the opinion of federal prosecutors. Burns has long been mentioned as one of the lawmakers in whom Abramoff investigators are interested. Now, with Ney having agreed to plead guilty next month, Time says that investigators are paying “particular scrutiny” to the junior senator from Montana.

Abramoff has said that his staff and Burns’ staff were “as close as they could be,” that Burns’ aides “practically used” Abramoff’s Washington restaurant as their “cafeteria,” and that Abramoff and his clients got “every appropriation we wanted” from Burns’ committee. “It’s a little difficult for him to run from that record,” the former lobbyist said in a Vanity Fair interview published in March.

But when I asked Burns Sunday whether he’s completely comfortable with his relationship with Abramoff, he said: “I don’t have a relationship with Jack Abramoff.” He said it in the present tense, the same way Bill Clinton was able to say that it depends on what the meaning of “is” is. I asked Burns how many times he met with Abramoff. “Maybe once,” he said. What was the purpose of the meeting? “I don’t know because he was with a group of people,” he said.

The bottom line, Burns insists, is that the Abramoff story doesn’t matter and shouldn’t matter to voters in Montana. “What does that do for jobs in Butte, Montana?” he asked at Saturday night’s debate. In what seems like a fallback position — no harm, no foul! — Burns said that he “never short-changed” the people of his home state.

So what should matter to Montana’s voters? The senator’s yard signs and bumper stickers pretty much sum it up, at least from his perspective: “Burns delivers for Montana.” Everywhere he goes, Burns talks about all the federal funding he’s brought back to the state and how his increasing seniority in the Senate means that the gravy days are still ahead. You don’t hear a lot about supporting the president — in two days in Montana, I didn’t hear Burns mention George W. Bush by name once — and you don’t hear much of anything about the need to keep a Republican majority in Congress. There’s little talk about Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid or House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, about the threat of investigations or impeachment or anything else. Instead, it’s Conrad Burns, the man who delivers the goods, vs. Jon Tester, a “soft on terror” liberal who’s determined to raise your taxes.

At Sunday’s picnic, Burns told his supporters about the debate the night before, and he said he wonders how Tester will pay for all the new spending he talked about there. But Tester didn’t spend much of Saturday’s debate talking about new government programs. What he talked about, mostly, was the ways in which a Republican president and a Republican-controlled Congress have turned a budget surplus into a budget deficit, created a “birth tax” for future generations and dropped the ball in the war on terrorism.

Tester and his supporters accuse Burns of running against a caricature of the Democratic candidate because he can’t beat the man Tester is — a third-generation farmer from Big Sandy who, as the president of the Montana Senate, helped the state Legislature deliver a balanced budget ahead of schedule this year. Tester is unquestionably more liberal than Burns is, but he’s also less liberal than Burns would suggest. Yes, Tester says that the country can’t afford to make Bush’s tax cuts permanent. But while a majority of Americans say the United States should set a timetable for withdrawing all of its troops from Iraq, Tester hasn’t proposed one: He says the president should come up with a “clear exit strategy,” and that he’d be happy to work with him on one once elected. On the other hand, Tester wants to see the Patriot Act repealed — a position that sets him to the left of most Senate Democrats. On the other other hand, Tester says he supports Americans’ right to keep and bear arms, and not just because so many Montana residents like to exercise that right by shooting elk and deer. “With things like the Patriot Act,” Tester said during Saturday’s debate, “we’d damn well better keep our guns.”

Tester says he wants to see the system of checks and balances restored in Washington, and he makes it clear that he’s unhappy with both Republicans and Democrats on that score. “I’ve served in the minority [in the Montana Legislature], and it’s tough to hold folks accountable in the minority,” he told me. Still, he said, he “would have liked to have seen” Democrats “do more” to hold the president in check. As for the Democrats’ disappearing act last week in the debate over the treatment of detainees? “Yeah, well, that’s unfortunate,” he said. “I think that speaks to the fact that it will be good to get back there, and offer some new ideas and hopefully move the party forward with the leadership skills I have.”

Tester pitches himself as a Montana Everyman. “I’m one of you,” he tells his audiences, and his physical appearance reinforces the message. He sports a flattop haircut that hasn’t been fashionable since Johnny Unitas played quarterback for the Baltimore Colts. When he speaks, he sometimes hunches over a lectern with both elbows planted on it. When he steps out from behind it, he thrusts his hands in his pants pockets, his jacket unbuttoned and bunched up in the back, his gut hanging over his belt up front. At a debate-night party at Butte’s Silver Dollar Saloon, Tester blended into the crowd so completely that he came off looking more like a barstool regular than a major-party nominee for the U.S. Senate.

Burns is different. He kept his jacket buttoned throughout Saturday’s debate, and he spent most of the night standing straight up behind his lectern. While he ditched his suit for khakis, cowboy boots and a big silver belt buckle for Sunday’s barbecue, there was still a sense of distance between him and his supporters. They approached him as if they were seeking an audience with a dignitary — they were — and he smiled and posed for pictures with them.

A recent Rasmussen poll had Tester over Burns by 7 percentage points. Both campaigns say the race is closer than that. Klindt points to a recent Gallup Poll that had Tester up among likely voters by a within-the-margin-of-error 3 points; Tester spokesman Matt McKenna said he hasn’t seen any poll — “public, private, rumored or whatever” — in which Tester trails Burns. There are still six weeks until Election Day, still a lot of time for the intensely retail politics that are possible in a state with fewer than 1 million residents, still a lot of time for federal investigators to do whatever they’re going to do, still a lot of time for Burns and his supporters to introduce Tester to voters their way.

Burns took a swing at Tester’s common touch Saturday night by asking him if he knew the going price for a pound of copper, the substance that made Butte a boomtown nearly a century ago. Tester had seen it coming — “$3.43,” he said instantly — and Burns was reduced to grilling his challenger about the price of platinum and palladium. Tester asked Burns whether he knew the price of an acre of land in Chouteau County, and the silly “gotcha” game came to a quick close.

Slightly more substantively, the senator’s campaign has launched a series of TV spots suggesting that Tester is a tax-and-spend liberal and a liar and a wimp on terrorism. “This is not a news flash, but Burns is running the most negative and false ads of any place of the county,” said Montana Gov. Brian Schweitzer, who lost to Burns in 2000 and is now campaigning hard on behalf of a candidate who is very much in his own plain-talking Democrat mold.

Both campaigns expect independent expenditures to increase dramatically as November approaches. The race is that close, and a little money goes a long way in a state this small. The Montana Democratic Party has launched a Web site called BuyingBurns.com and produced ads accusing Burns of failing to provide U.S. troops and veterans with the equipment and support they need. The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee has produced an ad attacking Burns for accusing firefighters of doing a “piss-poor job” of fighting a Montana forest fire; an official with the state’s broadcasters association has advised TV stations not to air the ad out of fear that Burns’ intemperate language would violate FCC decency rules.

The Montana GOP has distributed a mailer accusing Tester of being soft on sex predators; he voted against Internet filters on library computers after the state’s librarian testified that the bill was unnecessary because the libraries already had such filters. The National Republican Senatorial Committee has attacked Tester for inflammatory comments other people have posted at Daily Kos.

While fundraising appeals for Tester appear frequently in the pages of Daily Kos, McKenna says that Tester’s campaign has no control over Markos Moulitsas Zúniga, let alone over the random people who may post comments on his site. Klindt says Daily Kos is fair game; if Tester has the support of such “extreme” liberals like Moulitsas, Klindt says, he must be telling them something different than what he’s telling folks back home in Montana. It’s a sign that Tester is “not a Montana Democrat, he’s a Massachusetts Democrat.” McKenna’s retort: “People in Montana don’t care who Markos is. They don’t know who he is, and they wouldn’t care if they did.”

Conrad Burns and his supporters would like to be able to say the same thing about Jack Abramoff. “The only people [the Abramoff question] seems to be an issue for is the national press that continues to want to write about it ad nauseam,” Klindt said Sunday afternoon. “We’re talking about the issues that [Montana residents] are going to base their votes on.” On the morning of Nov. 8, he’ll know whether he was right.