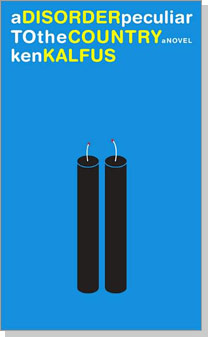

There have been quite a few 9/11 books out in the past couple of years, but few of them dare to be satiric. “A Disorder Peculiar to the Country” does. Did you worry at all that readers might not be ready for that yet?

No, the readers worth having are adventurous and open-minded, and I think many are more than ready for writers to take on 9/11 and the other catastrophes of our recent history.

In fact, I think there’s a great deal of frustration out there over the course of current events. We need satire and black comedy, as well as all the other literary strategies, to pierce the sanctimony, cant and hypocrisy that have come to shroud our public life.

Why did a novel about divorce strike you as a good way to approach writing about 9/11? Or was it the other way around?

The idea for the novel came to me in the weeks after Sept. 11, at a time when, reflecting our grief, the media was glorifying the victims of the attacks, calling them heroes, as well as perfect husbands and wives. I felt that through these clichis we were dehumanizing the dead and robbing them of the particularness of lives that were probably as normally messy as our own. Given what we know about the frequency of divorce and the extreme bitterness that often accompanies it, I supposed that if 3,000 people were killed in the towers that morning, then there must have been at least a few spouses relieved and gratified by the end of the day.

Starting there — and after arranging for Marshall and Joyce to be disappointed by each other’s survival — I wanted to take them through the other garish events of our recent history, again making them experience current events in unexpectedly personal, and increasingly ludicrous, ways.

Some of the things the divorcing couple in your novel do are so extreme it’s tempting to think they’re exaggerated, but then again, divorce makes people crazy. Did any of your characters’ antics come from things you know happened in real life?

Not specifically; for example, I don’t know of anyone, locked out of the bathroom by his spouse, who defecated in the kitchen sink. That happens to Marshall early in the novel — and they don’t even have a garbage disposal! But I’ve heard stories about some unfortunate divorces in which the hateful passions and bad behavior far exceed those in the novel. In fact, both Joyce and Marshall each still bears painful, self-sabotaging memories of having once loved the other. Some divorcing couples lose even this.

Your past couple of books have been set in Russia and deal with Russian themes. What was it like to come back to the U.S. as a setting?

I never considered myself a writer exclusively on Russian themes, and God knows my expertise wouldn’t carry me very far if I did. I do believe that America has recently passed through a pivotal moment in its history, offering plenty of opportunity for literary exploration. We’ll be writing about the Bush years for a long time, I think. I myself hope to return to Russian subjects some day, as well as take a shot at other places and themes.

The novel’s title is peculiar itself. Can you describe how you settled on it?

It comes from a 1760 essay by the British writer Oliver Goldsmith, author of “The Vicar of Wakefield.” Here’s the relevant sentence, from which I’ve also drawn my novel’s epigraph:

“They are afflicted, it is true, with neither famine nor pestilence, but then there is a disorder peculiar to the country, which every season makes strange ravages among them; it spreads with pestilential rapidity, and infects almost every rank of people; what is still more strange the natives have no name for this peculiar malady, though well known to foreign physicians by the appellation of Epidemic terror.”

Goldsmith is writing about the public manias that swept his nation two centuries well before the advent of the electronic mass media that regulate our passions today. “A Disorder Peculiar to the Country” leads Marshall and Joyce through the anthrax scare, the Afghan and Iraq wars, the collapse of the stock market bubble and the other “strange ravages” that have plagued our nation in the course of the Bush administration. Propaganda has become integral to their lives, making Marshall and Joyce, like the rest of us, keenly suspectible to “Epidemic terror.”

Excerpt from “A Disorder Peculiar to the Country”

Chapter One: September

On the way to Newark Joyce received a call: the talks in Berkeley had collapsed, conclusively. She closed her eyes for a few moments and then asked the driver to turn around and head back through the tunnel. It was still early morning. She went directly to her office on Hudson Street to sort out the repercussions from the negotiations’ failure — and especially how to evade blame for their failure. About an hour later colleagues were trickling in, passing by her open door, and Joyce thought she heard someone say that a plane had flown into the World Trade Center. The World Trade Center: the words provoked a thought like a small underground animal to dash from its burrow into the light before promptly scuttling back in retreat. She wasn’t sure she had heard the news correctly; perhaps she had simply imagined it, or had even dozed off and dreamed it after less than five hours of sleep the night before. Fighting distraction, she pondered the phrasing of her report, resolved not to be defensive; at the same time she wondered whether something had just happened that would dominate the news for months to come, until everyone was sick of it. In that case there would be plenty of time to find out what it was. She presumed the plane had been a small one, causing localized damage, if it was a plane at all, if the World Trade Center had been involved at all. The towers weren’t visible from her office window, but she could see several of the company slackers in the adjacent roof garden, smoking cigarettes and looking downtown. She worked for a few minutes and then suddenly she heard screaming and shouts. She thought someone had fallen off the roof.

Even now Joyce moved without hurrying, careful first to save what was on her screen. If someone had fallen she would shortly learn who, and the consequences would play out either with or without her. But as she stepped through the door to the roof she understood from their continuing shrieks what her colleagues had just witnessed: a second plane striking the World Trade Center. Every face of every man and woman on the roof was twisted by fear and shock. One belonged to the unyielding, taciturn company director, who had never before been seen to express emotion; now his mouth dangled open and blood rushed to his face as if he were being choked. Among her colleagues tears had begun to flow only a moment earlier. Women buried their faces in the chests of coworkers with whom they were hardly friendly. “No, no, no, no,” someone murmured.

Joyce turned and saw the two pillars, one with a fiery red gash in its midsection, the other with its upper stories sheathed in heavy gray smoke. Sirens keened below. She could hear the crackle and chuffing of the burning buildings more than a mile away.

Nearly everyone in the firm had now come onto the roof, crowding shoulder to shoulder. Joyce stood among her colleagues rapt and numb and yet also acutely aware of the late summer morning’s clear blue skies that mocked the city below. A portable radio was brought out. Joyce’s colleagues haltingly speculated about what had happened, the size of the planes, how two planes could possibly have crashed in the same place at the same time. Their conversations withered in the heated confusion and terror spilling from the radio.

After a while one of the towers, the one farther south, appeared to exhale a terrific sigh of combustion products. They swirled away and half the building, about fifty or sixty stories, bowed forward on a newly manufactured hinge. And then the building fell in on itself in what seemed to be a single graceful motion, as if its solidity had been a mirage, as if the structure had been liquid all these years since it was built. Smoke and debris in all the possible shades of black, gray, and white billowed upward, flooding out around the neighboring buildings. You had to make an effort to keep before you the thought that thousands of people were losing their lives at precisely this moment.

Many of the roofs in the neighborhood were occupied, mostly by office workers. They had their hands to their faces, either at their mouths or at their temples, but none covered their eyes. They were unable to turn away. Joyce heard gasps and groans and appeals to God’s absent mercy. A woman beside her sobbed without restraint. But Joyce felt something erupt inside her, something warm, very much like, yes it was, a pang of pleasure, so intense it was nearly like the appeasement of hunger. It was a giddiness, an elation. The deep-bellied roar of the tower’s collapse finally reached her and went on for minutes, it seemed, followed by an unnaturally warm gust that pushed back her hair and ruffled her blouse. The building turned into a rising mushroom-shaped column of smoke, dust, and perished life, and she felt a great gladness.

“Joyce, oh my God!” cried a colleague. “I just remembered. Doesn’t your husband work there?”

She nodded slowly. His office was on the eighty-sixth floor of the south tower, which had just been removed whole from the face of the earth. She covered the lower part of her face to hide her fierce, protracted struggle against the emergence of a smile.

They had been instructed to communicate with each other only through their lawyers, an injunction impossible to obey since Joyce and Marshall still shared a two-bedroom apartment with their two small children and a yapping, emotionally needy, razor-nailed springer spaniel Marshall had recently brought home without consulting anyone, not even his lawyer. (The children had been delighted.) In the year since they had begun divorcing, the couple had developed a conversation-independent system for their day-to-day lives, mostly centered on who would deposit the kids at day care (usually Joyce).

Excerpted from “A Disorder Peculiar to the Country” by Ken Kalfus. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced without written permission from HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, New York 10022.