Sixteen months after Hurricane Katrina opened America’s eyes about just how fragile the poor are and just how black and brown poverty remains, it’s hard to figure out what the public thinks about the hundreds of thousands of victims who are still displaced. It’s hard for me to figure what I think. Two different story lines battle it out in the media. One is about the hardships the New Orleans exiles face, the other is about the hardships the refugees themselves are inflicting on the cities where they now live.

These largely poor, largely black refugees face the end of free housing and other post-disaster public assistance. At the same time, they are being blamed for crime and social dysfunction in their new homes. Just as unsurprising as the racist fables about bestial black hordes running amok in the SuperDome after the storm are the more recent stories from Houston, where 100,000 refugees have worn out their welcome.

Houston is now experiencing a crime wave and a surge in murder, allegedly presided over by lawless, rampaging “Katricians.” Katrina evacuees were either suspects or victims in 59 killings in the first eight months of 2006, or one in five Houston homicides. They have become the poster people for fear-mongering Houston gun dealers and the subject of much public debate. Kinky Friedman, erstwhile Texas gubernatorial candidate and supposed political maverick, dismissed them as “thugs and crackheads.” I am surprised and chagrined to say that I can relate to the people of Houston.

As much as racism created and sustains this situation, the fact is, poor folks can seem like unreachable creatures, ever needy, inscrutable and impervious to uplift, from another planet. I know because I come from the inner city, because I am very involved in community work, but also because, until recently, the equivalent of Katrina evacuees lived next door to me. Much as I didn’t want to admit it that first year, they were a blight on our middle-class neighborhood and simply did not belong there. I’m glad (and unsurprised) that they were evicted. Relieved. And sadly sure that, absent concerted and sustained intervention, they are doomed to go on living as they always have — like perpetual evacuees, dependent on the largesse of others, defeated by America’s cutthroat capitalism and blind to its well-disguised avenues of escape.

Neighborhood gossip, to which I was necessarily not privy until it was too late, was that the “Smiths” were living in the house via Catholic Charities. Maybe it was Catholic Charities, maybe it was Section 8 — who knows and what’s the difference? In any event, and given the blur of any move, it took me a few days to notice that black people lived next door (we were the only two black families) and that a never-ending stream of children ebbed and flowed from their house at all hours of the day and night. After two weeks or so, I calculated that there were seven kids (plus one mom and four surnames) next door. Their house, like mine, has three bedrooms, one bath. It was, of course, the male teenagers that most caught my eye.

As a single mom of two tots, the young men worried me, mostly because they were so idle, sauntering aimlessly down the center of our busy street, lolling on their tiny porch, riding seatless bicycles in languorous, unpredictable, traffic-snarling circles. They were going nowhere very slowly. The yard overgrown, untended and strewn with litter in a neighborhood where the men often came home for lunch to tend already manicured lawns and plant new shrubbery. Why no team uniforms on these kids, no backpacks, no school projects carted home in cardboard boxes?

Unsmiling, they watched me, never crossing the driveway to help with my packages like the other families did, hip me to the garbage schedule, introduce themselves. Growing up, I learned the primary lesson of inner-city survival: Never show fear. Grown, I also knew that ghetto toughness is a necessary mask its purveyors are all too ready to shed; I made eye contact and was proactively nice from Day One. If I didn’t give them the benefit of the doubt, who would?

I learned all their names and gave each a friendly smile — Mom, too, when she took her rare TV breaks for air. Surprised and grateful, whenever they saw my soccer mom minivan pull up (carless, they were ferried about by a succession of white ladies with the lanyards of various social service agencies dangling round their necks), whoever was lolling about greeted me warmly. I thought we were off to a good start when they called me “Miss Debra” unprompted. Ah, I thought. Poor, but with home training, just as I had been. I can work with this. And the youngest two became instant playmates with my own. Alas, I relaxed too soon.

Quickly, my fears of violence, crime or drugs emanating from their home were squashed, but I was there less than two weeks before receiving the first of several visits from the police investigating child neglect claims from next door. Still, that first year, I said nothing when they ran about shoeless and coatless in the frigid winter; I knew they had ragged outerwear and their mother was always home. I said nothing when they hit each other in the head with the huge plastic soda bottles they were never without and yelled so loudly at each other that heads popped out of doors for half a block in each direction — they were playing.

I took them with us to the park, to baseball games, and to most of the cultural events my family attended. Their mother always said yes before I could even finish the offer and never wrote down my offered cellphone number. Before I accepted that Sam’s Club’s offerings were more than my small family could efficiently consume, I took a chance on sharing my extras with “Mary” and she gratefully accepted. So gratefully that, before long, she was sending the kids over with requests: “Mama say we need sugar.” I sent over a 5-pound bag. A week later: “Mama say we need sugar.” “Mama say we need orange juice.” “Mama say, we hungry.” Each request came complete with prolonged, drug-bust-style banging on my window though the doorbell is brightly illuminated. “Mama say we need meat.” “No, she say we need four rolls of toilet paper. And soap.” “You don’t got no sour cream chips?”

They had no tools, no salt for the sidewalks, no batteries for the broken toys that littered their yard and which the kids hopefully offered in exchange for the use of mine’s Toys “R” Us bonanza. When the child I sent home to be bandaged (they played so roughly) came back still bleeding and undisinfected, I left a Megalo-Mart, industrial-size box of bandages and a four-pack of Neosporin on the broken porch chair I used as the drop site for my donations. The next few days, I watched the Smith kids run about festooned head to toe in Winnie the Pooh steri-strips. The next time “Mama said we need Band-Aids” I said I was all out.

It was this summer, though, that I reached my tolerance limit. I learned that they were using my kids to score free snacks at the corner gas station. My kids. Begging. I nearly broke my ankle stepping into a foot-deep hole they’d dug in my front lawn. I found my son playing with a claw hammer lying abandoned in their junkyard of a backyard and my daughter trying to heft a 12-pound bowling ball. But the kicker was the youngest two’s increasing demands that I be their mother. When I rubbed sunscreen on mine, it wasn’t enough that I offered it to them — big-eyed and pleading, they begged me to rub it on them, too. They peremptorily ordered cones when I took mine to meet Mr. Softee. Seeing me strap the kids into their car seats, they flew outside saying, “Mama say we can go, too.”

They insisted on equal access to my kids’ bikes and toys; I’d come home to find them playing on my porch and in my backyard, asking when dinner was. They strew their garbage everywhere like birds molting feathers; Mary would wave at me from her filthy couch when I couldn’t stand the trash in her yard anymore and would pick it up. I offered to pay her teenagers $10 an hour to do yard work but “it’s too hot.” Just as well, because when one finally accepted the offer, he quit after an hour and left my lawn mower and supplies where he dropped them, without a word to me. Last Fourth of July, they were in the backyard blowup pool with my kids from 8 a.m. til 8 p.m. I gave them breakfast, snack, lunch, snack, dinner, snack. When I sent them home for towels, they came back with ragged sheets and grimy curtains to dry off with. Never a sighting of Mom. As I forced them to go home so we could all get some sleep, I decided I’d had enough.

If I’d wanted nine kids, I’d have had nine kids.

I remained friendly, but I disengaged. No more donations, no more trips. Just a friendly neighbor, no more a resource. No more surrogate mom.

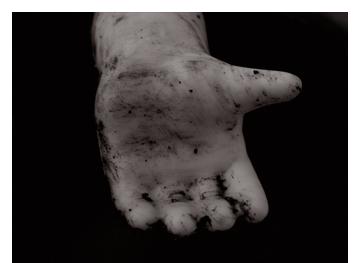

Soon afterward, they were evicted, and left behind a house so filthy and battered, it has taken contractors four months to repair the damage. They left the door hanging open and when I stepped in to close it, the stench nearly made my knees buckle. Junk was everywhere. The basement was flooded, food was stuck to the floor and walls, every kitchen surface was scorched and blackened. Mouse droppings made a carpet. As well, they’d vandalized my backyard and garage and keyed the entire driver’s side, the side nearest them, of my car. Windows, mirrors and finish.

Wherever they went, I know it wasn’t under their own power, arrangement or dime. No doubt those energetic, well-meaning white ladies with their social services lanyards worked their paperwork magic to save the Smiths for another year, another resentful neighborhood, another step down, or at best sideways, on the ladder of hope. Events like Katrina, and programs like Section 8, make the poor visible to us but they don’t make them any easier to reclaim. Or to love. Most of the Katrina evacuees who remain displaced are the hardcore, long-term, helpless poor, like the Smiths, and God only knows what will become of them when our patience wanes. However many begrudged millions we pour into the welfare system, the fact is that we abandoned these folks at birth and they know it. We shower them with Winnie the Pooh Band-Aids when they need heart transplants and, like Houston, we just wait to see which will drag themselves to success, which we’ll dump elsewhere, which we’ll bury, and which we’ll incarcerate.

The poor will always be with us but I’m glad the Smiths are gone. My heart breaks for them, but also for their new neighbors.