For most of the 20th century, the struggle of the Palestinian people was to prove themselves to the world as a “nation,” something more than a collection of unaffiliated Arab squatters who happened to make their home on a particularly hot parcel of holy land. But the invisible process by which peoples graduate to nationhood is shrouded in mystery. A nation, as a rule, possesses an illusory timelessness. Its inhabitants are tied to one another, and to their land, by prehistoric bonds that stir the hearts of patriots yet elude definition. Nations are not created in the present, they emerge from the past, like Athena from the forehead of Zeus — fully grown, and armed — appearing to all the world to have existed forever. A nation makes its home in a state, with sovereignty over its people on its “ancestral” lands. Nations that have persisted without their own states should, according to the logic of self-determination, have statehood bestowed upon them. But those peoples who have failed history’s test do not get states and never will.

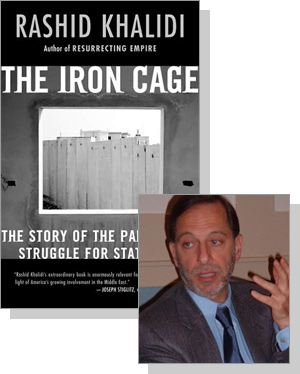

Reading “The Iron Cage,” Rashid Khalidi’s elegant history of failures and disappointments in the Palestinian quest for statehood, it is impossible not to conclude that the above puzzle encapsulates the terms of the Palestinian dilemma, one that has been dramatized by the astounding success of a competing national project in the territory both Palestinians and Israelis claim as their home.

Though one still hears, from certain disreputable quarters, the claim that the Palestinians are merely Arabs, and therefore should content themselves with residence in one of “the other 22 Arab states,” most of the world now acknowledges that the Palestinians are a nation, entitled to self-determination, presumably within a state of their own. The question that remains is why they have not achieved it.

“Palestinian Identity,” Khalidi’s landmark 1997 study of the formation of Palestinian national consciousness before World War I, deftly untangled the mesh of overlaying identities shared by the residents of Palestine — Arab, Ottoman, Muslim or Christian, and Palestinian — to demonstrate authoritatively that, 50 years before Golda Meir’s infamous declaration that “there are no Palestinians,” Arab residents of Palestine spoke of a “Palestinian nation.”

Khalidi’s “The Iron Cage” picks up where “Palestinian Identity” left off, considering the situation of the Palestinians beginning after the war, when the British took possession of Palestine under a League of Nations mandate and issued the Balfour Declaration, whose stated intention was to preserve for the Jewish people a national home in Palestine. As Khalidi notes, the very structure of the mandate conferred a proto-state legitimacy on the Zionist project and extended no such rights to the Palestinians; this distinction, in his telling, would prove to have baleful consequences for the Palestinians, under the mandate and long thereafter. In considering this situation, “The Iron Cage” attempts to answer a question left over from the prior book, in which Khalidi noted that explaining the “failure thus far to achieve statehood and sovereignty … is a central problem of modern Palestinian historiography.” “If the Palestinians had such a strong sense of identity before 1920,” he explained to me, “why did it all go so wrong for them?”

In a refreshing contrast to the yammering bazaar of complaint and allegation that has dominated American public discussion of the Middle East since Sept. 11, 2001, “The Iron Cage” is a patient and eloquent work, ranging over the whole of modern Palestinian history from World War I to the death of Yasser Arafat. Reorienting the Palestinian narrative around the attitudes and tactics of the Palestinians themselves, Khalidi lends a remarkable illumination to a story so wearily familiar it is often hard to believe anything new can be found within.

He spoke to Salon at his office at Columbia, where he heads the university’s Middle East Institute.

This book begins during the British Mandate, but your depiction of that era departs from the conventional narrative.

This book is an attempt to talk specifically about Palestinian history, not the history of the conflict or the history of Israel or Zionism. And there are, as you suggest, many versions of the Palestinian story in this era. One says, essentially, that the Palestinians entirely deserved what they got; they missed a number of opportunities, and were mired in backwardness by comparison with the Yishuv [the Zionist community in Palestine] and later with Israel. That version, both in scholarly work and in popular understanding, is quite widespread. There is another Palestinian and Arab version of the story, which has it that the Palestinians were overwhelmed by forces beyond their control, were helpless victims and had no agency — they could have done nothing else. They were overwhelmed by a tragic fate. I am actually trying to deal more with the latter than the former. The former … whatever. I address it in the book; I don’t think it’s grounded in historical reality.

My focus is on the Palestinians, and on an issue that I was surprised to discover had not really been addressed, which is the Palestinian view of statehood, the idea of state power and governance. No one, it seems to me, has asked, Why did the Palestinians not establish a state before 1948? Why have they failed since to do so? Implicit in both of the narratives that I reject are answers to these questions. The first one says, Because they were backward and stupid, and the second, Because they were overwhelmed by a superior force. But I don’t think either of those answers is sufficient.

You quote a French diplomat in Syria who described the mandate’s restrictions on the Palestinians as “the height of illogic.”

The British saw the Jews as more or less like themselves: a people, a national group. There was anti-Semitism — there was profound anti-Semitism in the British mandatory administration of Palestine — but officially, institutionally, in the terms of the Balfour Declaration, the mandate and the League of Nations, the Jews were a national group. The Arabs were not seen in those terms; they were not a national group and did not exist as such. The words Arab and Palestinian are not in the mandate. There are more articles about antiquities and archaeology than about Arabs or Palestinians.

From the beginning, the British assumed that they could finesse the issue of the Arabs; they gave them institutions, religious institutions, primarily, which the British hoped would keep them busy, divert them, distract them, give them a certain degree of status. The Jews were a people, and the Jewish Agency was given prerogatives and rights according to the terms of the mandate. There wasn’t an Arab Agency because the Arabs, in the British view, were not equal to the Jews. Even at a time when the Jewish population of Palestine was rather small, they had diplomatic representation, the ability to take issues before the League of Nations and so on. The Arabs, during the entire period of the mandate, never achieved this because of the way the British saw them. Over time, the British were forced to modify this view, and by the late 1930s the Palestinians were able to come to the table. But it was two decades too late.

This seems to embody the paradox: You depict a kind of Catch-22, in which the failure to become a state can be explained by the failure to have already been a state.

Given the way the game was loaded in the mandate period, it would have been very difficult, if not impossible, for the Palestinians to achieve any form of sovereign statehood in Palestine — even when they were an overwhelming majority of the population. But there might have been ways for them to change the rules of the game or go outside of the game, and they failed to do that.

The might-have-beens of history are a sort of foolish exercise, but I do suggest that the Palestinians could have done such a thing. The Palestinians had more agency than one version of Palestinian history would suggest — nothing was entirely inevitable, certainly not before Hitler came to power. Up to a certain point, had the Palestinians managed to change the rules of the game, adopt a different approach, things might have been different. But in the context of the mandate rules, at least, there was no way that any other outcome was likely.

The religious institutions that were ostensibly at the head of the Palestinian community, as you observe, were essentially created by the British.

I’m not sure anyone has ever fully teased out and pulled together the degree to which these institutions were completely new and artificial, created by the British for the Muslim community. Consider the Supreme Muslim Council, and the grand mufti of Palestine, institutions and positions that had never existed in the history of the country, which the British created on the basis of patterns of indirect control they had employed elsewhere — Egypt, especially, but also in Ireland and India.

There’s an overtone here of Orientalist benevolence: Let’s give these people what they know.

You see this in Iraq as well. There’s a terrible denigration of the political level of these populations prior to British rule. The British come in thinking they are purveyors of civilization, while the natives are basically barbaric savages at the head of whom are a few semieducated urban effendis, who pretend to speak for the people but in fact are ignorant. But in fact the British came in and destroyed institutions of democratic governance and parliamentary representation that had developed, with great difficulty, during many decades of Ottoman rule. I quote one Palestinian deputy, who exclaims, in 1930, “We had a government of our own in which we participated. We had parliaments.” But now they had nothing.

There is surely an irony here, with the Palestinians, not a particularly pious people, led by a pretend religious figurehead created by the British.

Anybody who looks at the history will say, no, not a particularly pious people. Quite the contrary, in fact, a particularly secular people, in this period and for decades thereafter. The mufti himself was not a pious character — he was a secular figure until he was anointed by the British.

I don’t often quote Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. But he said a wonderful thing the other day, in a vitriolic and obnoxious attack on secular intellectuals in Iran. He said something like, “For a hundred and fifty years, these people have controlled the universities, they have taken over, they have dominated the country.” This is a thesis that I only wish some people in this country would pay a little attention to. There was, in the Arab world, what Albert Hourani called a “Liberal Age.” In the Arab world, in Turkey, in Iran as well. The Islamic revolution in Iran, among other things, was a reaction to the dominance of secular ideas in this part of the world.

Anyone who ignores the first two decades of the mandate and just looks at what happens in the late 1930s is missing a great deal, and the mufti’s role in helping the British keep control of Palestine in the first few decades of their occupation is crucial, just as the role of the British in establishing Zionism in Palestine is indispensable. You would not have had a successful Zionist project without everything the British did between 1917 and 1939. The individual figure of the mufti is less important, historically, but the British would not have been able to control Palestine as they did had they not been able to co-opt an important segment of Palestinian notables through the religious institutions they created.

You write of the mufti that his would not be the last time the Palestinians suffered “from the damaging conflation of the national cause with the personality of an overweening leader.”

Well, that’s my judgment of both the mufti and Arafat. The mufti was an old-style notable politician who could play both sides of the street, doing deals in backrooms, just as Arafat was able to navigate the shark-infested waters of Arab politics — which is where he made his career. Arafat did not make his career fighting Israelis. He made his career by reestablishing the Palestinian national movement, and fending off attempts by Arab governments to control the Palestinians.

In the book we see a kind of division between two eras of Palestinian history: There is the British Mandate era, until 1948, and then a post-1964 Palestine Liberation Organization era, with a sort of Dark Ages in between. Is there a difference?

In both of these eras, there is a major element of continuity: the limited degree to which the Palestinians focus on the question of the state and state power right up to the present. I don’t think that explains everything, but it is an important point, and one of the main focal points of the book.

The Dark Ages, as you describe them, in fact begin during the Arab revolt [from 1936 to 1939] and continue until the 1960s. The Palestinians lost agency, and their effort in those years was to regain that agency, to become actors in their own drama, which they were not, for decades.

So the revolt, although it brought about a slight change in British policy, was a pyrrhic victory?

Absolutely. It was a disaster, just like the second intifada. An utter disaster. This view of the revolt, in fact, is actually novel in Palestinian historiography. The revolt has generally been viewed as a heroic chapter in Palestinian history. Almost everybody, I suppose, realizes that it was a defeat in one way or another, but the extent to which it was a catastrophic defeat, the extent to which it brought about all kinds of other disasters, I don’t think has ever been fully recognized.

In the present moment, are the Palestinians at the start of another Dark Age, comparable to the post-1948 period?

I’m a historian and I try not to speculate about the future. It’s very hard to look at the present the way one looks at the past. But one of the things I suggest in the book is that it is not necessarily the fate of every people to end up with a state, and that might be what’s going to happen to the Palestinians. Certainly it has been what has happened to them in the entirety of their modern history up to this point. And it does not look like we’re moving toward a state — quite the contrary. I finished the book before the latest episode in Gaza. But what seems to me to be happening — at least to the Palestinian society in Gaza and, to some extent, to the entirety of Palestinian society under occupation — is the systematic destruction of the society. Not of people’s will. There is still a remarkable degree of social solidarity and mutual support; this has so far kept people alive. But there is a grinding process going on.

So maybe statehood is impossible?

Well, expulsion, or people just fleeing, is not likely, either. Expulsion, even if it were attempted, is not likely to be successful, and it probably can’t even be attempted. You know, you can deny visas to all the Palestinian-Americans in the world, you can deny residency, you can force anyone who has the means to leave. But you still have the highest population growth in the world, and you still have this extraordinarily stubborn people that’s clinging to its land and whose will is clearly indomitable — and who so far have had the social networks to enable them to survive.

The book contains a brief but very lucid account of various “one-state” ideas that have received a lot of attention in recent years, particularly as the emergence of a sovereign Palestinian state appears less and less likely; you note, critically, that those who foresee a single-state resolution “render no value judgments about it” and “do not advocate such a result; rather they perceive it as inevitable if present trends continue.” What are those present trends?

Irrespective of whatever international consensus exists, if current processes continue, there’s no possibility of two states. I don’t think it’s even contestable, frankly. If you keep the settlement blocs attached to Israel, and you keep the mechanisms of control, then you don’t have Palestinian sovereignty, and you don’t have statehood. I see nothing — nothing! — that should lead us to believe that there will be even the slightest relaxation of this suffocating and comprehensive regime of control. Look at how Gaza has been treated since the evacuation of settlements; Israeli control over Gaza is in some ways even more complete. The settlements are gone, true, and Israel doesn’t administer some aspects of life. But it still controls entry, exit, the economy, death, movement, everything.

In Gershom Gorenberg’s recent book about the first decade of the settlements, he depicts an essential paradox of the Israeli occupation, in which policymakers felt they could not keep the occupied territories, but they couldn’t leave them either. From this perspective, the withdrawal from Gaza is a bit like a magic trick —

Leaving and not leaving. It is a magic trick. I mean, it was a magic trick, but I think we’re seeing the screen lifted and the Wizard of Oz mechanics revealed. In fact, they never left. They’re getting away with murder in the sense that there’s no international opprobrium. But that doesn’t mean that the situation is not going to come back and haunt everybody.

The Israeli withdrawal from Gaza was negotiated with the United States, which, in exchange, consented for the first time to formally acknowledge the “facts on the ground” in the West Bank, the Israeli settlement blocs. What do you say to those who contend that “George W. Bush is the best friend the Palestinians have ever had, because he’s the first American president to call for a Palestinian state.”

In terms of the Palestine issue, Bush has been, I think, by far the worst friend possible to the peoples of this region. I think he has done an enormous disservice to the Palestinians and the Israelis by advocating a policy of force — throughout the region and the world, but in particular in Iraq, Palestine and Lebanon. He has reinforced the worst tendencies in the region. He has pushed us farther away from what was already a very distant possibility of a just, equitable, lasting resolution, and he has guaranteed boundless problems for the United States.

When [Ariel] Sharon came to the United States before the Gaza withdrawal, he was trying to get the United States to change a long-standing policy, which was its refusal to accept large-scale annexations. He succeeded. The president fundamentally modified the American position by saying that most Israeli settlements must now be seen as realities, which means that when the moment comes — if it ever does — for negotiations, the United States is committed to the Israeli position, which is that much of what’s left of Palestine has to be annexed to Israel. This is a major shift, and it may have lasting consequences. You can’t have a two-state solution if most of the settlements are annexed to Israel. You can have a “many-Bantustan solution,” a “multiple-prison-camp solution,” but you can’t have two states.

In the book’s last pages, you write that the Palestinians “must take the initiative and devise new forms and conceptions for the future,” which will be “more imaginative, more comprehensive, and more effective than those that have gone before.” What do you have in mind here?

There’s an expression in Arabic, “a situation where everybody does exactly what they please.” This is what you saw during the second intifada, and now, to some extent in Gaza — where all the major forces don’t seem in favor of a particular course, and yet the whole society is dragged in that direction by the actions of a limited few. I don’t think the Palestinians can afford that anymore. It’s a much graver situation than any I can recall, and the margin for maneuver that the PLO had at some points in its history, that even the Palestinian Authority might have had, simply doesn’t exist anymore. So I would ask, had I gone further in the book on this subject, to what extent can the Palestinians afford the complete lack of focus on their real national objectives? Is the structure of the Palestinian Authority of more harm than use to the Palestinians? And finally, to what extent is the continued use of violence just playing into the hands of the other side? I’m not suggesting it would be easy to stop the violence right now, but this is a debate that is going on among Palestinians, and has been for a while. These people firing rockets out of Gaza, they are bringing a rain of death down on Gaza. There is already the most awful campaign going on inside of Gaza, and maybe that would continue if there were no rockets, because you have a Hamas government, and there is an American-Israeli attempt to prevent elected political movements they don’t like — whether Hamas or Hezbollah — from continuing to exist.

A final question. You talk, in the mandate era, of the successful recourse to international diplomacy by the Zionist movement. Why, even half a century later, has the Palestinian diaspora not been such a force?

I’m not an American historian. But in American politics, it usually takes several generations for a community to cease to feel marginal, to learn English, to understand the way the levers of power work. And if you look at the Arab-American diaspora in the United States, it’s composed of two waves. The first came before the 1920s. But the second, more recent, and much larger, wave has come since the immigration laws were changed in 1965. Most of these recent immigrants — among which are the majority of Palestinians in this country — are by no means fully assimilated.

I think that the comparison to be made is to the complete ineffectiveness of the American Jewish community in the 1930s, after the rise of Hitler. Here you had a community that was large and apparently possessed all of the prerequisites of political power, but that had absolutely no ability to affect anything — immigration law, American policy toward Nazi Germany — in a friendly Democratic administration. Why? For the same reasons that the Arab-American community, which appears to be many millions strong, has been ineffective. First of all, there’s bigotry, racism and discrimination; in the 1930s it was anti-Semitism, and today it is anti-Arab and anti-Muslim. And second, they speak with funny accents and live in ghettos. It’s not Yiddish and it’s not the Lower East Side, but it’s still true for a large proportion of that population. Go to Paterson [N.J.]! They don’t speak English without an accent. They don’t know about the Constitution. They come from countries where you can’t be involved in politics or the secret police will drag you away. Most Arab-Americans are not the people you meet at Columbia or NYU. Now, you can look at kids in law school, at professionals, at rich people in the Arab-American community, and you can see that over time, the situation will change. But it’s not going to change in the short term.

As far as international diplomacy goes, there has not, to this day, been a full understanding of the international factor by any Palestinian leadership. To this day. This was, of course, not the case with the Zionist movement, which at its inception was a European movement. So of course they understood Europe — they were Europeans!

There was no Palestinian Chaim Weizmann.

No, no. Because Weizmann was not in Palestine. He eventually became president, but he was quintessentially a European. The shift in power to [David] Ben-Gurion takes place after the successful establishment of the Zionist movement, its implantation in Palestine. By this time you had a diplomatic effort, as well as a para-state structure, with a critical mass of population in Palestine. The two peoples are in completely different situations — it’s apples and oranges, and you just can’t compare them.

The PLO, to its credit, did a considerably better job of representing the Palestinians abroad — in Europe, in the Third World, in China — than the Arab Higher Committee ever did in the mandate era. But where [the PLO] utterly failed was with the centers of international power; with the United States, they failed. I don’t think they ever fully understood what had to be done — in the 20s and 30s with Britain, and from the 40s onward with the United States. Whereas Ben-Gurion was visiting New York, even before the United States was a global power. It shows how smart Ben-Gurion was. He was far ahead of Weizmann, and far ahead of most people in the Arab world. Except [Saudi King] Ibn Saud. He was close behind.