I spent my final 10 years at Catholics for a Free Choice refusing to take press calls about the “partial-birth” abortion ban. It seemed a no-win proposition. Rational arguments about protecting women’s health, preventing tragic births when the infant’s brief life would be filled with unbearable pain, and the doctor’s need to decide what type of abortion would be safest for her patient were simply too abstract to compete with even a measured and accurate description of what happens during this procedure, known medically as an intact dilation and extraction (D&X) abortion. The 20-plus-week fetus’ physical resemblance to a baby was the debate closer.

Even staunch pro-choice legislators had trouble when they looked at visuals of the D&X procedure. The late Catholic Sen. Daniel Moynihan first voted against banning it in 1995 and then voted for it in 1998. Moynihan said the procedure was just “too close to infanticide.” Fellow pro-choice Sens. Patrick Leahy and Joseph Biden, also Catholic, joined Moynihan in voting for the ban, with Biden recently repeating Moynihan’s oft quoted “infanticide” phrase on “Meet the Press” this April after the Supreme Court ruled in Gonzales v. Carhart that the ban on D&X procedures is constitutional.

Apparently the five Supreme Court justices in the majority, all of whom are Catholic, agreed with the senators. Their opinion upheld the federal Partial Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003, which prohibits the performance of a rare abortion procedure, performed most often in the second trimester of pregnancy, in which a doctor extracts the fetus intact, pulling out its entire body through the cervix and vagina, piercing the skull so that the head can pass safely through the cervix. The bill, or state variations of it, had been ruled unconstitutional by various courts, including the Supreme Court. None of these bills included an exception to allow the procedure to be performed when the woman’s health was threatened, which Roe and subsequent Supreme Court decisions held essential. Gonzales v. Carhart was closely watched as it was the first abortion case the post-Sandra Day O’Connor court would decide.

The opinion, written by Anthony Kennedy, who is considered the least orthodox of the five, was devastating. Beyond outlawing a method of abortion it deemed only possibly needed by a few women, the decision injected orthodox Catholic teaching into the interpretation of constitutional rights. Kennedy’s opinion, which affirms “the government’s right to use its voice and its regulatory authority to show its profound respect for the life within the woman” as it cavalierly dismisses the need a few specific women might have for this procedure, could easily have been written by the late Pope John Paul II or the current Benedict XVI. Women are invisible in this decision as they are invisible in the writings of recent — and not so recent — popes. Now it’s impossible for me to remain silent.

The orthodox Catholic preoccupation with the morality of physical acts to the exclusion of the context in which those acts occur is evident in the amount of space the Kennedy decision gives to the description of the medical procedure (approximately eight pages), with only a few paragraphs on the possibility that banning the procedure would “subject [women] to significant health risks.” Kennedy and his cohort are satisfied that this is a “contested question” and “medical uncertainty” places no ethical or legal requirement on the court or legislature. Nowhere in the decision are the health reasons that lead doctors to perform this procedure rather than others discussed. No ambivalence exists. No competing values need to be weighed.

After all, the Catholic hierarchy still forbids assisted reproduction in large part because sperm is collected by masturbation. The good of enabling an infertile couple to conceive does not outweigh the evil of spilling one’s seed. It still prohibits the use of condoms to prevent the spread of HIV because the condom is also a contraceptive. In the same way, the reasons why a woman might need the D&X procedure, such as when a deformity truly inconsistent with life is discovered late in a wanted pregnancy, are totally irrelevant to orthodox Catholic anti-abortionists and are absent from Kennedy’s opinion or concern.

Let’s face it: No abortion procedure is aesthetically pleasing. They are, as Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg noted in her dissent, “gruesome” — some more than others, but none do not trouble a gentle nature. I, like most people, would prefer not to think about how abortions are performed and I certainly don’t want to spend my time in an unwinnable debate over techniques that ignores social context. Most of us want abortion to be available when someone in our family needs one, but how it’s performed and just what the fetus looks like tend to go unexplored. But every woman knows that abortion includes a difficult “yuck” factor; honest discussion of the subject shouldn’t ignore that. The Kennedy opinion, however, ignores everything but that by leaving out the reality of how women and doctors deal with unintended pregnancy and abortion.

Even among physicians who regularly perform abortions, most limit their practice to the first 15 or so weeks of pregnancy with only 2 percent willing to do them after 20 weeks. Most women try to get an abortion in the first eight weeks of pregnancy and more than 50 percent succeed; 90 percent of all abortions are performed by the 12th week. This self-regulating instinct in doctors and women requires no reinforcement or preaching from government. We all get it: Abortion is not an unmitigated good; it is better to not need one; if needed, it is better to have one early; and it is a very serious situation when one needs one when the fetus is more developed.

At the same time, the overwrought descriptions of intact dilation and evacuation as “partial-birth” abortion, infanticide or killing babies who, if delivered that day, would be shaking their silver rattles and smiling, is ill-informed. Abortion statistics are difficult to gather in a timely manner since Reagan administration politics ended the Centers for Disease Control’s abortion surveillance program. For 2000, the Guttmacher Institute estimated that only 1.2 percent (16,100) of all abortions occurred at 21 weeks or later. About 2,200 of these, most of which were performed between 18 and 24 weeks, were D&X procedures.

Given these facts, it’s hard to discern the basis for the misguided concerns of politicians like supposedly “pro-choice” Joe Biden who not only support the ban on D&X abortion but impede poor women’s access to early abortion by their opposition to federal funding for Medicaid abortions. But the truth is, these positions are politically expedient.

Conventional wisdom holds that abhorring abortion while believing it should be a little bit legal can offer a “pro-choice” candidate moral cover. And second-trimester abortions and poor women are easy targets. The thrice-married Catholic Republican presidential candidate Rudy Giuliani declares in a single sentence his hatred of abortion, respect for a woman’s right to choose and nonchalance about Roe’s survival. Joe Biden’s “feelings” about morality are not different from Giuliani’s. Far too often the moralizers are Roman Catholics who should know better.

Moralizing about women’s lives is not, of course, an exclusively Catholic habit, but we Catholic feminists tend to sniff it out and want to snuff it out. When we see it in a Supreme Court decision our fear of being considered irrational fades. At the risk of providing yet another opportunity for that pit bull of Catholic orthodoxy, William Donohue, to cry anti-Catholicism, one must stress another aspect of orthodox Catholicism that is the foundation of the majority opinion in this case — its tragic view of women as either victims or sluts.

In her dissent Justice Ginsburg more than teases out the flawed moral frame and outdated understanding of women’s nature that dominates Kennedy’s opinion. “Ultimately,” Ginsburg notes, “the court admits that ‘moral concerns’ are at work … by allowing such concerns to carry the day and the case, overriding fundamental rights, the Court dishonors our precedent.”

What Ginsburg is too cautious to say is that those moral concerns are distinctly Roman Catholic. As the world, particularly the U.S., Europe and the United Nations, increasingly recognizes women’s sexual and reproductive rights as legitimate, the Vatican has called on its powerful members to reject such public policies wherever possible. And the five Catholic justices have used the “partial-birth” abortion decision to do just that. Kennedy’s words about the “bond of love” “mothers” have with their “child” could have been written by John Paul II, who exhorted the Muslim women of Bosnia-Herzegovina who had been raped by Christians to continue their pregnancies. He asked them to turn those rapes into “acts of love” by bringing those “children” into the world. The court’s refutation of the long-standing legal and medical distinction between a pre- and post-viable fetus in the claim that “a fetus is a living organism while within the womb, whether or not it is viable outside the womb,” and thus entitled to similar protection, could have come from John Paul’s encyclical “Evangelium Vitae.”

Like Bush’s wholesale appropriation of John Paul “culture of life” rhetoric, the opinion is an indicator of the extent to which sectarian Catholic thought and teaching has become the framework of public policy.

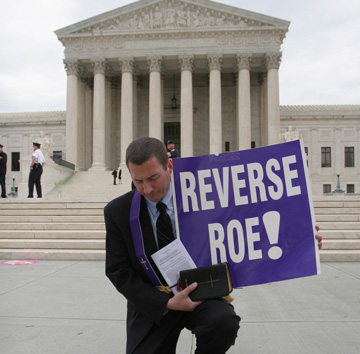

In this context, it seems unreasonable to maintain the facade of a court free of a religious test. For some time now, such a test has existed — and it is an orthodox Catholic test. We were ill-served by senators who, fearing that talking about what orthodox Catholicism requires of its adherents would subject them to charges of anti-Catholicism, confirmed justices who cannot distinguish the Constitution from the catechism of the Catholic church.

Defending so-called partial-birth abortions in this context becomes what defending the right to choose abortion has always been, a defense of religious liberty and women’s moral autonomy. I am now sorry I did not find a way to say that 10 years ago.