Dear Theater World,

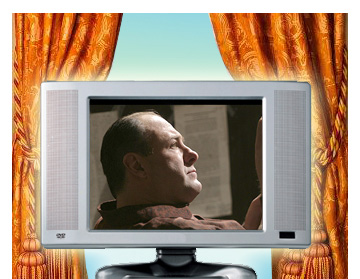

I know Sunday’s your big moment, and I don’t want to spoil anyone’s party, but I think you know not many people will be tuning in for the Tony awards that night. It’s not just because “The Sopranos” series finale will be on at the same time, though, frankly, that you scheduled the awards to run directly against it — essentially shrugging your shoulders at the culture-minded audience members you claim to court — does seem startlingly symbolic.

You seem to have trapped yourself in a system of theater creation in this country that is positively Soviet in its unwieldy, self-satisfied stuck-ness. A system that, for the last 50 years, has reacted to television not by learning from it but by “distinguishing” itself from it — and thereby neutering and bleeding itself into desiccated, rarefied irrelevance. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

Tell me something: How come the go-to insult for theater critics and theater makers is still the word “television”? And how come none of you who use it seem to have any idea how much you sound like grumpy old coots, sneering at the printing press, or the electric light? I say this as a friend, as someone who has acted in, directed and written for the theater: You have just got to get out more. I mean, the same elements that are considered avant-garde in the theater today were considered avant-garde in 1918. The theater still thinks dissonance is a daring musical gesture, and that nonlinear storytelling is new. It’s embarrassing how proudly it seems possessed by not only the aesthetic, but the ethos and issues of another era.

You know that people who write for film and television aren’t just doing it for the money anymore, right? They do it because their work won’t be developed to death by an endless supply of places with “mission statements,” because they know they will have more artistic freedom, more fun and more opportunities to do the kind of interesting work the theater once provided, about, you know, recognizable people in dramatic situations, struggling with the human condition.

If the theater is going to return to anything like its former position in our culture, it has to change. Why are some of you so resistant to the idea of marketing to young tastemakers, the 20- to 40-year-olds who enjoy sophisticated art and music, who are the potential defibrillators of the American theater? When you start producing more plays for and about the people in Nicole Holofcener’s movies, or David Chase’s television shows, you’ll be on the right track.

Some of you already are. There have been some good plays produced in the last 30 years — “Angels in America” sure was great — but there haven’t been enough of them. “Spring Awakening” and the upcoming “10 Million Miles” appeal to people who might not have been to the theater in a while, and that’s a very good thing. If you keep doing shows like that, keep producing plays that sound like they were written by people who might read Michael Chabon, or listen to the Decemberists, or watch “Weeds,” I promise you, more of those people will come to the theater.

But right now they’re more likely to see plays that sound as if they were written by the light of a candle in a Chianti bottle. Plays filled with cringingly unconfident writing that muddies the waters in order to make it all appear deep; writing full of insufferable name dropping and artless declaiming of Big Ideas, with a campy, brittle sense of humor right out of 1959, performed in a teeth-gratingly earnest, over-enunciated style that has become a parody of itself. Richard Greenberg’s insistent assertion of his bona fides as a collector of intellectual arcana in “Three Days of Rain,” the late August Wilson’s dogged refusal to trim his character’s verbal output to a level that would articulate their inner lives rather than the playwright’s high regard for his own ideas in plays like “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone” and Jon Robin Baitz’ determined obtuseness in plays like “A Fair Country” are symptoms of a theater community that has been too cloistered for too long.

Hasn’t our culture moved on a bit since, say, William Inge, and don’t we all kind of take it for granted, for instance, that sexual repression is bad? Why do we need to see yet another sexual awakening story, even if it’s by Terrence McNally (“Some Men”) or Jon Robin Baitz (“The Paris Letter”)? A lot of the better television shows, even back in 2003 or 2004, were weaving what was happening in the world into their stories in subtle, surprising, even funny ways, like it is in life, but the theater gave us two David Hare plays solemnly breaking the news that war is bad and George Bush is an idiot.

Some of you seem to think the problem is with the audience, and that the only prescription for what ails the theater is to redouble your commitment to doing work that is “important” and “ambitious.” I’ve got news for you: People aren’t staying away from the theater because it isn’t ambitious enough. They’re staying away because it’s relentlessly “ambitious,” because it keeps insisting on its own unique and righteous importance, despite all sad evidence to the contrary.

To be sure, when theater is great, it’s really great, and it can be transcendent. Of course, so can sculpture, and folk music, and animated movies. But the theater hasn’t been great for a long time now, and during that time, other storytelling forms, especially television, have seriously outpaced it. Do any of you think that there have been enough theater productions of note in the last 10 years that achieve the creative unity, the complexity, the appreciation of moral ambiguity, the timely insight, humor and, most important, entertainment value, of “The Sopranos”? Or “Six Feet Under” or “Arrested Development” or “The Simpsons” or “The Wire,” “The Larry Sanders Show” or “30 Rock” or “Deadwood” or “South Park” or “Prime Suspect” or “Curb Your Enthusiasm” or “ER” or “The Office”?

This is not accidental. It’s because the theater has been hijacked. It’s been commandeered by grant-proposal writers and dramaturges, by panel-discussion moderators and chin-in-hand bureaucrats, many of whom brook no more dissent than the Bush administration. To even suggest, at any of the endless symposiums that the theater community can’t get enough of these days, that the problems facing the theater might be solved by respecting the audience more instead of less, that perhaps, instead of designing condescending “outreach” programs, the theater might try educating itself, and listening to the people it’s been reaching out to, is to tempt the derisive wrath of a community whose motto might as well be “You’re with us or against us.”

This is why the theater many of us grew up with, that was so often moving, funny and fun, has been replaced by a bloodless, sexless, outdated facsimile. There are still exceptions, of course, like John Patrick Shanley’s “Doubt,” a play confident enough in its own ideas and emotional honesty to speak in a voice that’s lucid and thrilling instead of opaque and soporific. But most of the time when I see a play these days, I feel like I’m being read to from the journal of a bored, entitled graduate student. I often feel like I’d rather have watched a good episode of “Scrubs.”

The great artists of the theater’s Golden Era — many of whom would have scoffed at that characterization of themselves and insisted instead that they were craftsmen — great heroes like Abe Burrows, Noel Coward, Mary Martin, Bert Lahr, Frank Loesser and the rest, applied themselves to the modest and deeply difficult goal of creating work that was entertaining, and so, they invariably, and often inadvertently, created work that was profound. But now profundity is the unembarrassed goal. These days it seems like every other interview with one of you guys includes two or three unabashed pronouncements about your work’s importance. Way too many of you plead the case that theater people are great artists, unfairly ignored by a television-watching world that is too ignorant to appreciate you.

Which makes me wonder: Why are you asking for attention from people you look down on? It seems to me you should stop the us vs. them, and join the party. Because, and I say this only as someone who cares, you would do yourselves and everyone who loves you a big favor if you just broke down and got cable.