There's nothing like midsummer in New York to make a person acutely aware of the deprivations of city life. Does anyone grow up and move away, only to yearn for swarms of roaches and sweltering subway stations? For this country-mouse transplant, summer and the city are a cocktail that provokes the sincerest kind of longing; campfires, salty corn on the cob, fried clams and cans of beer sipped while dangling your toes in a dark lake -- these are the fabric of my summer fantasies. But short of a fairy godmother with a shore house, I've found only a few quotidian treats capable of breaking the humid gloom: a midnight thunderstorm, maybe, a mound of lemon ice in a paper cup -- and a little yellow cookbook by Elizabeth David.

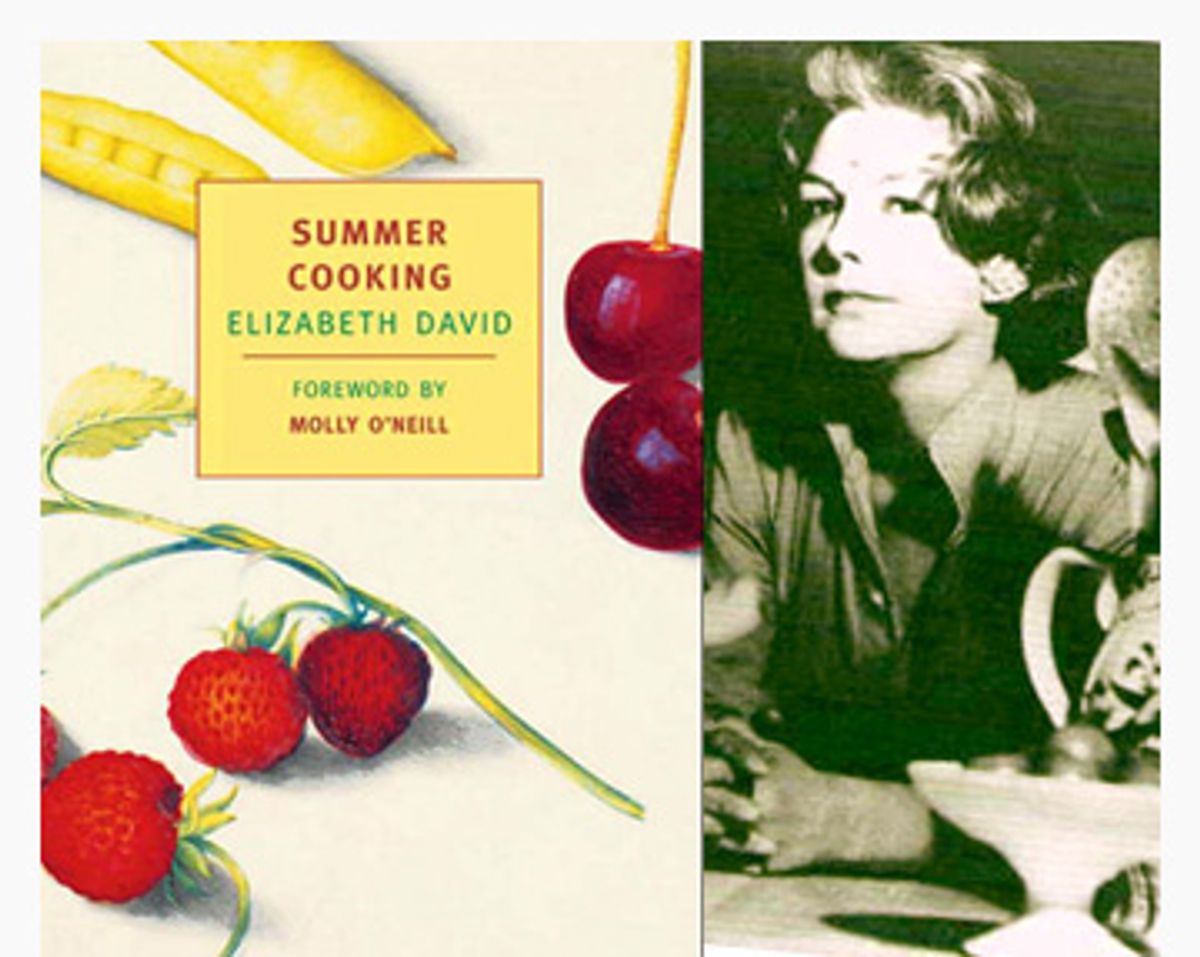

Decorated with a portrait of twin cherries, yellow runner beans, and the sweet, petite wild strawberries known as frais de bois, to urban eyes starved of July's sensual delights, the sunny cover of "Summer Cooking" seems to promise a storybook world, an alternate dimension composed of clean linen and overflowing European market baskets. Before her death in 1992, David was Britain's preeminent postwar "cookery" writer and the prescient precursor to today's high priestesses of seasonal cooking -- Alice Waters has called David her "greatest influence." In 1955 she released the slim volume of warm-weather buffet and picnic dishes, after her first three books, "A Book of Mediterranean Food" (1950), "French Country Kitchen" (1951) and "Italian Food" (1954), had made pine nuts and polenta part of the modern cook's pantry and had single-handedly shaken British kitchens to their flavorless foundations. Written in her signature spare style but unencumbered by the exacting research and scholarly tone that marked her previous books, "Summer Cooking" was itself a kind of holiday, a light exercise regarded by David and her audience as a departure from the author's "serious" work as a Mediterranean culinary missionary.

But don't let the unsophisticated subject fool you into expecting only cheese sandwiches and potato salads. For all its simplicity, "Summer Cooking" is a wonderfully subversive volume -- every bit as unexpected and enchanting to read today as it must have been 50 years ago, when England was just stirring from its wartime fast and garlic was an ingredient still capable of provoking controversy. David elevates the adequate to the artful; when potatoes make an appearance on David's page, they may be plainly dressed, but they are also liberally accessorized with Middle Eastern spices or just-laid eggs and the European herbs of the season. A daughter of privilege who put her inheritance in hock when she was barely grown to buy a boat and sail the Mediterranean with her older lover, and later lived in Greece, Egypt and India as an employee of the British Ministry of Information, David earned her place in gastronomic history by being one of the first writers to suggest that thoughtful food and cooking itself could be a means of escape.

Now, 15 years after her death, that voice remains a singular note in the chorus of her contemporaries and acolytes, neither frankly amiable like Julia Child, nor seductively literate like M.F.K. Fisher, nor playfully mod like Nigella Lawson. No matter how trivial the point, David speaks her mind. (On rosemary, for instance, this decree: "It is disagreeable to find those spiky little leaves in one's mouth.") And as a leader she expects no less assurance from her audience. David does not baby-sit; her recipes -- if those impressionistic paragraphs can even be called such -- speak to a capable reader and cook who is less interested in instruction than in inspiration (and, in fact, would bristle at any author's attempts at coddling). Hers are books for and by a capable and confident cook, dispatched with the color, authority and the ever-so-slightly chilly air of a rebellious blueblood. I never read David and wish I could have been friends with her; I read David and wish I could have been her.

But the purest thrill of "Summer Cooking," as in all of David's volumes, is the nearly pugilistic punch of pleasure her food delivers, and the graceful way her bright, well-mannered prose captures the artist's fleeting delight. I may never make a cockle soup or taste the floral harmonies of strawberries laced with geranium cream, but as a summer city dweller who can sometimes hardly find the energy to peel the wrapper off a popsicle, I find it immeasurably entertaining to imagine the way David's revolt against the tyranny of frozen peas and "cold over-congealed lifeless food" must have stirred a shell-shocked populace still hard-wired to reach for the familiar and the safe and the convenient. Her humor, undiminished all these years later, still provokes ("The grotesque prudishness and archness with which garlic is treated ... has led to the superstition that rubbing the bowl with it before putting the salad in gives sufficient flavor. It rather depends on whether you are going to eat the bowl or the salad"); and her conviction that some meals -- like perfectly composed pictures -- could freeze a life's season in a decisive moment, still invigorates my heart.

I may not be charmed enough to possess an Edwardian picnic hamper of the sort that David details lovingly -- and I would certainly rather be on a hike in Wales than here in a sweaty room, shackled to my desk, sipping a lukewarm cup of coffee. But in the meantime, in this life in this summer in this city, I'm simply grateful that David did these things -- and wrote so gracefully about them. Whether read in bed in a baking tenement or at the breezy desk of a lolling barge, her words still ring like hypnotic prayers: "You are on holiday. You are in company of your own choosing. The air is clear. You can smell wild fennel and thyme, dry resinous pine needles, the sea. For my part, I ask no greater luxury. Indeed, I can think of none."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Gnocchi alla Genovese

Adapted from "Summer Cooking" By Elizabeth David

Serves 2-4

This is the recipe that cemented my ardor for Elizabeth David and seems to perfectly encapsulate both her insouciant humor and her insistence that simple dishes often result in the most amazing tastes. By way of introduction, David admits this dish is mainly "an excuse for eating pesto" -- and it has indeed proven a delicious way to dispose of the bushels of basil I have managed to harvest from plastic pots on my fire escape. Summer in this city may be full of shortcuts and deprivations but, thankfully, this meal isn't one of them.

Gnocchi

3/4 cup semolina flour

A pint of whole milk

A pinch of nutmeg, salt and pepper

1/4 cup grated Parmesan or Pecorino Romano

2 eggs

Season the milk with salt, pepper and grated nutmeg and bring to a boil. Pour in the semolina and stir until the mix becomes thick and smooth. Take pan off the heat. Stir in the cheese and eggs, then pour the batter onto a rimmed baking sheet, in a layer about 1/2 inch deep. Let cool in the refrigerator for at least 3 hours. Cut dough into small squares, and with floured hands, roll each square into a rounded shape. Lay the rounds on a floured board until all are prepared.

Pesto

1 big bunch of fresh basil

2 cloves of garlic

1/2 cup of pine nuts

1/2 cup grated Parmesan or Pecorino Romano

1/4 cup olive oil

Shred the basil leaves in a mortar and pestle or food processor, adding all the ingredients except the olive oil. As the pesto forms a chunky puree, add the oil a little at a time until the mix has the consistency of a smooth spread.

To combine

Bring a pot of water to a boil and drop in the gnocchi. Set aside an ovenproof dish. The gnocchi are done when they rise to the top of the pot (after three or four minutes). Drain and pour the gnocchi into the buttered ovenproof dish, mix in pesto and add a bit more butter and cheese to the top. Bake the dish in a 350 degree oven for about 10 minutes, until the gnocchi is bubbly and slightly crisp.

Allow to cool to warm room temperature. Pour a glass of wine. Turn on a fan. Eat.

Shares