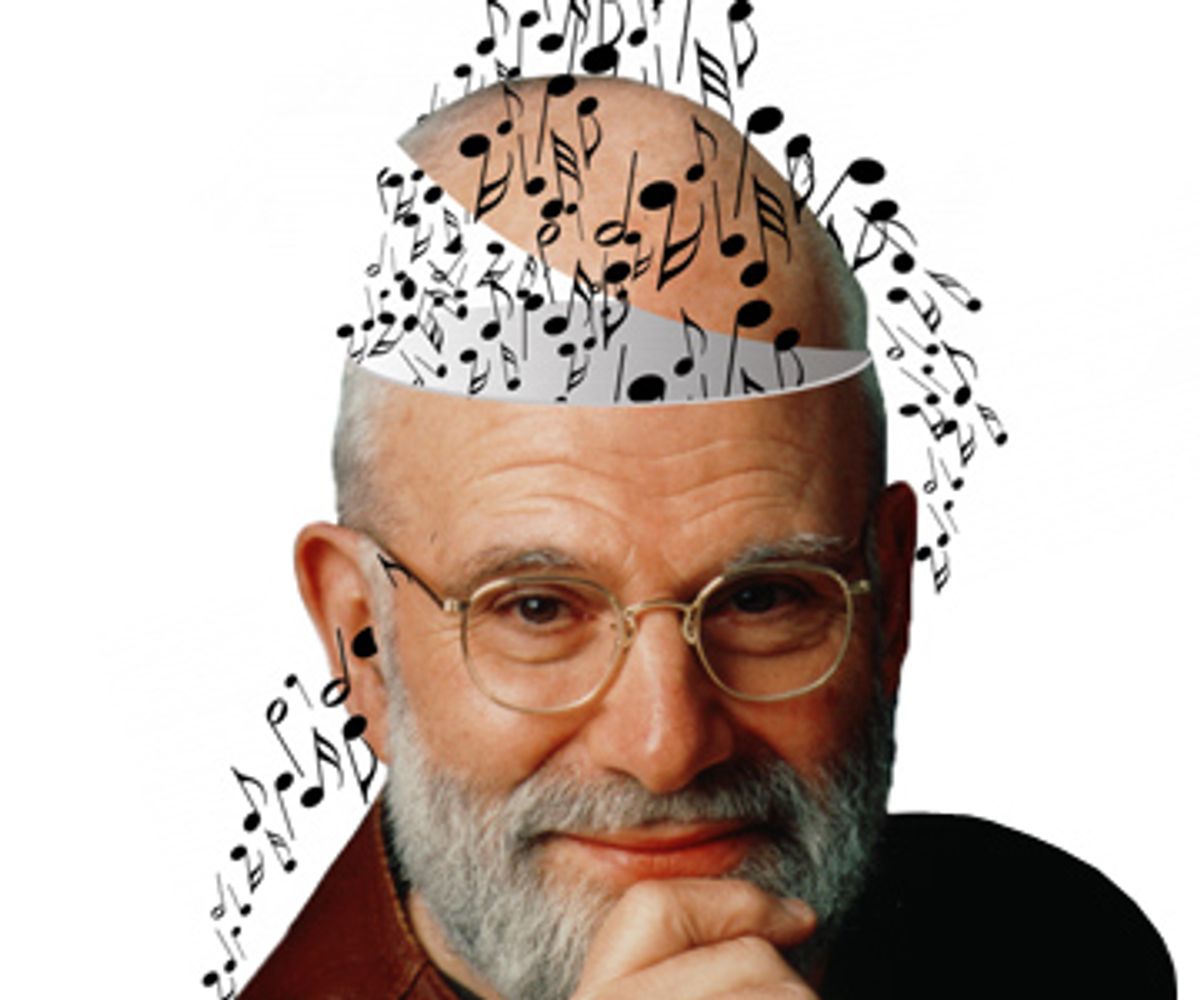

One essay in his new collection, "Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain," presents Oliver Sacks at his best, weaving neuroscience through a fascinating personal story, allowing us to think about brain functions and music in a bracing new light. "In the Moment: Music and Amnesia" follows an English musician and musicologist, Clive Wearing, who in his mid-40s suffered a brain infection that wiped out his memory and entire past. "It was as if every waking moment was the first waking moment," wrote Wearing's wife, Deborah, of her husband. But living in an eternal here-and-now is not Zen bliss for Wearing, it is "a never-ending agony."

With his characteristic empathy and keen eye for details, Sacks, a neurologist whose literary tales of his patients began appearing in the '80s in the New York Review of Books, and later in the New Yorker, wonders how Wearing managed to "retain his remarkable knowledge of music, his ability to sight-read, to play the piano and organ, sing, conduct a choir, in the masterly way he did before he became ill?" His answers delve into the brain anatomy where our trivial and emotional memories reside, and reveal the transformative power of music. Playing the piano or conducting reanimates Wearing, Sacks writes, and "engages him as a creative person." His performing self is "seemingly untouched by his amnesia, even though his autobiographical self" is virtually lost.

It's not entirely clear how Wearing can summon the delicate skills to play a Bach fugue, or that his conscious mind is involved at all. But Sacks doesn't leave the story hanging on a medical riddle. He lifts Wearing's story to a universal plane by explaining how music ignites our brains to express and reveal themselves: "A piece of music will draw one in, teach one about its structure and secrets, whether one is listening consciously or not."

In an amplified mental state, music erases the past and future. Time is always new. In that way, we are all Clive Wearing. "It may be that Clive, incapable of remembering or anticipating events because of his amnesia, is able to sing and play and conduct music because remembering music is not, in the usual sense, remembering at all," writes Sacks. "Remembering music, listening to it, or playing it, is entirely in the present."

That's a wonderful insight and explains why no matter how many times we hear the screen door slam, we still see Mary's dress wave as she dances across the porch as the radio plays. Unfortunately, Wearing's story is the only great song on "Musicophilia," which exposes the sentimentality and cursory science that unforgiving critics have always seen in Sacks' writing.

The book consists of 29 essays of various lengths that spotlight the ways that music rattles and hums in our brains. Focusing mostly on his brain-damaged patients, Sacks takes us on a medical mystery tour of musical savants, music therapy and "brainworms," those tunes that get maddeningly stuck in our heads. (Amid the recent news about the rogue security firm in Iraq, Blackwater, all I could think of was the damn Doobie Brothers.) He illustrates how symphonies and songs either enchant or taunt his patients who suffer from Tourette's syndrome, blindness, muscular disease and depression. As compelling as these subjects are, most of the book reads like Sacks' B-sides and outtakes. Many of the subjects make cameo appearances from his previous collections, "The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat" and "The Anthropologist on Mars." Even some of the science feels musty.

For all practical purposes, Sacks introduced lay readers to the mysterious organ in their heads. In his early books, by elucidating in clear and elegant prose the endless circuits of the brain, and how they electrify behavior, he demonstrated that only the tiniest neurological quirks separate us from the guy on the corner cussing out alarmed passersby. His greatest talent was bringing alive the individuality of his patients. Sacks showed us our humanity in books about biology. With the exception of Lewis Thomas, no physician has ever written better about his trade.

The problem with "Musicophilia" is evident from the first tale, which recounts the story of a musically disinterested doctor who in 1994 was struck by lightning. Not long after leaving the hospital, he becomes mad about Chopin. In no time, the doctor turns his life upside down to perfect the piano and compose music. Sacks has us jazzed to learn why the doctor's brain has turned him into Van Cliburn in waiting. We are primed to discover how the lightning-struck doctor might illuminate our own obsessions with Janacek or Coldplay.

After considering a couple of theories related to the arousal of the emotional centers of the brain, Sacks leaves us with no real insight into what sparked the doctor's musicophilia, conceding that the doctor never submitted to sophisticated brain tests. Sacks then concludes that the doctor's accident was "a lucky strike, and the music, however it had come, was a blessing, a grace -- not to be questioned."

It's admirable the doctor doesn't want to reduce his newfound sense of music and spirituality to damaged brain parts. But given that neurobiology could enlighten us about his condition, and Sacks doesn't, the story feels sentimental.

Some biologists have never been comfortable with that soft core in Sacks' articles. Sacks, they say, is the Ripley of neurology. Believe it or not, a man with visual agnosia mistook his wife for a hat! Believe it or not, a man with musical synesthesia sees blue whenever he hears music in D major! In a similarly sarcastic vein, Tom Shakespeare, a British disability-rights advocate, once labeled Sacks "the man who mistook his patients for a literary career." Richard Powers has a good time with that in his novel "The Echo Maker," in which he sends a character based on Sacks spiraling into an identity crisis by the fear that he has exploited his handicapped patients in his popular articles.

That sentimentality can be scooped out of Sacks' work is obvious in the gosh-darn awful movie of his book, "Awakenings." In the '60s, Sacks temporarily aroused long institutionalized patients from catatonic sleeping sickness by giving them mega-doses of the drug L-Dopa. The Hollywood version is all sap, no science.

Yet criticisms of Sacks' writing often sounds a tad shrill. At the top of his game, he has never exploited his patients but presented them with tremendous care. His most unforgettable article details the obsessive life of autistic adult Temple Grandin, an agriculture expert, who invented a humane ramp that leads livestock to slaughter. (Animals march to their doom on a curved chute, preventing them from seeing the grim cow reaper at the end of the line.) Describing the alienation she felt since she was a child, Grandin calls herself an "anthropologist on Mars." Sacks' long preface to the 1993 article has probably served as most readers' first primer on autism.

What may be working against Sacks now, at least against "Musicophilia," is time. Since the '80s, when his articles and books first became a buzz at dinner parties, neurobiologists have been the Ferdinand Magellans of science, mapping the brain in extraordinary detail. Good writers like Antonio Damasio and Gerald Edelman drill deeper than Sacks into brain anatomy, the lobes and the cerebellum, and their manifold functions. Readers have grown to expect a lucid explanation for nearly every neural spark of behavior, from romantic love to obsessive gambling. The deepening of neuroscientific literature has produced a new generation of anxious armchair neurologists.

When it comes to understand how music enters ours ears and lights up our emotions, the outright enjoyable "This Is Your Brain on Music," published in 2006 by musician and neuroscientist Daniel Levitin, reduces "Musicophilia" to permanent second billing. Levitin goes into compelling detail about why certain songs sound fresh after hundreds of listens. All tunes meld with the brain's "schemas," a web of memory connections that translate familiar things and situations into feelings. By upsetting the ingrained schemas with a simple twist in melody or rhythm, a good artist is responsible for that perennial spark of surprise. Levitin mentions Rachmaninoff, the Beatles and Miles Davis. Genetics be damned, the melody that snakes over the 16 bluesy measures of D minor 7 in Miles' "So What" is what makes the brain shine.

Sacks delivers his share of biological insights. It's stirring to learn about musicogenic epilepsy or "fear of music." (He doesn't mention if the Talking Heads borrowed the phrase for the title of their third album.) A case in point, Sacks writes, is "eminent 19th Century music critic, Nikonov, who had his first seizure at a performance of Meyerbeer's opera, 'The Prophet.' Thereafter, he became more and more sensitive to music, until finally almost any music, however soft, would send him into convulsions."

It's also intriguing to discover that people with perfect pitch have exaggerated "structures in the brain that are important for the perception of speech of music." Sacks doesn't bring it up but if we took an MRI machine back in time and photographed Mozart, maybe we'd see "an exaggerated asymmetry between the volumes of the right and left planum temporale." Ultimately, though, that wouldn't make or break our experience of the oceanic melody in the "Piano Concerto in C major."

Sacks is aware of this. In the beginning of "Musicophilia," he informs readers that he's not tapping the same vein of pedagogy as the recent staff of neurologists with fountain pens. "These new insights of neuroscience are exciting beyond measure, but there is always a certain danger that the simple art of observation may be lost, that clinical description may become perfunctory, and the richness of human context ignored," he writes. That's true. Human context is what makes good journalism, medical and otherwise. That's the art of Sacks' best essays.

For the most part, though, "Musicophilia" finds him caught between a concerto and a symphony. Human context is precisely what's missing from the short pieces. And the patients in the longer pieces seem like they could use a second opinion. Other than the story about Wearing, none of the essays synthesize a personal life, neurology and music into a sapient narrative. Perhaps Sacks senses that neuroscience is moving so fast that he's not sure where he fits in anymore, and he's trying his hand at this type of newspapery science reporting and that type of personality profile. More likely, he's clearing his desk of his miscellany, and capitalizing on the surprising popularity of Levitin's book.

In "A Leg to Stand On," his 1984 tale about trashing his knee while dodging a bull in the mountains of Norway, Sacks reports that repeatedly listening to Mendelssohn's "Violin Concerto" allowed him to regain "the natural rhythm and melody of walking." He replays the scene in "Musicophilia." To get his groove back, Sacks needs a new tune.

Shares