Every reader knows that the delicate emotional textures of a good book are the hardest things to re-create on film. Some filmmakers seem to know it, too: In adapting Brian Morton's sturdily exquisite 1998 novel, "Starting Out in the Evening," Andrew Wagner (who directed the 2004 feature "The Talent Given Us") may not get every nuance of the book exactly right. But it's rare to see a movie adaptation in which a filmmaker has taken so much care in translating the odd little qualities that make a particular novel special, to preserve the complex and fragile threads of feeling between characters that are often much easier to grasp on the page. "Starting Out in the Evening" is a small picture -- it was shot on location in New York City, in high-definition video, in 18 days -- but it's from a filmmaker who's used his brains to make up for any monetary resources he might have lacked. The picture feels both intimate and immediate, a model for what smart young filmmakers can do with good material.

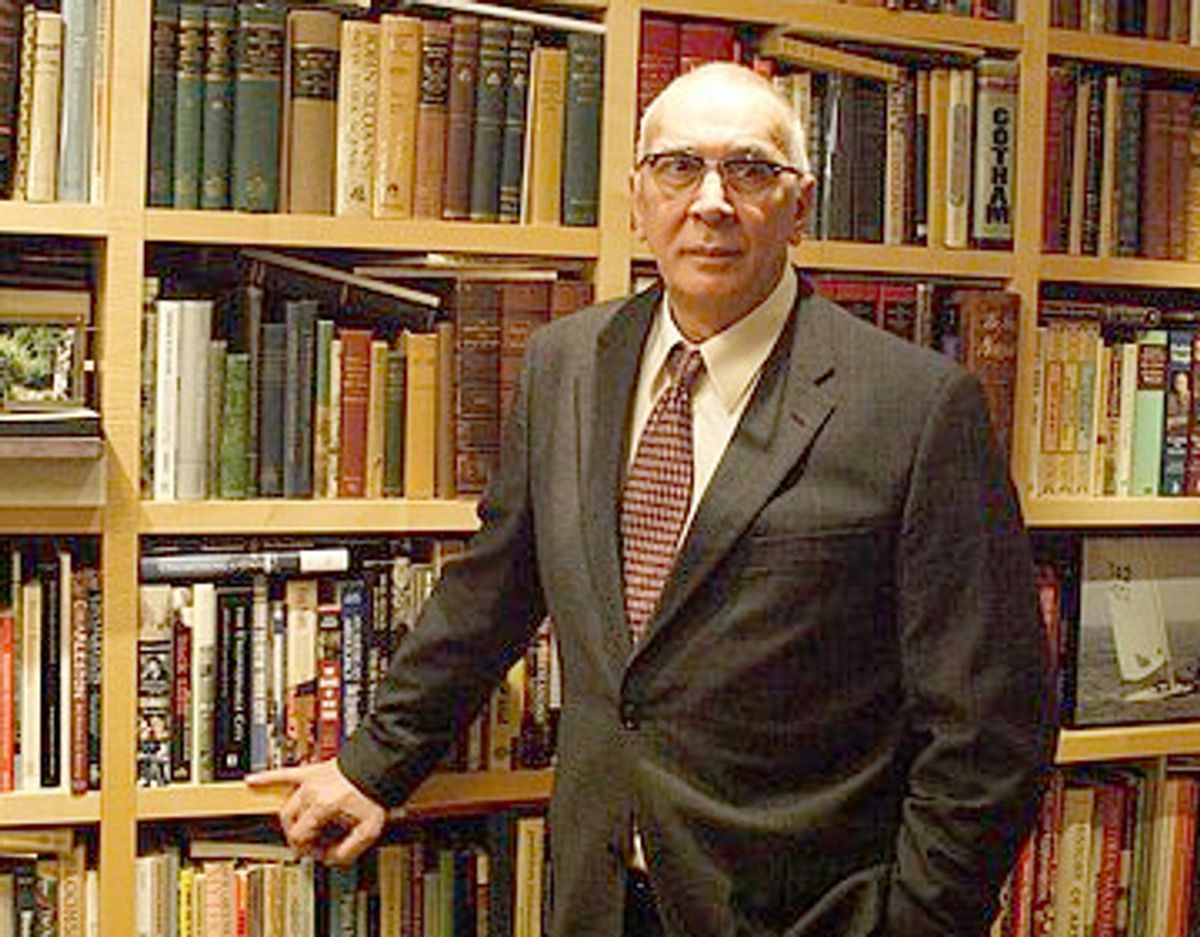

Frank Langella plays Leonard Schiller, a novelist in his 70s who has achieved moderate acclaim during the course of his career but whose books have drifted out of print. He's been working on his fifth novel for 10 years -- and this is real, old-fashioned work we're talking about, not coffee-shop laptop noodling. Leonard dresses for work, in jacket and tie, and sits down at the typewriter in his study for a specified number of hours each day. He's the kind of old-style writer, in the mold of Saul Bellow and (in his dedication to toil, at least) Norman Mailer, that was already becoming a dying breed when Morton's novel was published. Today -- particularly after the death of Mailer -- these men are even scarcer on the landscape, which gives the story a sharper edge of poignancy.

Leonard's life is changed when an ambitious 20-something graduate student named Heather (Lauren Ambrose) approaches him: She wants his work to be the subject of her thesis. (One of the loveliest qualities of the story is the way it asserts that a life can be changed even when a person has reached his 70s.) Heather wants his approval and his participation (and possibly more), and she's convinced her research will spark a rediscovery of his work. Leonard demurs, but he finds the attentions of this attractive, intelligent young woman difficult to resist. Leonard's daughter, Ariel (Lili Taylor), a former dancer who's nearing 40 and longing for a child -- she's on the brink of renewing a relationship with an old flame, played by the wonderful Adrian Lester, who doesn't share her desire for children -- is puzzled by the unusual bond that has begun to form between Heather and her father, but she resists passing judgment on it. Still, her own relationship with Leonard has always been complicated and a little prickly: Her mother, Leonard's wife, has been dead for some 20 years. Although Leonard clearly loves his daughter, over the years he's poured more emotional energy into his work than he has into his relationship with her, for reasons that are purely human: Words are so much easier to manage than people are.

Wagner -- who wrote the screenplay with Fred Parnes -- sees that this is a story with no villains, although the threat of emotional treachery is always vibrating in the margins. His actors are all beautifully in tune with the material and with one another. Ambrose gives a very fine and terrifying performance: Even though there's an inviting roundness about her, her dark, glittery eyes suggest a calculating hardness. When Leonard takes her to a party filled with literary stars, she immediately dashes from his side to make a beeline for a powerful editor (played by Jessica Hecht), boldly ingratiating herself in a clear bid to get some work out of the woman. Even so, as Ambrose plays her, Heather isn't wholly unsympathetic -- she doesn't know how to control what she's started, simply because it's uncontrollable. She's a young person who has allowed herself to be guided by impulse and ambition rather than compassion.

Taylor also gives a wonderful performance here: Her Ariel has a breathless, open-hearted quality that makes you want to protect her, but she's not a sap -- the mistakes she makes are the normal ones any of us might make in figuring out what we want out of life and how to get it. She also carries the movie's most beautiful and most wrenching moment, one that I suspect will resonate with any adult who has ever lost, or faced the possible loss of, a parent.

Langella carries the weight of Leonard's mistakes, achievements and missed opportunities on his tweedy shoulders. This is a lovely, fine-grained performance, the sort of role an aging actor is lucky to get, but also one that demands a great deal of surefootedness and sensitivity. Early in the picture he stares at his new young friend with wide, unblinking eyes, as if she were a creature from Greek mythology sent to the here-and-now to confound and test him. Later, as he warms toward her, his cautious openness is heartwrenching. For years now, white male writers -- the old-style kind, like Leonard -- have been out of fashion. These are the kinds of guys we're never supposed to identify with, as punishment for the fact that their view of the world was once treated as supreme. "Starting Out in the Evening" suggests, among other things, that once these writers have disappeared, we'll have lost more than we know. Someday their books will be in style again. Until then, there's no law against feeling something for them. Understanding the human heart is an equal-opportunity affair, and old -- or even dead -- white guys have often done it as well as anybody else.

Shares