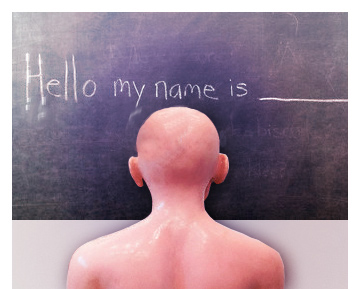

Hollywood loves amnesia. From “Spellbound” to “The Manchurian Candidate,” “Memento” to “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind,” “Mulholland Drive” to wonderful old sci-fi epics like “The Alligator People,” somebody is always losing his memory in movies. No matter how good or bad, these films share one powerfully seductive quality; being fictitious, they allow us to suspend our disbelief in the biological plausibility of amnesia in exchange for the romantic notion of erasing our pasts. They allow us to feel what it would be like to recover lost and cherished memories, or to establish an entirely fresh identity from new or even implanted memories.

But how are we to look at fictitious amnesia presented as factual truth? That question has been haunting me for weeks, ever since I rented the 2006 documentary “Unknown White Male.” On the film’s official Web site, director Rupert Murray introduces his film as the “startling story of Doug Bruce, a man who, for no apparent reason, lost 37 years of life history, who lost every memory of his friends, his family and every experience he had ever known. This true story follows Doug in the hours and months following his amnesia, as he tries to piece his life back together and has to discover the world anew.” When the film was first released, it received mostly positive reviews. Roger Ebert called it “an intriguing and disturbing film.” Some critics, on the other hand, sensed that it was a hoax.

After having viewed the movie twice, and interviewing Murray, I have little doubt that the movie was made in good faith. Yet Bruce’s condition is medically implausible. To me, the real attraction of the movie is that it transforms a viewer into an armchair neurologist, forced to diagnose a bizarre memory loss that has stumped the experts. I cannot imagine a better medical training film for sorting out a neurological from a psychiatric disease, for determining whether a patient’s condition is real or imagined.

When we meet him, Bruce is a retired British stockbroker and photography student living in New York City. One day in 2003, he suddenly awakens on the subway to Coney Island, completely stripped of his past; he doesn’t even know his own name. He does complain of bumps on his head and a headache, but he isn’t aware of having been mugged. Bruce begins his adventure by walking into a police station to seek help. After a series of tests, including MRI and CT scans, reveal no related physical problem, Bruce is hospitalized on the Coney Island Hospital psych ward. The name that a nurse enters in his chart is Unknown White Male. He has no identification but does have a slip of paper with a telephone number, which conveniently leads to a former girlfriend.

Bruce’s reimmersion into daily life and into his past is filmed by Murray, an old friend of Bruce’s from London and a budding filmmaker. To aid viewers in his journey of self-rediscovery, Bruce provides Murray with his own video footage that he began shooting within a week of losing his memory. Included are conversations with the camera, shots of him returning to his Greenwich Village loft and even his airport reunion with his father and sisters, neither of whom he recognizes or remembers. Describing his first encounter with his father, Bruce said, “My father is not at all what I expected.” The viewer is left to ponder how someone without a memory of his father would have expectations of what he would be like.

To understand Bruce’s amnesia, imagine how you’d think and act if you had completely lost your personal identity. You’d be sunk in profound terror and confusion. Without a personal background and sense of self, what could you do? What would you want to do? Without a significant fund of prior knowledge about the nature of the world, you would neither understand your confusion nor know what future steps to take to sort things out.

This raises the first serious problem with Bruce’s story: Imagining future actions requires past knowledge. In an April 2007 article in the journal Neuropsychologia, a Harvard research team headed by psychologist and memory expert Daniel Schacter suggests that the primary role of memory might not be for reminiscence but rather to facilitate thinking about the future.

In a series of fMRI studies, healthy young volunteers have shown similar areas of brain activation when thinking about past personal memories and when imagining themselves in future events. The Harvard researchers state that “there is no adaptive advantage conferred by simply remembering, if such recollection does not provide one with information to evaluate future outcomes.” Supporting evidence for their conclusion is a vast body of neurological literature documenting that patients with damage to areas of the brain vital for laying down past memories have impaired ability to elaborate future scenarios. So, to the extent that one is stripped of one’s past, one is cut off from one’s future. Conversely, to the extent that one’s behavior suggests some understanding of a future, one must not be entirely cut off from one’s past.

For Bruce to turn himself in to the police implies some knowledge that the police might be helpful — a scenario that requires access to prior knowledge of how police behave in general. To carry around a video camera and film his meetings with “old” friends and family, Bruce would have to have some understanding that there was some future value to shooting the film. Without a recollection of his past, he wouldn’t be able to project when and where such a movie might be shown, or even who might want to see it. Similarly, in an article that questioned the veracity of the film, the Washington Post asked why Bruce, only days after the incident, registered the e-mail address Unknownwhitemale@yahoo.com? How would Bruce understand that this address might be of future value?

During a phone interview, Murray explained to me that Bruce lost his personal (episodic) memories, but retained his semantic (impersonal factual knowledge of the world, such as that a Chevrolet is a type of automobile) memories. In large part, Murray bases this distinction on his interpretation of the writings of Schacter, as well as on Schacter’s discussion of episodic and semantic memory in the movie. But there’s more to situational memory than this arbitrary distinction. Knowing the dictionary definition of police isn’t sufficient to predict how the police might or might not respond under a wide variety of circumstances, or even if they can be trusted. Think of the complicated and even contradictory impulses you have when someone in a bar suddenly hollers out, “Call the police.” Everything from your past experience to geographic location colors your understanding of the word police.

In the movie, Murray refers to Bruce’s amnesia as representing a fugue state, a psychological condition of no known cause in which one temporarily (for days or weeks) loses all sense of self. But Bruce’s amnesia has persisted to the present. Murray is now unwilling to pin any specific label on Bruce, telling me that none of the experts was able to provide a final diagnosis. In his interview on camera, Schacter suggests that Bruce’s memory loss falls into the category of functional or psychogenic amnesia — two interchangeable terms used to describe a condition of profound loss of past memories, unassociated with any impairment of new memory formation and not explainable by any known medical illness. Schacter affirms that, in the case of Bruce, there isn’t any available scientific evidence to explain how such a profound amnesia might have occurred.

In their daily practice, neurologists most commonly confront acute memory loss in a syndrome known as transient global amnesia (TGA). Occurring primarily in healthy people over 50, the specific cause isn’t known. The most popular explanations are that there is temporary interruption of the blood supply or an electrical “short circuit” in the regions of the temporal lobe that process and store new and retrieve old memories. Typically, such patients are acutely confused and disoriented; they have great difficulty creating new memories (anterograde amnesia). Their inability to recall old memories (retrograde amnesia) can extend back 10 to 20 years prior to the episode. But it is never complete. In the most thorough study of patients in the throes of an acute TGA attack, UC-San Diego neuroscientists demonstrated that a significant amount of apparently lost personal memories could be retrieved when the examiner asked more probing questions about the patients’ pasts. Another hallmark of memory impairment in TGA patients is that they — unlike Bruce — do not forget who they are. Personal identity is uniformly retained.

Even in patients with chronic amnesia resulting from severe brain injury, alcoholism or encephalitis, retrograde amnesia isn’t total. More recent memories are affected more than remote memories. A patient might lose months or even years of his memory immediately preceding his brain insult, but memories from long ago — greater than 10 to 20 years — tend to be preserved. By the time retrograde memory loss is total and all personal identity is lost (as with the profoundly demented), patients have become completely helpless and unable to take care of their most basic needs. I’m not aware of a single well-documented case of a patient who suffered a complete loss of personal memory while able to accurately lay down new memories.

If a neurological explanation for Bruce’s memory impairment is out of the question, is there any justification for a psychological cause? Although the movie offers no specific instance of psychic trauma, it repeatedly mentions that Bruce’s mother’s death from cancer a few years earlier may have been the triggering emotional event.

Even so, we are faced with the same problem: Emotional trauma must ultimately work by changing brain chemistry. If you get depressed and forgetful after the death of a close family member, the triggering event is purely psychological, but the depression and forgetfulness result from neurotransmitters such as serotonin going haywire. With memory impairment from post-traumatic stress disorder, elevated levels of stress hormones such as cortisol can be found, as can MRI evidence of reduced hippocampal volume, the part of the brain responsible for processing and storing new memories. In other words, psychic trauma plies its undesirable effects through physical brain changes. But there is no evidence linking physical changes with psychologically induced amnesia, either in Bruce or in the neurological literature.

In the absence of hard scientific evidence for psychogenic amnesia, neurologists might expect to find some epidemiological evidence for it. They might expect to see it among survivors of concentration camps, 9/11, the Columbine massacre or airplane crashes. Yet this isn’t the case. There isn’t a recognizable clinical syndrome in which high-stress survivors forget who they are. Instead, many suffer from not being able to forget. As Holocaust survivor Jorge Semprun wrote in his extraordinary memoir, “Literature or Life,” getting on with life required a constant effort to forget; he called it “a studied amnesia.” A 1998 review of psychogenic amnesia in the British Journal of Psychiatry failed to find any convincing data that could demonstrate psychogenic amnesia following major emotional trauma.

That brings us face to face with a fundamental question raised by “Unknown White Male”: Is psychogenic amnesia a real medical condition? Part of the problem is that there is no definitive test to prove whether a patient is actively faking or truly experiencing memory loss. If we knew the exact fMRI patterns for “true” and “feigned” amnesia, and a patient unequivocally demonstrated the “feigned” pattern, the patient could always argue that such findings only represented unconscious brain activity of which he was blissfully unaware.

In 1986, Schacter argued that “there are few well established facts regarding the nature of simulated amnesia, and no evidence that experts can distinguish accurately between genuine and simulated amnesia.” By 1999, only a third of 300 board-certified psychiatrists polled felt that psychogenic amnesia should be included without reservations in DSM-IV (the psychiatric diagnostic manual); only 25 percent felt that the diagnosis was supported by strong scientific evidence. By 2006, psychiatrists from Johns Hopkins and Columbia-Presbyterian medical centers concluded that psychogenic amnesia “remains best conceptualized as a relatively rare form of illness-simulating behavior rather than a disease.”

So is Bruce’s simulated amnesia a pure scam for financial gain or, as some have suggested, a bid for celebrity? Is it the reflection of a serious mental illness (factitious disorder), in which patients feel an inner need to be seen as ill or injured? Perhaps. But even this dubious psychiatric distinction can only be based on guesswork about what Bruce is experiencing.

Like most movie reviewers, I am satisfied that Murray’s intentions for making the movie were straightforward and legitimate. Indeed, Murray’s thoughtful conversation echoed much of the psychiatric literature on the origin of simulated disease. Referring to the possibility that Bruce’s amnesia was a hoax, Murray said, “There is no empirical data one way or the other.” He told me that none of Bruce’s many diagnostic tests, including standard MRI and fMRI, showed any convincing reason for the amnesia. Neither did Bruce’s visits to multiple psychiatrists. “At the end of the day, all you can go on is your own personal experience, your own personal intuition,” Murray said. “Who knows what happened. Maybe at some point in his mind he did want to become someone else. I really don’t know.”

Knowing that Bruce’s amnesia was likely feigned, either consciously or unconsciously, I watched the film a second time. Again I was swept up in the story. It was as though I wanted to believe, even when I knew better. This is exactly the draw of the movie. Bruce’s story taps into a universal desire for a fresh start — the tabula rasa upon which we can rewrite our life history. Here’s Bruce, magically and without explanation, accomplishing what most of us only dream of: neutralizing the bad memories that make our pasts into emotional minefields. He validates our deepest desire to believe that the mind is sufficiently powerful to overcome its own obstacles and begin anew. He shows us that despite what science may say at a given time, it may never be the full explanation, giving each of us full license to believe in the veracity of wildly implausible human behavior. “One of the unique aspects of brain disorders is that there are endless unique cases in science, and seemingly the unexplainable become explainable later on,” Murray told me.

In his review of “Unknown White Male,” Ebert asked, “Is that person any more or less real to us if the film is truthful or fraudulent?” The overriding issue raised by the movie, though, isn’t scam or fraud; it’s about how certain psychiatric conditions exist solely as reflections of how we interpret human behavior. In a question-and-answer session among Murray, the film’s producer, Beadie Finzi, and a movie audience, included on the DVD, Finzi summarized her conviction that Bruce’s amnesia is “true” by saying, “The facts are that everyone who does know him, who has ever known him, is completely convinced that this has happened.” Although Schacter and others have already shown that there is no decent method for distinguishing simulated from genuine amnesia, the filmmakers, most of Bruce’s former friends, and most viewers and movie critics believe that Bruce’s amnesia is “real.”

For me, the most startling consequence of the movie is that so many are willing to put aside the present-day neuroscience of memory in favor of relying upon gut feelings and personal experience. This is hardly a sound approach to categorizing psychiatric disease, and yet this is precisely the logic that has perpetuated the myth of psychogenic amnesia as a bona fide medical condition.

The movie is a powerful reminder of how other simulated medical conditions — such as Munchausen syndrome, in which patients injure themselves to gain attention and emotional support — are often overlooked or denied by friends and family, and even some doctors, precisely because they trust their gut feelings rather than prevailing medical evidence. These patients often embark on extended medical pilgrimages, going from doctor to doctor, hospital to hospital, convinced that they are misunderstood patients who only want to get better. This may apply to Bruce, although, sadly, he may not be aware of it. The failure to recognize simulated illness is a commonplace medical error with often tragic results, ranging from broken families to serious self-generated diseases and utter disruption of a patient’s life.

In the end, “Unknown White Male” is a true story of a simulated illness. But when it comes to Bruce’s amnesia, it is only a movie.