I had my first heart attack when I was 18. I was striding across campus when it hit, like a bomb going off in my chest. My left arm went numb, and it got harder and harder to breathe. I was used to being sick — by the time I started college, I’d already had skin cancer, meningitis, pancreatitis and blood poisoning — but this was a whopper, and I was knocked over by the crushing pain. This was different. This could kill me, kaboom, right there on the quad.

I had to get to a hospital. I still don’t know how I got to the student clinic, how I got across the campus and up the stairs, but I did. I staggered through the double doors and collapsed into a chair.

“I’m having a myocardial infarction,” I gasped, when I was finally ushered into an exam room. “Heart attack,” I added, when this failed to produce a crash cart.

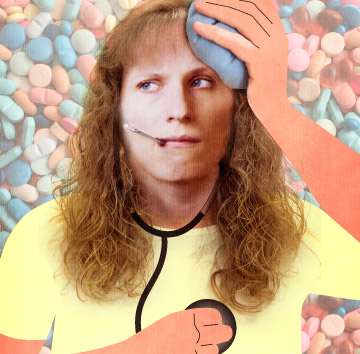

“I know what a myocardial infarction is,” the nurse said, casually taking my vitals. “You’re not having one.” She pressed a stethoscope to my chest.

“Well, it could be a stroke,” I conceded.

“You’re not having a stroke.”

“I think we should run some tests.”

“Haven’t we seen you in here before?”

“Once or twice.”

The nurse stood up and placed her stethoscope in her pocket. “You’re fine,” she said. “Your vitals are normal. You’re a perfectly healthy 18-year-old girl. I promise you’re fine. Go out, take a walk. It’s a gorgeous day and you’re not dying.”

It was a gorgeous day, and I wasn’t dying. I’d been spared, by fate or just dumb luck. This, too, had happened many times before. The skin cancer turned out to be ballpoint ink; the meningitis, hay fever; the pancreatitis, too many candy bars; the blood poisoning, ill-fitting shoes. I did not have lupus, multiple sclerosis, Huntington’s disease or Hodgkin’s, Crohn’s disease, diabetes, myelitis or muscular dystrophy.

What I did have was hypochondria, which meant that every other disease was inevitable. I might have escaped the heart attack and the Hodgkin’s, but surely something serious was only a matter of time. I could not leave well enough alone, and once dengue fever was ruled out I would return with malaria. There were just so many diseases out there, all strange and for the most part unavoidable. There was, for instance, foreign accent syndrome, the bizarre but real neurological condition that transformed native West Virginians into Eliza Doolittle overnight. There was pibloktoq, a seizure condition common to Greenland Eskimos that compels them do things like destroy furniture, disrobe, scream obscenities, and eat feces. There was SUDS, the mysterious disorder that claimed healthy young Asian men in their sleep, and even though I was neither, my father had been born in China, so who’s to say I couldn’t catch it from him.

You could catch lots of things. Maybe you’d get paragonimiasis, and parasites would eat you; or you’d get pica, and you’d eat them. Anything was possible.

It’s hard to say when the hypochondria started. I’d been worried about my health for as long as I could remember, the anxiety growing like a tumor, each year introducing a new way to die. There were so many ways to go. Besides diseases there were poisons everywhere you looked. A whiff of the wrong fumes and you’d have instant brain damage. Mistake the glass cleaner for Kool-Aid, and who wouldn’t, they were both blue, and you’d need a new liver. By age four I knew to avoid the skull-branded bottles under the kitchen sink, but what about natural toxins? The local landscaper had thoughtfully mined the front yards of our family-friendly neighborhood with all manner of poisonous plants. My parents had warned us to steer clear of the oleander and holly berries, but sometimes a brush was unavoidable. What if I forgot and stuck my pollen-coated fingers in my mouth? What if I sneezed, open-mouthed, and a gust of wind blew a blossom in? It didn’t seem likely, but it was possible, wasn’t it?

The scariest plant of all, of course, was the family tree. When a fourth-grade assignment required me to compile my own I took less note of when ancestors died than what of: did we have a lot of heart disease in our family? Any lupus? MS? How about Hodgkin’s?

There was remarkably little cancer, it turned out. Hypochondria, however, was in ample supply. The tendency to fear the worst was right there with our short legs and big feet. I had relatives who couldn’t breathe, and others who couldn’t swallow, and a number who suffered from vague, lingering conditions that required me to forfeit control of the television when they came to visit and to please not wear the loud shoes. There was the musician who was more adept at what doctors dryly call the “organ recital,” the litany of abstract complaints that is the hallmark of the hypochondriac.

My favorite hypochondriac was a cousin thrice removed who was convinced she had stomach cancer. Sure she was dying, she was too afraid to go the doctor until the pain became completely unbearable. Her stomach tumor was born six hours later. He weighed seven pounds, and they named him Francis.

Who knew what bombs were ticking inside you. Even if you didn’t inherit any of the awful genetic diseases you could always catch something: Ebola or malaria, hepatitis or TB. You could pick up a virus, an environmental disease, an infection or a parasite. And then there’s the endless list of worms, thousands upon thousands, crawling in and crawling out: fluke and flatworm, beef worm and tapeworm, roundworm, pork worm, threadworm, heartworm, hookworm. Worms surpass us in both number and fortitude; several thousand nematodes aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia survived the crash. Worms will certainly eat you when you die and perhaps well before. Pinworms might invade your rectum; flatworms, your bladder; guinea fire worms might consume your flesh from the inside out. It could happen. It’s been happening for eons. The guinea fire worm, in fact, is what you see in the caduceus, wrapped around the rod. Healers used to slit the skin open and draw the critter out with a stick. Yes. Gross.

Hypochondria is no less disturbing and almost as old. It has existed, in various forms, for thousands of years. Perhaps because it allows you to lie in bed without actually killing you, it has endured and flourished and was taken quite seriously for most of history, enjoying a true heyday in the 17th and 18th centuries. By the 19th century it had started to acquire the stigma it retains to this day. It had become perceived as largely untreatable. It was too physical for psychotherapists, too mental for medical doctors, and it responded poorly to treatment of either kind. What was the point in caring for a patient who wasn’t sick, but who would never get better nonetheless? And who wasn’t even crazy in a fun way? At least with paranoid schizophrenics you get good stories. But unless you find the symptoms of colon polyps interesting, hypochondriacs are just a bore. There’s no glamour in it, no red-carpet charity fundraisers for it, no celebrity spokespeople. And you couldn’t ask for a worse poster boy: its most famous sufferer was Hitler.

Even doctors hate us. Most doctors would rather see a patient with suppurating genitals than a hypochondriac, and with good reason. Hypochondriacs are difficult, doubting backseat doctors who continually second-guess their physicians. Convinced that something is fundamentally, fatally wrong, they are the patients who are angry when the path report comes back benign. They are also outrageously expensive. It’s estimated that they cost healthcare providers billions of dollars in unnecessary tests, care, and procedures.

The problem, of course, is that sometimes hypochondriacs really do get sick. I do, in fact, have about a million things wrong with me. Besides the hypochondria, which makes me think I have everything, I have a long list of very real syndromes and conditions, and the reason I’m so uncomfortable in my body is, in part, because it’s such an uncomfortable place to be. I’ve had just about every annoying condition that doesn’t actually affect your overall health: the nuisance diseases. There’s the OCD and the IBS. There are the transient parasthesias, where random parts of my body go numb for no reason at all. I’ve been afflicted with eczema and allergies; appendicitis, gingivitis and tendonitis; carpal tunnel syndrome, Bell’s palsy, essential tremor, heart irregularities, macromastia and hypoglycemia. I have skin conditions that make me prone to other skin conditions, and have been treated for scabies three times and ringworm twice in the last three years. I’m legally blind in one eye. I also have really bad hair, and cannot for the life of me understand why Japanese hair straightening isn’t a covered benefit.

In spite of all this, I’m essentially healthy. Other hypochondriacs aren’t so lucky. Some have the misfortune of being both hypochondriac and sick, and sometimes patients who get dismissed as hypochondriacs turn out to be profoundly ill. My father, a surgeon, had a patient whose endless, baseless complaints were vindicated a long time later when new technology finally revealed a well-concealed tumor. Researchers are starting to think that one of the most famous hypochondriacs, Charles Darwin, was not a hypochondriac at all, but was suffering from a never-diagnosed case of Chagas’s disease, a debilitating tropical parasitic disease that wreaks havoc on the heart and nervous system. It’s theorized that both Nietzsche’s and Howard Hughes’s hypochondria and general weirdness may have actually been caused by end-stage syphilis. In Key West, a lifelong hypochondriac got the last word when she dropped dead at age 50. Her tombstone reads, “I TOLD YOU I WAS SICK.”

But most hypochondriacs are just whiners. It’s this endearing quality that has earned us a number of unflattering nicknames. In the medical industry we are known as GOMERs (Get Out of My Emergency Room) and turkeys. Because we are also known as crocks and crackpots, physicians will sometimes order a check of our “serum porcelain level.”

The more sensitive call hypochondriacs the “worried well.” The name is apt. We do, indeed, worry extremely well. We worry consummately and constantly. Hypochondria is, in its own way, a terrible disease. The Merck manual gives it a 5 percent cure rate. This means that you are far more likely to recover from leukemia, heart failure, or necrotizing fasciitis than hypochondria. A few sufferers have even died of it, most notably the writers Sara Teasdale and Jerzy Kosinski. Both committed suicide when they feared death, by nonexistent illness, was imminent. Cancer, genetic defects, rare disorders — hypochondria makes every condition contagious. For me, transmission usually occurs through the television. They mention it on the news, and within a few hours I’m pretty sure I have it. A hypochondriac family friend was a champ in this department. Kennedy’s back problems, Johnson’s gallbladder disease — he had them all. When Babe Paley and Betty Ford were diagnosed with breast cancer my mother was sure he’d have his own biopsy scheduled within days. He didn’t, but he did catch Nixon’s shingles, and most surprising of all they turned out to be real. Recently, it’s become more common for transmission to occur through the internet. The proliferation of medical websites has produced a new variant of the disease called, predictably, “cyberchondria.” It’s becoming increasingly prevalent, as the number of people searching for health information online has gone up dramatically. And some of us are responsible for more than our share of hits. (To qualify as a cyberchondriac, you have to visit a health site six times a month, a number I can hit easily during the commercial break of “Trauma: Life in the E.R.”)

This new digital form of hypochondria presents new problems. The web is loaded with the sort of bad medical advice that led me to treat one rash with a diet of all orange foods and another with direct applications of toothpaste. Many sites seem designed to enflame the alarmist, with symptom finders that quickly escalate from stuffy nose to sinus tumor.

Today, for instance, I’m in pretty good shape. There’s a weird mass inside my cheek, my finger hurts, and my hamstrings are sore. I have a rash on my feet and a mild headache. Twenty minutes on the internet revealed that I do not have deep vein thrombosis, as I suspected, but I still have plenty to worry about: it appears that I do have bacterial meningitis, and that it’s too late to do anything about it. Still, this is a blessing, because it’s a faster way to go than the oral cancer that would take me if that cheek lesion were allowed to run its course.

It would be a shame to die now, though, just when hypochondria’s reputation is starting to enjoy a boost. In the past few years the stigma has eased just a bit. Perhaps driven by the outrageous costs of treating people who aren’t really sick, the medical industry has begun to reevaluate the condition and has come to view hypochondria as a disease in its own right, just not one that requires MRIs, exploratory surgery and kidney donation.

It’s hard to say what is behind the change. The web may have something to do with it, easing the exchange of information. Money is part of it, too, as HMOs look for ways to cut costs and please patients. Patients aren’t patients so much as consumers now, and the customer is always right, even if the customer is insisting that the sore muscle is end-stage liver cancer. Or it may just be greater acceptance of neurotic behavior in general. Hypochondria is, in a way, just a logical extension of a larger trend toward self-care, like taking vitamins or getting elective coffee enemas.

Coffee may, in fact, play a role. The last time hypochondria was taken seriously was during the Age of Enlightenment, when hypochondria was both common and chic. Then, as now, coffee was also wildly popular, and it does seem worth nothing that caffeine is a drug that induces both palpitations and manic self-examination.

In the last 20 years hypochondria has been renamed “somatoform disorder,” which is more descriptive of the disease as it’s understood today — a condition in which you translate stress, or unhappiness, or too much free time, into actual physical symptoms. The common perception of hypochondria as a condition in which a perfectly healthy person worries himself into a lather over nothing isn’t quite right. He’s worrying himself into a lather over something that turns out to be nothing. The pain and symptoms are real; they just have no underlying cause.

It sure seems like they do, however. Hypochondria is very different from faking sickness to get out of work or military service, and it’s not a variation of Munchausen’s, where the patient knowingly fakes illness to get attention. Hypochondriacs think they’re sick because they really, really feel sick, with symptoms they can’t ignore: shooting pains or numbness, hair loss and rashes, fevers and palpitations. It’s amazing what the mind can produce. Expectant fathers suffering from a somatoform condition called Couvade’s syndrome acquire all the symptoms of pregnancy except the actual fetus: morning sickness, weight gain, cravings, even labor pains.

The good news is that somatoform disorder is fairly treatable. Hypochondria is an expensive disease, but once you stop treating the phantom brain tumors and start treating the hypochondria itself it becomes very cost-effective. Recently it’s become clear that cheap treatments like cognitive behavior therapy and Prozac will usually do the trick. CBT works about half the time, and SSRIs, about 75 percent. And if not more effective, they are certainly more fun than 17th- and 18th-century cures, which leaned toward enemas and worse. John Hill’s 1766 I’ll-give-you-something-to-cry-about prescription is particularly unpleasant: You’ll stop fretting over your imaginary aches and pains, he argues, if you develop honest-to-goodness scurvy, and your bleeding hemorrhoids won’t worry you at all once you catch leprosy.

In the past year, I’ve gotten much better. There was exactly one doctor visit, for a very real and completely gross sebaceous cyst. Though I still surf from time to time, I no longer have WebMD bookmarked; and while it’s true that I received both a Physicians’ Desk Reference and Stedman’s Medical Dictionary for Hanukkah, I mostly use them to diagnose other people.

I’m not entirely sure why things improved. Maybe my hypochondria responded to CBT and SSRIs, or maybe it responded to HBO and MTV — I got really, really great cable, and this has proved a wonderful distraction.

And this, I realize, is part of it. John Hill was right: you don’t notice the bleeding hemorrhoid when you get leprosy. You don’t notice the boredom and depression and the fear that your life is completely off course when you have a funny twinge to preoccupy you instead. And you don’t notice the funny twinge when Meredith Baxter Birney is fighting off both alcoholism and would-be kidnappers on the E! network.

I’m particularly fond of the medical shows. Because I’m still susceptible to infection by TV, I tend to favor shows about conditions I’m unlikely to get: dwarfism, gigantism, inguinal hernias, or that genetic anomaly where you grow a full head of hair on your face.

Just now I noticed a little, pinkish pocket of fluid under my eye. It could be an infection, I suppose, or maybe something deadly bit me in the night. And I could spend the rest of the morning on the Web, on the phone with my doctor or my dad, trying to figure out what it is, and how long I have left. But at eleven The Learning Channel has a special on the morbidly obese, followed by eight hours of maternity ward emergencies. After dinner, I’ll watch a show about Munchausen moms and another about cataplexy, then go to sleep by the light of plastic surgery disasters.

I’ll probably be just fine.