On a moonless summer night my husband fell 10 feet from a sleeping loft to the floor and did not die. He did not die, though he was 75 years old, and the accident happened in a remote seaside cabin inaccessible by road on a coastal island with no doctor on call, much less a hospital. He did not die, though X-rays taken several hours later showed that he had broken most of his ribs and both feet, punctured both lungs, causing perilous internal bleeding, and suffered so many blood clots in his brain that each CAT scan of that precious organ resembled an elaborate filigree.

After four weeks in the ICU, Scott traded the breathing tube for a “trach collar,” a device connected to the respirator, which was surgically inserted directly into his windpipe and contained a hole for a speaking valve. The first words he uttered, pointing to the sink: “Kleenex, please.” Like a child’s first word, a triumph. Thrilled and grinning, I handed him the small box of tissues. He wiped his nose. Immediately my grin faded, as out of his mouth poured a great torrent of words, some comprehensible, some not, a wild river of stories, mixing events I knew about with some I never heard of in our 20 years together. One by one the doctors and nurses drifted into Scott’s room to witness the miracle and assess the damage. They questioned him closely to see what he knew of the past and present. He knew his name and the date and city of his birth, but he didn’t know the current year, month or season. He knew that my birthday was in August, but he couldn’t remember my name. He knew we were in Maine but thought the city we were in was San Francisco. He remembered that at age 18 he left Cleveland for Duke to study biology, chemistry and physics, but he claimed to have gone to graduate school at Penn rather than Harvard. Whatever question was asked, he was never at a loss for an answer, however far-fetched.

His ability to correctly interpret what he saw was also out of whack. In the following days he valiantly tried out one scenario after another in an attempt to make sense of his incomprehensible surroundings: Sometimes the hospital was a library and the nurses librarians; he sent me off to the “stacks” to get the “tomes.” Seeing Tiger Woods on the overhead TV, he decided the hospital was a golf club. One afternoon, seeing a male nurse walk by wearing a yellow hospital gown, he said, “Look! Here come the gendarmes, wearing their uniforms with the gold braid.” Never before had I heard him speak with such verbal flourishes. Did they disclose sides of him he never chose to reveal to me, or did they signify something entirely new — perhaps mad?

All the nurses and residents assured me that Scott was merely suffering from “ICU psychosis,” a temporary condition that often afflicts people who spend weeks in intensive care. Everyone promised it would disappear as soon as he left the hospital, a hope I clung to until a speech therapist, after extensively testing him, finally told me that in her opinion, Scott’s short-term memory was completely shattered as a result of his multiple brain injuries. I asked her how long she thought this extreme memory failure would last. She studied my face, trying to assess my resilience before delivering her devastating verdict: “It could take years before we know the true extent of the damage.”

Doctors told me that Scott would need a year to heal. I accepted it without a moment’s hesitation. For one whole year my life would be aflame with purpose, single-minded and clear — to reclaim his life. There was no one else to do it, and nothing else remotely worth doing. I sprang into action, powered by hope and adrenaline. The problem was I got it wrong. What the various doctors actually said was that healing could continue for up to a year, for more than a year, possibly for the rest of his life, since every brain is different, and when the healing had run its course it would slow down and stop.

The worse things went for Scott, the greater my resolve to make them better. When new tests were scheduled, I insisted on accompanying him. When he lacked the energy to eat, I fed him. I counted every sign of his improvement a victory and every disappointment or frustration a temporary impediment.

Not that I was ignorant about his condition. Each night before sleep I fought despair by searching the Internet to see what was in store for us. I pushed myself to absorb the obscure intelligence on which our future depended. On a dozen websites all the symptoms and consequences of brain trauma were laid out systematically, scientifically: The disabling loss of memory, the general confusion, the attention deficit, the incapacity to follow instructions, the complete inability to plan or organize or even just know to put your pants on before your shoes (“sequencing problems”); the impulsive outbursts (“disinhibition”) that lead some sufferers to rage and curse at their caregivers or talk dirty to strangers; the bouts of agitation; the total blackout about the accident itself; and the evening delirium (“sundowning”) that produces delusions, fixations, hallucinations and paranoia in the cognitively impaired, particularly the elderly, in unfamiliar surroundings.

Eleven weeks after the accident, the social worker announced that Scott’s discharge date was set, with a strong recommendation of 24-hour care at home in New York. Could I, as certain well-intentioned friends suggested, turn him over to someone else’s care? (“You mustn’t let him take you down with him”; “One accident shouldn’t ruin two lives,” they said, trying to protect me.) No, I could not. During his first crucial year post-accident, my single task, unquestioned and unexamined, was to maximize his healing by supervising his recovery down to the minutest detail. I had no time, no interest, no energy for anything else.

The ideal of care I aspired to was the anti-nursing home. No drugs, no long naps. I would not allow him to doze his days away, even though left to himself he’d have done nothing else. For the eight remaining months of that first healing year, I devised stringent regimens to keep him alert and exercised. I took him to his therapies by subway instead of by taxi, forcing him to climb those challenging flights of stairs. I insisted, whenever possible, on walking to the library, the markets, the video store, the restaurants, stretching him to his limit, and once reached, I let him get a second wind in a park or a cafe before heading home. I reminded him to lead with the heel, not the toe, of his shuffling left foot, as his physical therapist prescribed.

At night we watched more movies than I’d have chosen to see in a lifetime. I’d have much preferred to read, but he refused to watch unless I joined him, on threat of going straight to sleep, which would risk his rising at dawn and rousing me with him. Instead I watched with him, then slipped out of bed to read after he was asleep, my only respite from his care. Compromise and accommodation, of which he was once a master, had now become my bywords. At the Museum of Modern Art, he insisted that part of the time I ride in the wheelchair, allowing him to push me. It was absurd! But because his inability to reason rendered my arguments useless, to humor him I gave in. Our luck, as soon as I was in the wheelchair, a woman from a seminar I attended stopped to chat with us, pretending that nothing was strange — for which I was grateful, since I was too embarrassed to explain.

Thus, reluctantly, did I become a tyrant. I told him when to ride and when to stand, when to sleep and when to wake, what to wear and what to eat. I instructed him on how far to walk, which way to turn, what door to enter, what key to use. On bad days, frustrated by the confusion that made him unable to comply with my wishes, he lost it and yelled — as much at himself as at me. Sometimes when I was impatient with his mistakes — when he put his pants on backward or reset the table as soon as we finished clearing off the dirty dishes — he was so disheartened by his failures that he vowed to shoot himself. When he stalked through the loft cursing, both of us felt battered and oppressed, though afterward he regretted losing control, as I regretted having to enforce it.

Everyone who cared about us said it was essential for me to return to the world and reclaim my life, as if it were something important I had temporarily parked in a checkroom.

But the sympathetic concern of friends only exacerbated my sense of alienation. “Are you taking care of yourself?” “Are you able to work?” asked one after another of those who worked, wrote, organized, taught and traveled abroad during sabbaticals and vacations. As the months slipped by, I felt the distance between me and the world expanding, like continents adrift.

My friend Sarah, a writer and retired psychology professor, visited from the West Coast. For the first time, I dared to leave Scott during daytime hours in order to have lunch with her, leaving him in the care of my most reliable Scott watcher. Sarah — whose husband, George, at 89 suffers from age-related memory impairment (ARMI) — is the only friend I had whose mate, too, was not always lucid. Comparing notes with her by phone always helped me think about my situation more clearly; it was a comfort to confess my secret thoughts and deeds to someone who knew firsthand what it was like.

As soon as the door closed behind us, Sarah shook her head and said, “If George were as bad off as Scott, I couldn’t take care of him the way you do.”

I didn’t believe her. “Of course you could if you had to. You’d have no choice.”

“No,” she said emphatically. “I wouldn’t give over my life the way you do.”

I hoped Sarah’s reaction wasn’t just another version of the response of certain friends who thought I should arrange for his care and get on with my life, as if his self had perished and he could be reduced to his disabilities — or of those who viewed me as incomprehensibly long-suffering.

For every friend who admired my devotion to my calling, another was indignant, perhaps terrified of finding herself in my place. “Are you trying to be some kind of hero or something, or is this just love?” asked one friend bluntly. “Your patience and forbearance are incredible,” e-mailed another, and of another I was told that she considered my caring for Scott “not a virtue but a vice.” As if I had a choice! Yes, it was often a drag to take care of him, I wanted to say, just as it’s often a drag to take care of your children, but you do it for love. Instead I replied to all of them: In my circumstances you’d do the same.

“What would you do,” I asked Sarah, “put him in a nursing home?”

“I’d hire someone else to care for him and live my life.”

I was shocked. Not only by her declaration, but by her view of my situation. It had plenty of problems and bad moments, yes, but it was also full of purpose and satisfactions, not least that of rising to the challenge.

Now, through Sarah’s eyes, I became aware that the life I was living was neither inevitable nor necessary: I actually had choices. And as we strolled through the stimulating streets on my first free walk since bringing Scott home, engaged in intimate, engrossing conversation that I had somehow forgotten could happen, I was stabbed by an awareness of all I’d lost. To walk with my head up and my eyes free, without having to guide Scott slowly through traffic or direct him to lead with his left heel not his toe; to walk without clock or duty tugging me back; to stride aimlessly with the bracing breeze riffling my hair and no purpose other than to exchange ideas with my friend and eventually find a pleasing restaurant felt like bliss.

Exactly as high as my spirit soared, it crashed to earth when I remembered how quickly my giddy sense of liberation was punctured by Sarah’s sobering words. Her stark view of my predicament shocked me into seeing the shape my life had assumed and the magnitude of my loss. All the passions, principles and hard-won habits I had built up over a lifetime had been undermined and overturned until, now, the writer whose work required solitude was never alone; the adventurer seeking experience was tied to one spot; the intellectual jouster could no longer exchange ideas; the book lover could hardly ever read; the political activist had abandoned the battlefield; the feminist devotee of equality who wrote “A Marriage Agreement” was a one-way caregiver to someone deeply dependent.

Such are the mysteries of the brain that even as my crisis deepened, Scott’s condition, after the one-year anniversary of his accident had come and gone, seemed to have stabilized. Physically, he was much improved. He slept soundly every night. He ate with gusto and appreciation whatever I served him, though choosing a menu was beyond him. His speech was fluent. With encouragement, he could now walk, albeit slowly, for three-quarters of a mile before fatigue cut him down. Emotionally, he was more responsive, frequently moved to tears by music and sad stories. He overflowed with spontaneous expressions of love and gratitude. The flip side of this “disinhibition,” a common TBI (traumatic brain injury) trait, is that he was also easily frustrated and quick to feel rebuffed, to which he responded, as he never did before his fall, by cursing, shouting, slamming doors, throwing things. With hardly any improvement in his severely damaged short-term memory, he still couldn’t recall having seen a film once it was over, much less follow a plot. Even if he couldn’t figure out how to work the door buzzer to admit visitors, his social skills were intact, enabling him to ask the right questions, seem to listen to the answers, and show concern for the comfort of our guests. He could fake a conversation so well that it took a long time for someone not in the know to realize anything was wrong.

Yet for all his continuities and improvements, if I asked him to do two things at once, for instance, take the napkins and the water to the table, he could manage only one. And every day he asked me shocking questions: When will we see your parents (who died 10 years ago)? What city are we in? Are we legally married? Can you please tell me how many children I have? Most disheartening, he couldn’t acknowledge that there was anything wrong with him. He still believed he was the same capable financier-turned-sculptor I married. Somewhere inside me, I knew that the moment might never arrive when we could resume our former lives. Instead of directing every effort toward his recovery, I turned to constructing for us as satisfying a life as possible, which would include time for him and for my own work as well.

One evening, after weeks of my caring for him without relief exhausted us both to the breaking point, during a minor spat he suddenly roared, grabbed both my arms, backed me against the wall and spit in my face, leaving me shaken by fear and rage. Breaking my own taboo, I said the unspeakable: I threatened to put him in a nursing home. In response he picked up a chair as if to hurl it at me, and I did the unthinkable — I called 911. “Now the police will come and take you away,” I said in my fury. As we waited for them, I wondered who was the abuser and who the abused, which of us was the more aggressive and which the more pathetic. The shock of what happened immediately calmed him, so that by the time four giant policemen strode through our door, we seemed like a courteous older couple living in quiet harmony. The minute they left, Scott forgot they had been there.

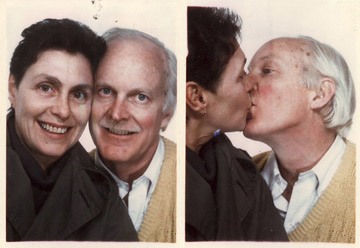

Two years on, sometimes I try to imagine other outcomes of that accident: If he had recovered enough to be reasonably independent. If he had been able to continue making art. If he had gone mad and had to be locked away. If I had sent him to a nursing home. If I had refused the respirator or “pulled the plug.” If he had died in his sleep. Then he would have been cremated, his ashes divided between his daughter and the ocean off Maine. And I would have launched another life. This thought alternately inspires and torments me. No more daily bondage, no more unrelenting responsibility. But at the same time, no ballast, no purpose, no love. Which would I be, light as the air or heavy as a gravestone? Giddily free or unbearably bereft? Forget it. He is alive, he is mine, and I am his.

“The right ending,” writes the novelist Michael Ondaatje, “is an open door you can’t see too far out of.” Whenever I try to imagine our story through Scott’s eyes, I draw a blank — or at best a projection of my own story. Even before his fall he was a private person whose inner thoughts I could seldom guess. How much less can I know now that his mind is usually inaccessible even to himself. If he attempts to enlighten me, he often gets it wrong.

Lacking understanding of what happened to him, he makes it up. What accident? he’ll ask when I remind him, and propose a trip to China. But I can’t claim to understand what truly happened, either. In his version, he’s just getting old; in my version, he’s gradually getting better. Neither is completely true, but we each cling to what we must believe, see what it suits us to see.