“Listen,” the men say, balded by time, or at least fattened up a little: “We’re still young, right?” And the women — many looking kind of broken-in, while the lucky few nod or shrug at the last limits of their prime — the women say: “Yeah, we’re like 12 years from middle age.” This claim will be right on the money if we live to be 100. (The bleak reality for 2008 Americans: Most of us die at just over 77 years.) It’s tough going, out here in the denialathon that is a 20th high school reunion.

For months, North Shore High School’s class of 1988 has been readying to suck in its gut and throw a party. My wife and I live in Brooklyn, N.Y., not too far from where my Long Island childhood happened. And so, I’m on my way — driving the expressway, watching the city’s grip ease on the land; already I’ve made it into Nassau County’s wide suburban ho-humness. Think of this as a quick summer-weekend drive straight into the uneasy past. High school was less than perfect for me. (If you’d stuck your compass point at the cool people’s lunch table, and made your radius the length of the cafeteria, you’d have usually found me fretting and mumbling at the far perimeter of your circle.)

Surprisingly, Manhattan casts a sort of undersized shadow onto Long Island. Where I grew up everyone seemed totally disconnected from the city — ours could have been any suburb, anywhere — though when traffic was thin it took us only half an hour to get into midtown. (The other reason I found high school difficult: Something terrible happened at the end of my time there, something I dread writing about even now, but that I’ll reluctantly share with you in a little while.)

And, 20 years after graduation, though they live so near the big town — they got nothing against the big town — many of my ex-classmates have stayed right where they grew up; and they never come into Manhattan except to commute to work and/or see a once-a-year Broadway show. It’s a choice many seem happy with.

That’s the second thing I notice, in fact — after the gray heads and the bellies — and it takes me by surprise: Everyone looks so happy.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

Our 10th reunion was kind of small potatoes, and so I haven’t seen most of these people since I wore 1988’s feathered Steve Perry mullet. Tonight’s event is going down at the special Swan Club, whose special Web site promises that “the moment you arrive on your special day you will indeed feel special.” The site tells us that the “dancing water fountains will enhance your photographic memories” — but we’re relegated to the mirrored, clinking Contessa Room, which “provides class.” I’m pretty sure there’s a concrete angel standing next to the entrance.

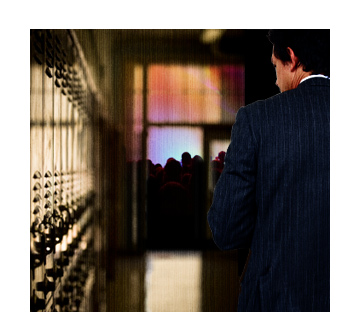

For all that, the light falls harshly here. And it feels like I’m straightening my posture for a grade school photo, mustering up my Platonic internal image, trying to project that model self against the real world’s view of me. Then I notice: Everyone’s playing the self adman, the PR maven. Everyone’s trying to hide the debt they’ve started paying down to time.

“Hey, you look … great?”

“Yeah, thanks, thanks. Is this your wife?”

That’s how it goes. Watch people’s nostrils stiffen up as they scrutinize you. It’s like when you get that class photo back: You clearly didn’t put one over on the camera, after all. It isn’t your model self; it’s the real you, the wanting you, that’s uncovered.

Here’s the first tough question of the reunion: Is it real, everyone’s apparent joy in seeing each other? Hard to tell. The night resists the taking of its pulse; there’s just no way to get an accurate reading. I feel happy to be here, I’m pretty sure. But we all have so much to talk about that we all have nothing to talk about. We go out all at once into torrents of cliché, gusts of the same old stuff. “Enjoy those kids now; they grow up so fast” — I hear this six times, from five different people. “I can’t believe it. Twenty years!” I say that nine times. This isn’t conversation; it’s word fog.

And everyone stares. We’re in a peep show — a peep show offered in a nostalgia wrapper. Which is no kind of peep show at all: We reveal something of ourselves (married or single; white- or blue-collar; kids or carefree). But, our eyelashes fluttering, we hold kerchiefs and veils over the interesting parts.

Here it’s probably necessary to disclose the awful thing that happened. When I was 18, a younger student from North Shore pedaled her bicycle directly into my moving car. She died. It was harder than you can imagine and life-changing, and I can only write about it now because 20 years have passed. To discuss it face-to-face remains a crackling horror. And yet here I am.

I had the accident just weeks before graduation. As soon as school finished, I left town immediately; I didn’t even stay for summer break. Maybe coming back tonight is a way to convincing myself that I really am over it. Or to see whether people view me as the boy who’d spent 13 years in class with them before the accident, or just someone who’d taken part in a fatal event two weeks before the end of school.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

Walking by the Swan Club’s quiescent dance floor, I hear some unseen person address me: “D-fucking-Strauss!” — in a friends-from-way-back tone. (I never thought I’d been that guy, referred to as First-Initial-slash-F-Bomb-slash-Last-Name. Had I been that guy, referred to as First-Initial-slash-F-Bomb-slash-Last-Name?)

I don’t recognize the speaker. But then I do. And I can’t believe it. But the speaker, a skinny Dionysus back when, looks almost exactly as he had — except some bastard appears to have popped a bike pump in his ass and inflated him to the breaking point.

We ask each other how we’re doing; we answer at length, then we smile. Then that’s done with. (I find I’m afraid of writing critical stuff about people from my high school.) This dude and I keep nodding for a time. Drops of light twinkle in his glass. The cracks in old friendships are measured in awkward pauses. “Yeah,” we both say, apropos of nothing. The dude’s moist pink face looks overfull, almost contused, like that of a club fighter. (I mean — why I’m afraid to be critical is that I want, just as I did back then, to be liked. That’s not about the accident, I don’t think. Nobody’s mentioned the accident yet, and, what’s more surprising: I haven’t been thinking about it that much. I’m more focused on/freaked out by how people look.)

Things aren’t often like this. None of us hangs with 16-year-olds regularly, so why does talking to people crowding 40 seem so odd tonight? That’s a tough one. Normally, aging is an inappreciably plodding deal. Tonight it’s a special effect, a frame advance, a CGI morph into transformation and decay.

And yet.

A woman I’d always admired but never really knew comes over, gives me a cheek kiss — “Darin!” — and tells me how nice it is to see me; now I’m sure I’m glad I came. Of course, what I enjoy here is the undiluted ego gratification.

And that’s the point, obviously. This is remembrance (moonbeams and smiley kittens version). Etiquette decrees that we must pretend everyone had a comparable high school experience. That means that we have to sugarcoat the past via our present behavior. And here’s how we sugarcoat the past: The popular girl and the nerd with pimples share a hug. The cheerleader then walks away convinced she was more open-minded in school than she actually was. The mathlete can sleep better in the faith that, hey, people liked him after all. But it doesn’t feel sane. The dissonance is this: Here we have a totally sentimental rite set against the perfectly seeable truth — that fact and need, myth and the mirror, have no correlation.

Maybe that’s why I haven’t thought of the accident that much; maybe I’m here to rewrite my high school life — to give it the dramaless ending, the normal and event-free changeover to college; to make my remembrance the same as yours.

Not that I don’t have a good time for much of the night. Of course I do. I laugh with old pals (all of whose names I changed here, by the way). And I get to reunite with Sarah Canilio, my one-time girlfriend, or sort-of girlfriend, or at least two-time prom date. (Adolescent romances were often perplexing, especially when the adolescent involved was perplexing, perplexed me). Sarah, now a tan stunner at 6 feet, is engaged to be married for a second time; she sells real estate in Florida and says she models a little. We never, even back in the day, talked that much. But I always felt Sarah Canilio and I shared an under-the-surface consociation, a winking like-mindedness about people. Now, as I smile and fret my posture, this very pretty late 30s woman and I gape at each other — but no silent conversation passes back and forth between our eyes, not anymore. The communication lines have been cut. I stand facing her with helium shoulders and nothing to say.

So, the event feels weird. It’s not only that the laughs and the disappointments alternate in quick succession. It’s that the evening is draped in a naive pointlessness; yes, totally glad we’re great friends again, see you in 2028.

As the night shuts down, I talk with Danielle Winthrop, an easy smiler, very feminine with a no-nonsense wide forehead and big, almost black eyes — someone I’d once found almost too regal in her prettiness even to sit near. Time, I figured, would have bought me the requisite emotional lifts; a standing-taller-in-the-shoes feeling, a newly expansive view of life’s playing field. I’m a very happily married guy who knows he’s lucky with his family of supercute, 9-month-old twin sons. But, for some reason, I now feel wordless before Danielle Winthrop in just the way I did in high school, totally dumbstruck. This has nothing to do with present realities. This has nothing to do with the accident. This is unpopularity worked into the genes. To shake the feeling, I watch the old groupings — the jocks and the studyers, the stoners and the try-hards — as they all revert into their old 12th-grade dance steps. It all goes down with a familiar tang. Late-night keg parties, too-loud music, everyone yelling, cigarette smoke and timidity. Standing here tonight, unable to act like my adult self, I feel the contours of a hundred remembered nights fall over this one.

On such milestones as this, our hold on the present loosens. We believe, for an evening, that we’ve been fooling ourselves these last 20 years, and that this is what has really remained central to our lives — the anxiety, the immaturity, all the old phantoms — while the victories, the self-work and changes that have marked our entire adulthood are gone. It’s as if the footnotes have become the main text of who we are.

Finally, talking with Danielle Winthrop, I learn the last lesson of the night: Memories that had set and hardened can still crack.

I’d always remembered Danielle as one of the grade’s “popular” girls, deluged under a would-be boyfriend Niagra. In fact, Danielle never dated anyone in high school. She blames that on an endemic racism. (Danielle is half-black.) And somehow this all — the probable racism, her dateless past, the fallibility of memory, tonight itself — seems terribly moving. Truths of my life surprise her, as well. She’d never realized, for example, that I’d been a bashful kid who felt miles from the action. “And I don’t associate you with that accident, to answer your question,” she says. “People know it wasn’t your fault.”

This is what I wanted to hear; I don’t know why it upsets me. And then I do know. Someone died. Why aren’t people — why am I not — thinking more about it? I feel bewildered. The bewilderment keeps up even as I look again at other conversations. People check the mirror as they talk — some men palm at the cloud cover of their thinning hair; some women lift their heads to mitigate their double chins — people clueless about how young they’re failing to look, clueless about the truths that only come to us softened by the beautiful stratagems of self-deception and wish.

Then my reunion is over. My ex-classmates and I move to the doors together in a kind of funnelform procession, just how we left the school at the end of the day. Outside, we walk past the angel statue that abuts the valet parking area, its sand-colored arms bent to pour water incessantly into some concrete tub at its feet. Keys tinkle as they’re handed to my ex-classmates; there are a lot of nonchalant goodbyes at my back. A woman’s lips touch my cheek. Headlights admire Sarah Canilio’s face for a moment before the car turns away. Maybe I’ll see these people again, maybe not. Maybe some friendships have been relighted here, but I doubt it. What’s been said among this group who were the stars of each other’s lives has been said already, or won’t ever be said. People wave goodbye and show, for some reason, the strangest little smiles, without looking each other in the face; the sand-colored angel smiles inexplicably too, as it keeps pouring water.