Internal documents and e-mails show that Navy officials unfavorably doctored a psychiatrist’s performance record after he blew the whistle on what he said was dangerously inept management of care for Marines suffering combat stress at Camp Lejeune, N.C. The internal correspondence, obtained by Salon, also includes an order to delete earlier records praising the work of the psychiatrist, Dr. Kernan Manion, who was fired last September after lodging his complaints.

Now top Navy officials are tangled up in the blackball campaign. Soon after Manion was fired, Rep. Walter Jones, R-N.C., asked the Pentagon about Manion’s concerns about healthcare at Camp Lejeune. In a Dec. 17 letter to Jones, Navy Secretary Ray Mabus panned Manion’s ethics and professionalism, presumably based on information Mabus received about Manion from Camp Lejeune.

But Salon has obtained internal Navy documents and correspondence that suggest officials at Camp Lejeune altered Manion’s favorable personnel records after he went public with his concerns, adding new, derogatory remarks similar to some of the information in Mabus’ letter to Jones.

As Salon reported in November, Manion warned superiors, on multiple occasions and in writing, that mental healthcare at Camp Lejeune was overwhelmed with Marines suffering psychological injuries from combat. It was a toxic environment, Manion argued, that would only contribute to a rapidly escalating suicide epidemic in the military.

Manion also warned the situation at Camp Lejeune threatened to provoke a Fort Hood-style explosion of violence, or one like the acts allegedly carried out by Sgt. John Russell, who the Army says last May executed five fellow soldiers at a military mental health facility in Baghdad. Manion also claimed that troubled Marines sometimes experienced harassment from superiors for seeking help.

In one instance last April, for example, Manion warned Cmdr. Robert O'Byrne, head of mental health at the Camp Lejeune Naval Hospital, of "immediate concerns of physical safety" due to mistreated Marines teetering on the edge of violence. “There was -- and continues to be -- no means of discussion of high-intensity/dangerous cases,” he wrote. Later that month, Manion quoted to O’Byrne some Marine superiors who were calling troubled Marines “worthless pieces of shit” if they sought help.

Frustrated by what he said was little reaction from O’Byrne and other superiors, on Aug. 30 Manion notified a series of military inspectors general about the risk of “immediate threat of loss of life and/or harm to service members’ selves or others.”

Manion worked as a contractor for Spectrum Healthcare Resources, a subcontractor for NiteLines Kuhana. The contractor told Salon that the Navy ordered Manion fired on Sept. 3, four days after Manion wrote the inspectors general. "The treatment facility at Camp Lejeune notified [NiteLines] that Dr. Manion did not meet the Government's requirements in accordance with the contract, and they directed he be removed from the schedule," it reads. His termination dated that day notice provides no explanation.

Manion saw a case of retaliation. He has hired a lawyer. Manion also appealed to his congressional representative, Jones. That is when Jones asked for an explanation from the Pentagon last year.

Jones’ inquiry prompted the Dec. 17 response from Navy Secretary Mabus. That letter includes some stinging allegations about Manion. “Dr. Manion alleged he was improperly terminated from his job due to the complaints he raised concerning patient care,” Mabus wrote Jones. Not true, Mabus said. “A review of the record revealed that Dr. Manion was removed from the contract due to a sustained pattern of non-compliance with numerous contract stipulations,” he wrote, including absenteeism, disrespect and unprofessional conduct. Mabus added that Manion had been “counseled on multiple occasions but with little effect.”

While Manion’s activism likely chafed some Navy officers, he was never counseled for poor performance, he insists. “Nobody counseled me, ever,” he said. Referring to Mabus’ letter, Manion added, “That was the first I had heard of it.”

Jones told Salon he worried that Manion might have been slandered. “We continue to monitor this issue because we are concerned that Dr. Manion has not been treated like a professional,” said Jones. “We intend to get to the bottom of this because integrity does matter.”

The paper trail suggests Jones is right.

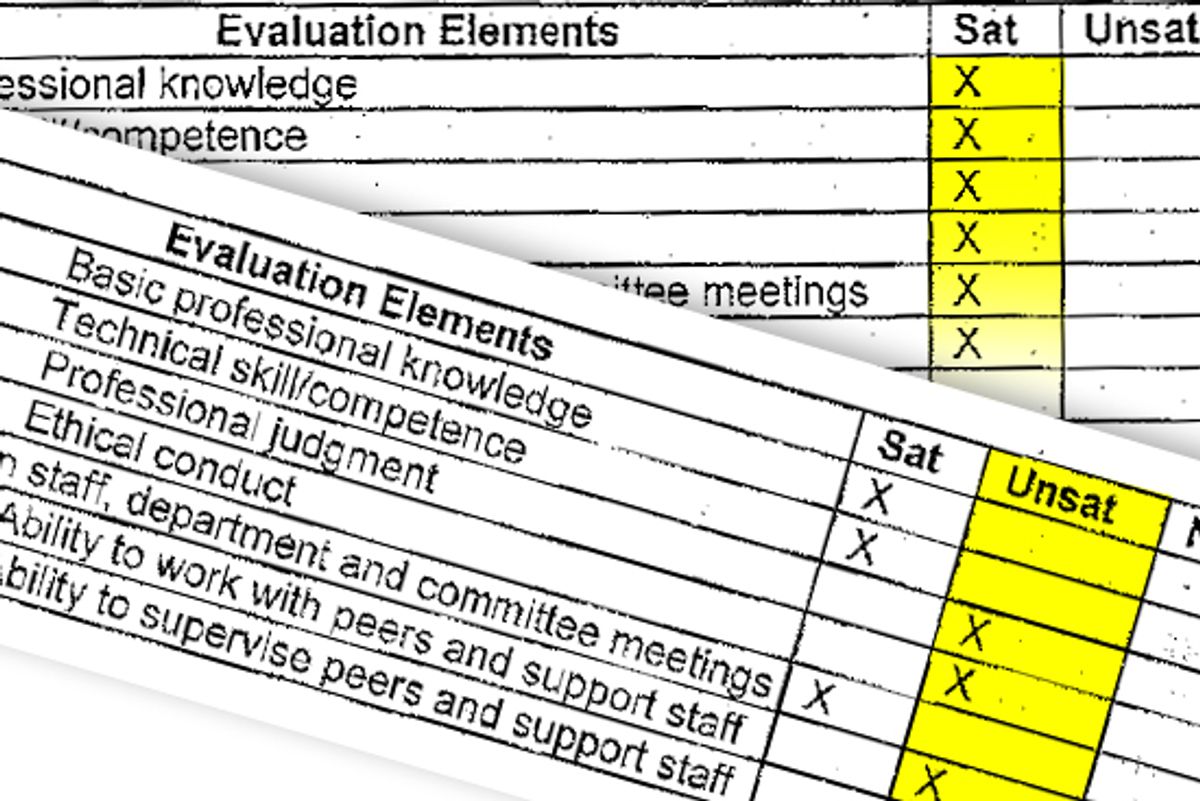

Manion was fired on Sept. 3. A lieutenant commander filled out Manion’s final performance review, called an “exit PAR,” and signed it on Nov. 10, 2009. The document, obtained by Salon, evaluates Manion as “satisfactory” in every applicable performance category, including his judgment, ethical conduct and ability to work with peers.

On Nov. 14, Salon published the first article chronicling Manion’s concerns about the management of mental health care at Camp Lejeune. The article included his allegation that he was fired for blowing the whistle.

On Nov. 24, O’Byrne, the head of mental health, e-mailed that lieutenant commander about the exit evaluation. “I pulled it back,” O’Byrne wrote. “We need to redo.”

O’Byrne sent the evaluation back to the lieutenant commander on Nov. 30. “Please see section VIII and XII of the attached specifically for comments I think capture the essence of what we discussed last week,” O’Byrne wrote.

In section VIII of this new evaluation, Manion’s professional judgment, ethical conduct and ability to work with peers had been changed from “satisfactory” to “unsatisfactory.” A new paragraph, labeled XII, now included, “Dr. Manion demonstrated poor ethical conduct and professional judgment.” It added that Manion had “disruptive relationships with his superiors and peers that had a negative impact on patient care and clinic process.”

In a Dec. 3 email, O’Byrne orders the previous, flattering version of Manion’s review destroyed. “Due to the sensitive nature of issue [sic]” O’Byrne wrote, “please immediately delete all copies of this PAR.”

The lieutenant commander who filled out the original evaluation seems to have stuck to his guns, insisting that Manion performed his job well. He wrote a Camp Lejeune attorney on Dec. 16 that despite O’Byrne’s changes to Manion’s records, “Kernan Manion was considered clinically competent to practice general psychiatry,” he wrote. “I had no specific concerns about his judgment or ethical conduct.”

In that exchange, the lieutenant commander described O’Byrne’s changes to Manion’s evaluation as “drastic.” He added that he was “instructed to sign” the new evaluation.

O’Byrne declined an interview request from Salon. “The allegations in question are completely unfounded and untrue,” Camp Lejeune hospital spokesman Lt. j.g. Mark Jean-Pierre said in a statement to Salon. (Despite numerous requests, Jean-Pierre would not say which allegations are unfounded and untrue.) He went on to suggest that Manion, or perhaps Salon, was irresponsible. “The fact that such accusations are being made against a senior naval officer with an impeccable service record is not only wrong, but irresponsible,” the statement says. It adds, “Officers are held to the highest standards and any behaviors that contradict the naval core values are not tolerated.”

Salon asked the Navy two questions: 1) What is the basis for the derogatory information about Manion in Mabus’ letter? And, 2) What is Mabus’ basis for believing that information is accurate?

The Navy did not answer either question. Instead, a Navy spokesman sent Salon a statement saying the Navy had already investigated Manion’s original concerns about healthcare at Camp Lejeune. “The allegations made by Dr. Manion concerning mental health services being provided at Camp Lejeune were thoroughly reviewed in a recently completed quality assurance investigation,” Navy spokesman Lt. Justin Cole said in a statement to Salon. Cole also added that Navy would not share the results of that investigation. “The results of the quality assurance investigation, to include its findings and recommendations, are not releasable.” Cole insisted, however, that Navy officials were taking unspecified “action” in response to the results of that investigation.

The contractor that hired and fired Manion did not respond to a request for comment on the changes to Manion's Navy personnel records.

Manion insists he never heard a word about his allegedly poor performance until he reviewed the documents obtained by Salon through multiple sources. Indeed, after his termination by the contractor back in September, Manion wrote the Navy Medical Logistics Command arguing that his otherwise-clean record provided further evidence that he was fired in retribution for blowing the whistle. “Given that I have received no allegations of wrongdoing by any party throughout the course of my employment and given that this termination occurred in the immediate context of my having filed an emergency complaint with the inspector general’s office,” Manion wrote Sept. 30, “I am concerned that your office may not have been aware of such an action having been taken.”

Now that this new paper trail has emerged, Manion has responded by firing off a series of letters to Camp Lejeune officials, including O’Byrne and Manion’s former contractor employer, requesting access to his own personnel files. “I think it is both fair and important that I have the immediate opportunity to review my full personnel assessment, particularly that which pertains to…blatantly false characterizations, so that I may respond in detail to it.” Manion says he recently received a response from the hospital commander at Camp Lejeune, Capt. Gerard Cox, saying Camp Lejeune would process his request through the Freedom of Information Act.

Eugene Fidell, a professor at Yale and president of the National Institute of Military Justice, said it is unclear whether tinkering with Manion’s performance record could result in judicial punishment. It is possible it might violate any number of complex military regulations governing performance evaluations.

Wasting time smearing Manion, however, also seems like a misplaced priority for Navy mental health officials battling an unprecedented military suicide epidemic during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2008, for example, 42 Marines committed suicide and 146 tried to do so. During the recent Pentagon's second annual Suicide Prevention Conference, the military announced that 52 Marines committed suicide in 2009, surpassing the national average.

Manion agreed. “That’s precisely what I was trying to address,” Manion said. “It is a crisis of suicides.”

Shares