In the mid-19th century, a German taxidermist named Hermann Ploucquet created an exhibit of anthropomorphized beasts for London’s Great Exhibition. He stuffed a group of squirrels and posed them smoking cigars around a poker table. He dressed up frogs like longshoremen, barbers, drum majors and King Lear. The exhibit caused a sensation and launched a golden age of taxidermy, the finest achievement of which may be Walter Potter’s 1890 diorama “Kitten’s Wedding”: 20 kittens in black suits and brocade dresses, tearfully observing a nuptial couple.

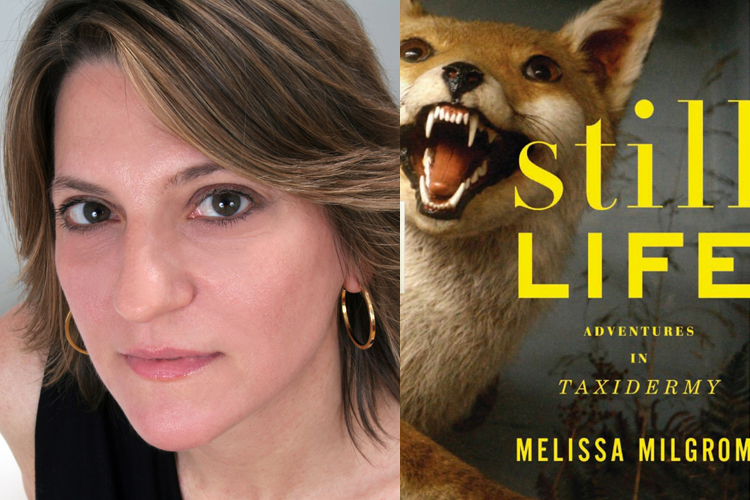

Even in the age of Lolcats and Sugar Bush Squirrel, taxidermy, the subject of Melissa Milgrom’s riveting new book, “Still Life: Adventures in Taxidermy,” remains an esoteric and divisive field. But Milgrom proves there’s little reason for the latter. Most taxidermists, after all, are animal lovers, humbly striving to glorify the majestic animal form. As part of her research into how taxidermy is practiced today, Milgrom attends the World Taxidermy Championship, and even enters her own stuffed squirrel into a novice competition at the Smithsonian.

Salon reached Melissa Milgrom by phone to talk about the woman behind Damien Hirst’s famous shark, the controversy over museum dioramas, and what it’s like to stuff a squirrel.

What gave you the idea that you should write a book about taxidermy?

I grew up in suburban New Jersey, so I was pretty far removed from wildlife of any kind. Then I found out that David Schwendeman, who was the last chief taxidermist for the American Museum of Natural History, lived a mile from where I grew up. Everybody knew about his shop. So one day I wandered in, expecting everybody to be elbow deep in macerating carcasses, since that’s what movies like “Psycho” and pop culture in general taught me to expect.

But it was such a special place. It was like falling into Victorian-era England, with all these skeletons, butterflies, birds and strange tools. I knew right away there was a book here, because of the contradiction. Here was this gentle birder who’d been branded an animal killer. At the time, though, nobody would consider taxidermy as a book idea, or even an article idea. It was just too creepy and obscure. But times have changed. Taxidermy is en vogue now.

Taxidermy is en vogue?

Yes, in a way. I think that as a culture we’re all responding to the mass extinction being brought on by climate change, even if we don’t know it. The Victorians, in a similar if opposite way, were collecting in excess because they were so excited by these new specimens being brought over from Africa and South America. The current popularity may have something to do with impending scarcity and preserving the exotic. Anyway, what’s Build-a-Bear Workshop but taxidermy for kids? Or the Rainforest Cafe, or “Fantastic Mr. Fox”? The Victorians were interested in the same kind of anthropomorphic tableau. It may just come down to an amateur, non-scientific love for animals.

Do you consider taxidermy an art form?

The taxidermists that I respect the most call taxidermy a highly skilled craft. Some taxidermists will actually remove every whisker and reinsert them individually to create the right mood. But it really is an art, I think. It has to be perfect. If there’s any distortion, it’s immediately recognizable. You don’t need to know much about a squirrel to know that it’s off. When they do it right, it’s like good writing — you just glide over it. So in that sense, taxidermists don’t get any credit as artists, because they’re restricted to an absolute imitation of nature.

There are no abstract taxidermists, then?

Not that I’m aware of. And yet Emily Mayer, Damien Hirst’s taxidermist, has done this cow that’s split down the center, spilling its guts. Its power comes from how unbelievably realistic it is. Although she works in the arts, Emily is still a respected taxidermist. She’s been doing it since she was 12. She pushed taxidermy to the nth degree, until she got bored with it and went to art school. She felt she couldn’t express herself through taxidermy. She sometimes calls herself an anti-taxidermist.

Emily’s a sculptor in her own right, but she does a lot for Damien. She articulates skeletons for him, makes little blood puddles with flies. The famous shark in formaldehyde is a real cadaver, but she repairs it, and keeps it looking real. When I visit her in England, I have to poke her taxidermy dog to see if it’s alive, because she poses it with its eyes closed, like it’s asleep. The dog’s snout looks wet. The Times review of the “Still Life” called her a Tim Burtonesque perfectionist, and I thought that was accurate.

Most of us associate taxidermy with museum dioramas, but, as you write in the book, museums weren’t always keen on the idea.

After Darwin, museums became consumed with taxonomy. They didn’t want any artistic taxidermy — things like dioramas, or a portrayal of a tiger about to maul someone. In England, there were actually wars between the people who prepared specimens for the museum. Certain people, like the naturalist Charles Waterton, couldn’t stand the [laboratory-style] taxidermy that was practiced in museums; they felt it took the life out of these creatures that they loved, who were best represented in action. Taxidermists in the U.S. began holding competitions to show that it could be an art form. And eventually, museums decided that dioramas could educate the public about conservation.

What are taxidermists like? Are they obsessed with death?

This took a long time to understand, but the common thread seemed to be a love of animals, and the resulting desire to get their models right. Taxidermists see beauty in dead animals. If they see a dead bird on the ground, they’ll have feelings for it. I’d include Damien Hirst in this category. I’m not an art critic, but I look at Damien’s work through the eyes of British natural history, which he’s fascinated by. He tried to buy Mr. Potter’s Museum of Curiosities, this giant collection of anthropomorphic dioramas, for a million pounds, partly so that the collection would remain together, and not be dispersed.

Has taxidermy ever been applied to humans?

Well, there’s the famous case of Jeremy Bentham, a British economist and philosopher, who donated his body to University College London, where he can be seen today. He added a clause in his will requesting that his real head, which is usually replaced by a wax head, be brought out during dinner parties. And then there’s El Negro. French taxidermists had stuffed an actual African man and put him in a museum in Spain, until he was finally repatriated to Botswana and buried in 2002.

Aren’t the human body exhibitions, like Body Worlds, taxidermy?

No, those are just specimens preserved through plastination. Weirdly, I have no desire to go to it. Maybe it’s just too close. By contrast, taxidermy, at its best, allows you to interact with it; it’s emotional and transporting. There’s a nice quote from Baudelaire, in which he compares what he calls the “brutal and enormous magic of dioramas” to theater. He says, “These things, because they are false, are infinitely closer to the truth.” I love that line.

In the book, you describe your attempt to stuff a squirrel. What was the biggest challenge?

I couldn’t pull the bone out of the tail, for one. But the whole thing was really hard. It’s very intricate, and the fact that they’re skinny is kind of gross. I accidentally put the thigh bone in place of the arm, and had to redo it. A real taxidermist would know the anatomy of that squirrel; they would have studied it in the wild, out of a desire to understand nature on its own terms. I didn’t do any of that.

How has seven years of researching taxidermy changed your outlook on the profession?

Nothing grosses me out anymore. [Laughter] But mainly, it’s given me an extreme respect for taxidermists. They are portrayed very poorly in the media, but those I wrote about were really fun to hang out with. As tradespeople they’re very real and unpretentious. It’s an insular world, and very tightly knit, just as any group with a lot of prejudice against it will be. The scientific bird guy and the backwoods deer-head guy have a certain camaraderie.