The New York Times’ Floyd Norris is surprised that “many commentators, whether economists or politicians,” are in denial that the U.S. recession is over and that the economy is poised for a sharp upswing. Color me perplexed at his confusion.

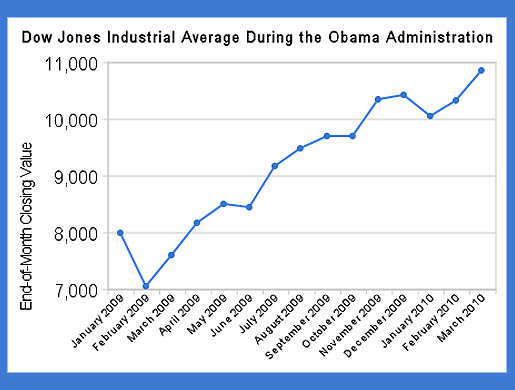

I will concede that there’s little doubt that the past three months have witnessed the rosiest economic indicators since before the Great Recession began. The stock market is plugging away merrily, payrolls are finally growing again, consumer spending is rising, and companies are reporting stronger-than-expected earnings. We can cheer ourselves up with a slew of encouraging charts. Compared to where we were a year ago, we’re in great shape.

So why, as Norris asks, “is good news being received with such doubt?” Norris suggests that it’s been so long — dating back to the early ’80s — since Americans have experienced a robust rebound from a savage downturn that we no longer even believe it’s possible. So we dismiss stock market growth and corporate earnings while expecting yet another jobless recovery and wage stagnation.

But I think there’s more to our pessimism than lack of imagination. You don’t have to look hard to find plenty of reasons for caution.

Let’s start with housing. Normally, a rebound in the residential housing market drives economic growth early in the recovery from a recession. That’s not happening right now. The free fall in home prices has abated, but that could be just temporary: there are clear signs that another big wave of foreclosures is about to crash. As noted in the Federal Open Markets Committee minutes released earlier this week, “housing sales and starts [have] flattened out at depressed levels, suggesting that previous improvements in those indicators may have largely reflected transitory effects from the first-time homebuyer tax credit rather than a fundamental strengthening of housing activity.”

Next up: unemployment. Norris reminds us that unemployment is a lagging indicator, and tells us that labor markets are already bouncing back faster than they did after either of the last two recessions, but that’s scant relief to the 3.4 million people who have been unemployed for longer than a year (23 percent of the total unemployed, the highest percentage registered since records started getting kept after World War II). There are six people for every job opening right now — and that’s a ratio that does not nurture optimism. The number of people filing for new jobless claims has remained stubbornly high, as proven by this week’s 18,000 jump upward.

Lurking in the wings: Another energy shock. The price of a barrel of crude is hovering near its highest point since the height of the financial crisis, around $85, months before the traditional summer driving season in the U.S. gets under way. Ironically, the resumption of global economic growth will inevitably push oil prices higher, placing further strains on fragile household finances.

And let’s not forget the looming end of government assistance. We can debate just how much of current economic growth is accounted for by stimulus spending, but only the most partisan commentators will attempt to claim that there has been no impact. So what happens when the spigot gets turned off?

So here’s a scenario: The housing market slump deepens, with prices forced down by a wave of foreclosures and short sales. Oil prices spike. Stimulus spending peters out. The hundreds of thousands of temporary workers hired by the U.S. Census are released back into the labor market. Politicians, paralyzed by deficit fears, are unable to take further stimulative action. Throw in the wild cards of a China bubble popping or a Eurozone debt crisis, and you have plenty of reasons to be wary of the future.

I hope I’m wrong, and in fact, I’m constantly looking for excuses to be cheerful. But at the same time, I am most certainly not surprised that anyone else might feel a surfeit of caution about our economic future.