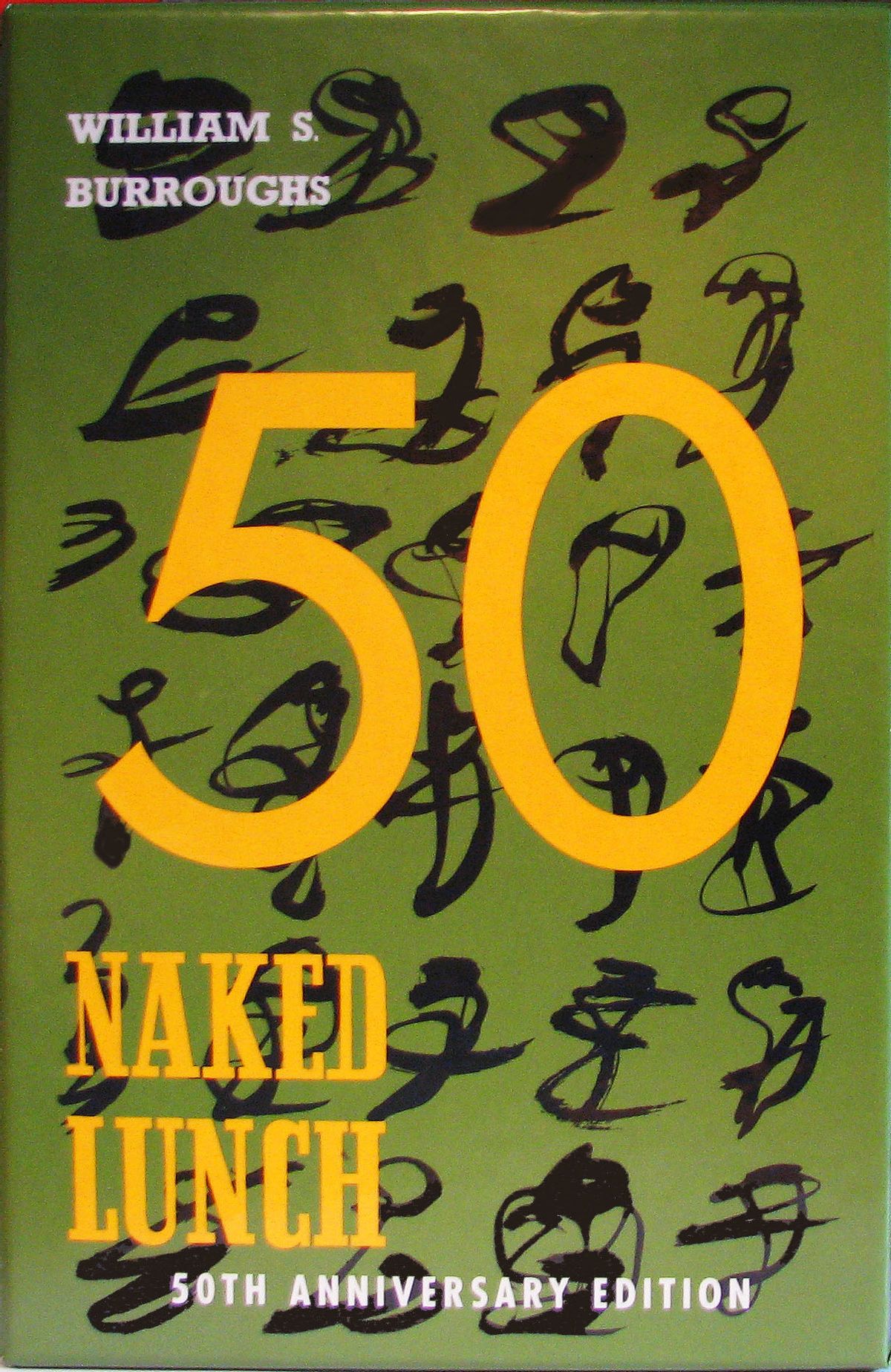

Everybody remembers his first time. Nobody talks about William S. Burroughs's "Naked Lunch," which celebrated its 50th birthday this past November (dated from its 1959 publication in Paris by Maurice Girodias' infamous Olympia Press), without indulging in a dreamily solipsistic nostalgia trip. Lewis Jones, in the London Spectator: "When I first read "Naked Lunch," as a teenager sleeping rough in a Greek olive grove ..."; Barry Miles, the author of a hilariously credulous Burroughs biography ("El Hombre Invisible") and co-editor of this commemorative volume, on a Columbia University panel: "I was living in this hippie commune apartment in London ... The book completely knocked me out, the epitome of stoned humor and bohemian subversion."

I'll join in the fun. I first encountered "Naked Lunch" in eighth grade, in the backseat of my parents' car -- a clear-cut case of child abuse by neglect. I'd purchased it on a family outing to Waldenbooks, a store that, it's interesting to note, mostly traffics in kitten calendars and "Cathy" bookmarks. "Please," I thought, "don't let Mom ask to see this." You could read any page at random -- as Burroughs essentially intended, once insisting in a letter, underscored, and in all caps, that it wasn't a novel -- and get sick to your stomach. "Junk sick," as Burroughs would say, in another context.

Why is "Where were you when ...," a question for assassinations and catastrophes, so often asked with respect to this book? Maybe because reading "Naked Lunch" is an act of violence to one's psyche. Jack Kerouac, who suggested the book's title (based on a misreading of the phrase "naked lust") and typed up the manuscript, claimed it gave him nightmares. Good for him, or at least for his unconscious mind. There is something gratingly adolescent about those who insist on the essential humor of a work replete with violent interspecies pornography ("The Mugwump pushes a slender blond youth to a couch and strips him expertly"); fetishistic descriptions of putrefaction and disease ("[h]e's got a prolapsed asshole and when he wants to get screwed he'll pass you his ass on three feet of in-tes-tine"); and general nastiness ("Did I ever tell you about the man who taught his asshole to talk?").

Why is "Where were you when ...," a question for assassinations and catastrophes, so often asked with respect to this book? Maybe because reading "Naked Lunch" is an act of violence to one's psyche. Jack Kerouac, who suggested the book's title (based on a misreading of the phrase "naked lust") and typed up the manuscript, claimed it gave him nightmares. Good for him, or at least for his unconscious mind. There is something gratingly adolescent about those who insist on the essential humor of a work replete with violent interspecies pornography ("The Mugwump pushes a slender blond youth to a couch and strips him expertly"); fetishistic descriptions of putrefaction and disease ("[h]e's got a prolapsed asshole and when he wants to get screwed he'll pass you his ass on three feet of in-tes-tine"); and general nastiness ("Did I ever tell you about the man who taught his asshole to talk?").

The book is very occasionally funny, in a Mickey Spillane meets the Marquis de Sade kind of way, but its savage imagery, non-linearity, repetition and plotlessness make it something worse than nightmarish -- they make it boring, even embarrassing. There are frequent authorial intrusions along the lines of "Note: Catnip smells like marijuana when it burns. Frequently passed on the incautious or uninstructed." The reader begins to feel like a baby sitter whose young charge is describing an R-rated movie he was accidentally allowed to see. In Burroughs' case, the movie is about opiate addiction, which he deliberately cultivated over a lifetime, perhaps for something to write about.

Burroughs the man was as awful as he was beloved. He enjoyed a very comfortable upbringing in St. Louis -- his grandfather invented the adding machine -- and received an allowance for much of his life, but petulantly insisted "we were not rich." He had a son he didn't take care of, whose mother, Joan Vollmer, he'd shot dead in a drunken game of "William Tell." Adding insult to murder, he spent much of his writing life glorifying the incident, imagining that a so-called Ugly Spirit had invaded him and forced his hand. He even attempted a kitschy sweat lodge "exorcism" late in life, described in nauseatingly approving detail in the Miles biography.

Burroughs is often said to have exerted a major influence on popular culture. This seems limited to the fact that his work is alluded to in a Joy Division song ("Interzone," named for a setting in "Naked Lunch"); that he has a brief role in Gus Van Sant's "Drugstore Cowboy" (1989); that he has an even briefer cameo in a U2 video; and that the rock group Steely Dan is named after a dildo featured in "Naked Lunch."

It is unthinkable that Burroughs' writing had a significant influence on anyone above high-school age. "Naked Lunch" is ostensibly about addiction and "control"; Burroughs and his myrmidons have even argued that the pornographic leitmotif of hanging represents a Swiftian satire of capital punishment -- nice try. Really, it is about shock for shock's sake, as is apparent to the precocious young people to whom it tends to appeal, and as is doubly apparent in the fact that it is remembered by readers as a sensation rather than in terms of its contents. Nobody will quote "Naked Lunch," not even its scabrous Dr. Benway, as literature -- if at all, it will be as an inside joke.

"Naked Lunch" is one of those regrettable works that must be defended on the grounds that it does well what it set out to do, with no consideration given to whether what it set out to do is worth doing. It is very like a nightmare -- so? Its vocabulary is pathetically limited, with "insect," "erectile," and "atrophied" appearing as adjectives over and over again, whether or not they make any sense; its stunted imagination reaches reflexively to drug culture and medical or anthropological gross-out lore. Its satire is all telegraphic, all punch line: Just because you have a loudmouth Southern sheriff or a big-city detective, doesn't mean you've said anything useful or interesting about racism or due-process violations.

Burroughs is one of those figures whose intelligence is overestimated because, slight though it is, it contrasts sharply with his outrageous public persona. Even on the subject of narcotics, the one thing he should be expected to understand, he's hopelessly muddled. His "Letter From a Master Addict to Dangerous Drugs," printed in the British Journal of Addiction, Vol. 53, No. 2, and appended to this and to other editions of "Naked Lunch," seems oblivious to the fact that a sample pool of one person is not medically valuable. And he writes in "Deposition: Testimony Concerning a Sickness" that "[t]he junk virus is public health problem number one of the world today" (emphasis his), only to pretend three decades later, in "Afterthoughts on a Deposition," that he was referring to "anti-drug hysteria ... a deadly threat to personal freedoms." This is a shameless distortion of his unambiguous previous message. It reveals what has been evident to many readers all along: Burroughs was always ready with high-minded defenses of his work, which could only elicit one aesthetic response: revulsion.

Still, "Naked Lunch" serves a very valuable and reliable purpose. Get to it early enough, somewhere between the Hardy Boys and Holden Caulfield, and the fatigue and tedium will inoculate you against all sorts of intellectual malfeasance. You'll never swallow the line that obscenity is a hallmark of genius, or that the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom (usually it leads to the palace of excess, except when it leads to the hovel of incomprehensibility). Dismiss Burroughs as a pull-my-finger bore and you're ready to dismiss Matthew Barney, Damien Hirst, the Chapman Brothers, Jonathan Littell and a host of others too dull to mention.

"I am not an entertainer," Burroughs wrote in 1959. You can sure as hell say that again.

Shares