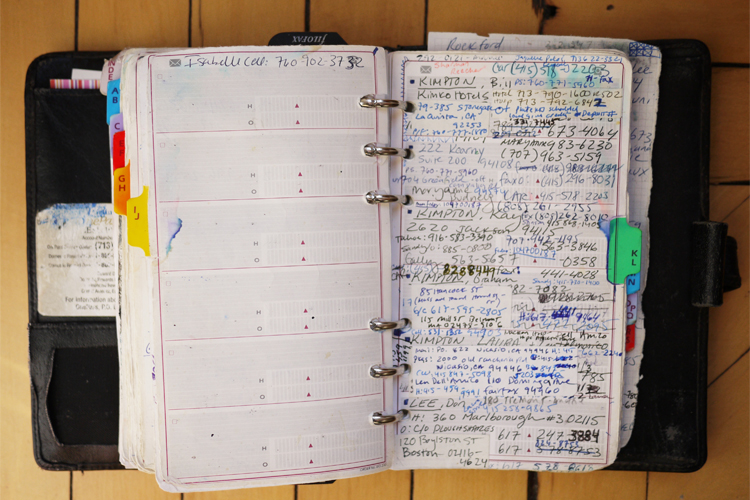

In our era of sleek, glistening, multifarious multitasking handsets, I’m still lugging around the same chubby, scuffed blue leather planner I’ve owned since around the time of Operation Desert Storm. It’s cumbersome, unsightly and not terribly functional; the address pages are falling out despite the fact that I’ve fortified their frayed binder holes with Scotch tape, and the book is so bulky that it’s often hard to cram into my purse or backpack, forcing me to leave it behind.

I fantasize about the days when I, like everyone else I know, can immediately locate that great florist I used one time in Chicago (without having to search through years of e-mail for the original recommendation); or the water park someone told me about in New Jersey, or the reasonably-priced roof repair guy we hired years ago. I long to be able to make a plan without having to say, “I’ll let you know after I check my book,” and to not have to copy out addresses and directions to bring along with me, so I don’t have to weigh myself down with it.

But whenever I consider actually buying a new device, I put it off. Partly I dread the data entry and the learning curve, but I strongly suspect that the luscious gadgetry — not to mention my new, streamlined existence — would eclipse all that. Besides, plenty of data I wouldn’t need to transfer — the blue book is bloated with dead information that is largely responsible (along with the bulky leather cover) for its ridiculous weight. By going electronic, I would shed the addresses and phone numbers of people whose names I only dimly recognize now, or not at all! — “Books, rare: Robert 480-2138″ — not to mention defunct businesses: World Gym on Lafayette Street; Nada theater on Ludlow. I would eliminate countless more entries belonging to folks I fondly recall but have been long out of touch with: previous bosses and colleagues; friends of friends; even people I was once was very close to, but whose lives disengaged from my own. If I wanted to find them, my address book would be useless — the information is hopelessly obsolete. I’d be better off looking on Facebook.

The entries of friends I’ve known longest have been endlessly amended, in microscopic writing that crawls up the sides of the pages, to record moves, marriages, breakups and career changes. When someone’s entry becomes impossibly full, I’ll paste a snippet of white label over the outdated stuff and add the new on top. These labels have accrued throughout the book like layers of old paint; if I peel one away (or if the labels fall off, as they sometimes do) I find myself glancing back through the strata of friends’ lives — old apartments, former cities, obsessive or dull or cheating mates — and each former version of their lives instantly invokes an earlier point in my own.

The dead information in my book includes, of course, the dead. The first entry under “E” is still my father, Donald Egan, who died in an accident in 1996. It’s been many years since I’ve dialed the 800-number at his Chicago law firm that family members were allowed to use, and been greeted by the oaky voice of his longtime secretary, Sally. But the numbers are still there, exactly as they were when he was reachable, and my eyes still pass over them in the course of my daily life.

My stepfather, Bill Kimpton, is still under “K,” his topmost layer a label crammed with details from MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, where he was treated for leukemia in 2000. I included his blood type, O+, along with instructions for those who wanted to donate platelets for him. Now and then I’ll glance at those details — so practical, so specific — as I turn pages on my way to someone else, and I’ll dimly recall the furor of dealing with his sudden illness; e-mailing everyone I knew with a connection to Houston in search of eligible donors; my deep conviction that it would all work out in his favor, because anything less was unimaginable.

Of course, when I go electronic I can save these meaningful pages and look at them whenever I’m moved to — probably never, or rarely. That’s how it is with my datebook pages, which I save at the end of each year, removing them from the book and sealing them in an envelope with the year written across the front in black Sharpie. A heap of those envelopes has amassed behind a row of books in a cupboard outside my office. I know what I’ll find if I look inside one: appointments scrawled and crossed out or rearranged, arrows, exclamation points, notable discoveries (“pregnant,” I remember scrawling in the winter of 2000, wanting to record the exact day I found out) — ragged textures from a scattered, labile life, all of which will be processed away when my schedule is converted to a series of efficient colored blocks.

Of course, when I go electronic I can save these meaningful pages and look at them whenever I’m moved to — probably never, or rarely. That’s how it is with my datebook pages, which I save at the end of each year, removing them from the book and sealing them in an envelope with the year written across the front in black Sharpie. A heap of those envelopes has amassed behind a row of books in a cupboard outside my office. I know what I’ll find if I look inside one: appointments scrawled and crossed out or rearranged, arrows, exclamation points, notable discoveries (“pregnant,” I remember scrawling in the winter of 2000, wanting to record the exact day I found out) — ragged textures from a scattered, labile life, all of which will be processed away when my schedule is converted to a series of efficient colored blocks.

We all know that history inheres in objects, but this seems more keenly true when the object in question unfolds over years and records their passage. Time is always invisibly seeping past, but we perceive its passage abruptly — with surprise, even disbelief. How can my kids be 7 and 9 when they were babies so recently? Keeping a physical record of the sequence of hours and days that articulate what later seem like inconceivable changes, reassures me. Even if I seldom look at those old datebook pages, they’re a physical link to the actual days whose textures they heedlessly narrate.

And my fat blue book, accreted over many years, helps to answer a question that dogs me more and more often, now that I’m in my forties and time seems to careen past: How did I get here? As long as I’m still actively using it, the book feels alive, connecting me organically to my early years in New York, the people I used to hang out with, the people I thought would be here always. The minute I put it away for good, as I surely will — probably soon — it will become an artifact: historically suggestive, but disconnected from my actual life. It feels like a big step. So I wait.

Jennifer Egan is the author most recently of “A Visit From the Goon Squad” as well as “The Keep,” “Look at Me” and “Invisible Circus.” She lives in New York.