There are many family memoirs whose stories are as enticing as Edmund de Waal’s. There are few, though, whose raw material has been crafted into quite such an engrossing and exquisitely written book as “The Hare With Amber Eyes.”

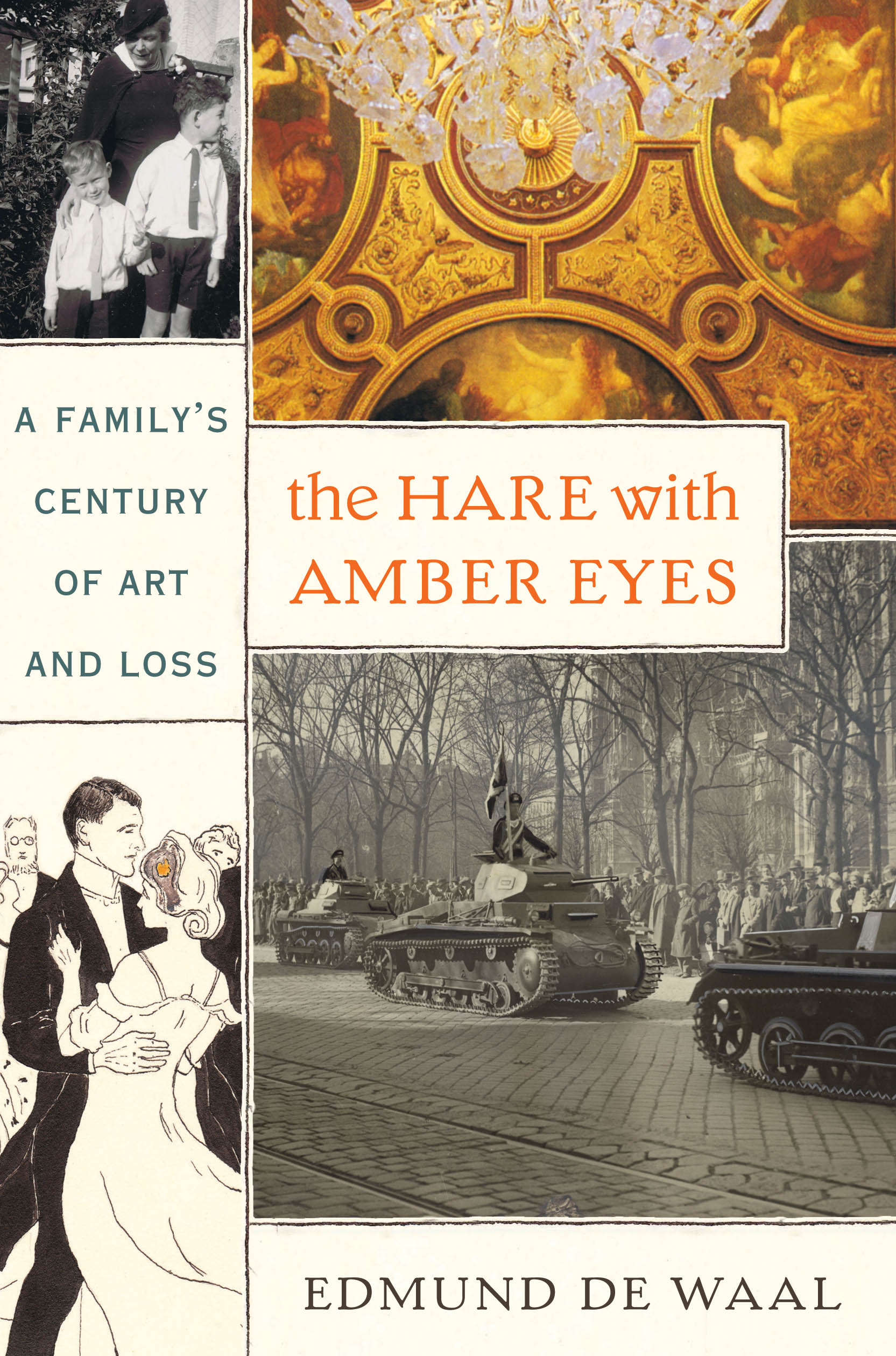

Edmund de Waal is a celebrated British ceramicist whose family on his grandmother’s side, the Ephrussi, were once mentioned in the same breath as the Rothschilds. Jewish grain exporters from Odessa, the Ephrussis had, by the middle of the 19th century, become titans of European finance; at their height, between the 1870s and the early 1900s, they dealt with governments, archdukes and royalty, had vast town houses in Paris and on Vienna’s Ringstrasse, and possessed art collections that would put many a museum to shame. By the 1940s, though, the houses had gone, the art had been broken up, and the different family members had either escaped into exile or been herded into concentration camps. “The Hare With Amber Eyes” is a delicately constructed and wonderfully nuanced investigation of that bitter decline, and of the traces of the Ephrussis’ lives that still linger in the physical fabric of the world around him.

De Waal’s memories of his grandmother’s family are scattered — just a few anecdotes handed down from his parents, and a few forgotten books. What binds him most forcefully to his forebears is a group of 264 wondrously delicate Japanese figurines, netsuke, which he inherited from his great-uncle Iggie and which have been in the family since they were bought in the 1870s by Charles Ephrussi, a fabulously urbane cousin of his great-grandfather. Beautifully crafted, intensely characterful, these objects seem to de Waal to hold within their hypnotically tactile surfaces great and enticing secrets. Tracing their journey across five generations, he finds himself plotting his way through great swathes of modern European culture and history, from Marcel Proust and Edmund de Goncourt, via Joseph Roth, to the Anschluss, the Second World War and beyond.

De Waal’s memories of his grandmother’s family are scattered — just a few anecdotes handed down from his parents, and a few forgotten books. What binds him most forcefully to his forebears is a group of 264 wondrously delicate Japanese figurines, netsuke, which he inherited from his great-uncle Iggie and which have been in the family since they were bought in the 1870s by Charles Ephrussi, a fabulously urbane cousin of his great-grandfather. Beautifully crafted, intensely characterful, these objects seem to de Waal to hold within their hypnotically tactile surfaces great and enticing secrets. Tracing their journey across five generations, he finds himself plotting his way through great swathes of modern European culture and history, from Marcel Proust and Edmund de Goncourt, via Joseph Roth, to the Anschluss, the Second World War and beyond.

De Waal’s story begins with Charles, an aesthete and collector who amassed a large and impressive collection of Impressionist paintings in 1880s Paris. Arriving in the city as a callow 21-year-old, Charles quickly established himself in the haute monde, became a familiar (and hated) figure to the socialite diarist de Goncourt, and employed Proust as his secretary (becoming in the process one of the models for Charles Swann in “A la recherche du temps perdu”). Charles it was who, in the flush of enthusiasm for all things Japanese that swept Paris in the 1870s, purchased the netsuke that now sit in de Waal’s house in south London.

One of the great triumphs of “The Hare With Amber Eyes” (the title is a description of one of the netsuke) is not just the assiduous way in which de Waal interrogates his raw evidence — scattered articles and newspaper cuttings, old paintings, forgotten buildings — but the way he summons up different eras so evocatively. In Paris, we walk down Baron Haussmann’s newly minted streets and enter the febrile world of high-society gossip. We encounter, too, the anti-Semitism that riddled Parisian society, and listen to the poisonous whispers that would grow in volume during the Dreyfus case — “this incessant hum of vilification,” says de Waal, that will see the hateful Degas break off contact with Ephrussi and Renoir become “actively hostile to Charles and his ‘Jew art.’ “

Pungent as this prejudice is in 1890s Paris, its stench becomes rank in turn-of-the-century Vienna, where de Waal travels next in pursuit of his netsuke, after they are given by Charles as a wedding present to his cousin Viktor. Here, the hatred is more naked, the attempts at assimilation by the Jewish elite more intense. As the sad and frustrated Viktor and his precocious wife Emmy negotiate their way around high society, the world turns against them. After the 1938 Anschluss that united Austria with Nazi Germany, and in one of the book’s most devastating passages, they have their possessions confiscated and their house stripped from them for use by the Gestapo. The Ephrussi bank is taken away and greedily snapped up by Viktor’s Aryan colleague of 28 years.

De Waal does not begin his book as a screed about anti-Semitism; the subject seems to sneak up on the narrative almost unawares, until it sweeps the author away, leaving him at one point crying tears of frustration and rage. Throughout, as he travels around Europe and onwards to Japan in search of the netsuke, he is careful not to submit to any sort of glib nostalgia, or swamp us with extraneous family research. He is, too, as you would expect of a potter, wonderfully tactile in his investigations, interrogating the physical feel of the Ephrussis’ different buildings, touching surfaces, assessing materials. This sensuality transmits itself also to his prose, which is beautiful to read — lithe and precise, crisp and delicate. The result is a memoir of the very first rank, one full of grace, economy, and extraordinary emotion.

Andrew Holgate is Literary Editor for The Sunday Times of London.