The bug man is only an hour late this time. He's wearing a white shirt uniform with fancy red epaulets. A professional killer, ready for the slaughter, dressed up like a Maytag repairman.

He's cordial at the door. He shakes my hand. He doesn't seem to think twice about the potential exposure. He's curt, but has kind eyes. Other days, other circumstances, I'm sure he smiles widely, his eyes disappearing into wedges. I have that same facial structure. It puts some people off.

"Honestly, now, where exactly have you seen them?" he asks.

"Honestly?" That seems unnecessary. As if I would invent this kind of trouble. Ever since the critters showed up, I've been screwed in five dimensions. Not sure who I can tell, freaked out about the fallout. I feel like I have the mark of a leper, a carrier of contagions. And nothing seems to help: This is the third time my apartment has been sprayed, and all I have to show for it is the bug man's accusation. What kind of person would make this up? And who walks around with thoughts like that? Only the stone-faced, working the front lines.

I show him a tiny one trapped on the floor on double-stick tape, a trick I learned off the Internet. I was proud of that. He nodded. "OK."

I've followed the rules and washed every piece of clothing. People eye me in laundromats. They wonder why anyone would have 12 loads. And I think the same way, full of sidelong suspicions: Who was in here before me? How safe are these washers? Was the last guy as careful as I'm trying to be now? But in the end, the accusation turns on itself: I am infested. That's not an easy thing to hear yourself say.

In the middle of his spraying, the bug man puts on safety glasses, and I wonder just how convinced he really is. Everyone's read it — these chemicals don't really work — and yet he leans into it, with his fancy red epaulets. He patiently sprays everywhere that I point.

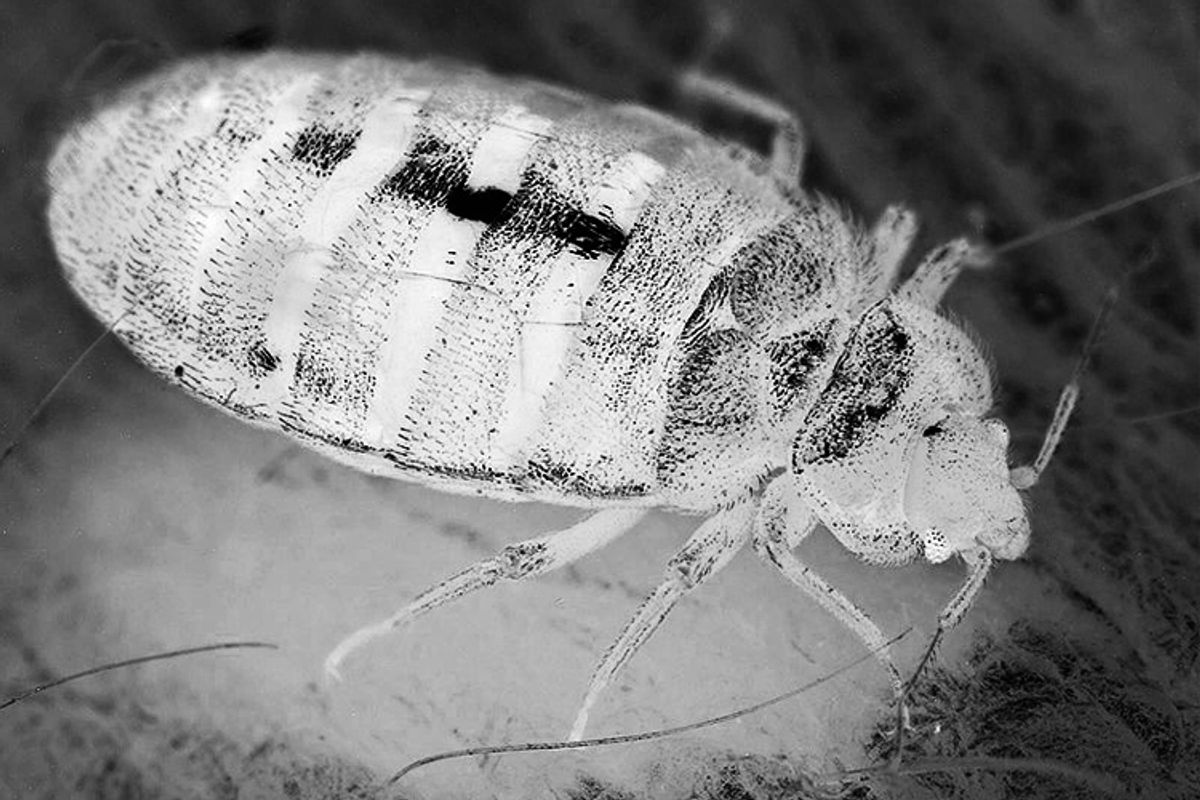

After, he shakes my hand again, and I sign his papers. Now all that's left to do is wait. Keep an eye out for the scurrying, wait for the itch. I know they're still out there. The other day, I found one in my Neti pot. So I stretch out on my white bug-proof cover, on top of my new white mattress. It's white as milk, a pure milk mattress, except for one burnt-red spot, reminding me that somehow the bloodsuckers still get through.

I review my safety measures, derived from Internet reading: every time I go out, I first disrobe at the door and change into clean clothes. Those clean clothes are kept in a twist-tied plastic bag. I stick with one pair of shoes and spray them, inside and out, with whatever harsh-smelling chemicals the hardware store is hawking.

I've had to clear out almost everything, paring down to monkish essentials. Last weekend, I dismantled my hallway bookcases, a last-ditch effort that netted 21 boxes of books. I am a reader, I've lived here a dozen years, and what we're talking about now is a fundamental shift. Lying on my milky mattress, they're what I miss most. Some of it a little dated, the German language tapes, the novels from Prague, that difficult book on the body as text. Or the text embodied. Or the body as metaphor for words on the page. I never really got that, and it's all a buggy blur now. It's not like lit theory is going to get me out of this.

After three visits from the bug man, I wonder who I can trust. The two big questions that still go unanswered: Where did they come from? And what did I do to deserve this mess?

The New York Times has been weirdly on top of this. For the past three weeks, bugs have been front-page news. Same goes for Time, Yahoo, the wire services. "Bedbugs are epidemic ... from four-star hotels to SROs."

I learned they don't care about thread counts. And they don't care how filthy my apartment might be. I haven't always lived a white-glove life, so it's good to know I'm in league with hospitals, doctors' offices and Ritz-Carlton suites. Bedbugs only ever want one thing -- just me and the blood locked in my veins.

When the word "epidemic" started getting tossed around, it was picked up from a NIH/CDC report. From a public health standpoint, what I heard the experts saying, none of this could be pegged as my fault. They're being found in record numbers, in a record number of places, and they're being carried around in the most casual way.

And as for where they come from, there's really no good answer. I live in San Francisco, one of the "infested" cities. But I was in Amsterdam and Paris earlier in the year. And in Portland and Denver before that. If it's really a travel bug, as some people insist, I still can't say what I did wrong, except open my luggage in a way that's somehow irresponsible.

From on top of my milk mattress, I've watched the panic take shape. After the quotes from public health folks, things always get a little bent. Often an infested individual asks to be anonymous, as if this were an enormous criminal conspiracy. Then again, a commenter at the New York Times claimed to have lost his job because of an infestation at home. On Yelp, a plea for advice gave way to a stream of prickly gross-outs.

The truth is, no one has found a way to avoid this — a notion that's reported with a jaunty dread. From Banana Republic to Bergdorf Goodman dressing rooms, no place is immune. But still, in every story, it's crafted the same. It's always the victims who carry the weight.

It was you who chose to walk into that store. You picked that hotel. You booked your own flight. You've made the choices that led to where you're at.

My landlord twisted the knife a little deeper: You have some iffy visitors, he said. You invite the wrong company. Whoever it is you have in your bed, they are clearly to be blamed.

Blame is what these bugs are all about. It's central to how the problem is dealt with. And as my landlord explained, the exterminator's bill would be coming my way.

"It's our policy that you're liable for bringing them in here." As long as they're only found in my apartment, I am responsible for associated costs. No neighbors have complained, and the bug man has confirmed it. With his stone face and epaulets, he invaded their apartments and pulled back their blankets while they were off at work. He didn't find any other blotches or smears, none of them hiding in my neighbors' mattress folds.

"The problem is confined to your unit," my building manager told me. And already I was thinking: Tell that to the furrier at Bergdorf Goodman.

When I called the city's Department of Environmental Health, I got some encouragement: "It's like if you left the garage door open and rats ran in. The landlord is still responsible for getting rid of the rats."

She sounded like a nice lady. She had an interesting accent. But she said she couldn't get involved in landlord-tenant disputes.

On the radio last week, an expert explained how DDT used to do the trick. He sounded sad it is no longer available and, after a big sigh, explained that nothing like it is in the pipeline either. I'd heard elsewhere that Zyklon B, the gas used at Auschwitz, used to get good results. But I can't fathom the black market bug man who'd come along with that.

No one can tell me how long this will go on. It's like my home is chronically sick. My life, too, is taking a beating. And with the news stories, pumping up fear and tripping over facts, there's the general sense of a vague lurking threat. Name your favorite scourge. Bedbugs pretty much fit.

Jon Roemer is a writer in San Francisco. His current project is Outpost19, a book/news app.

Shares