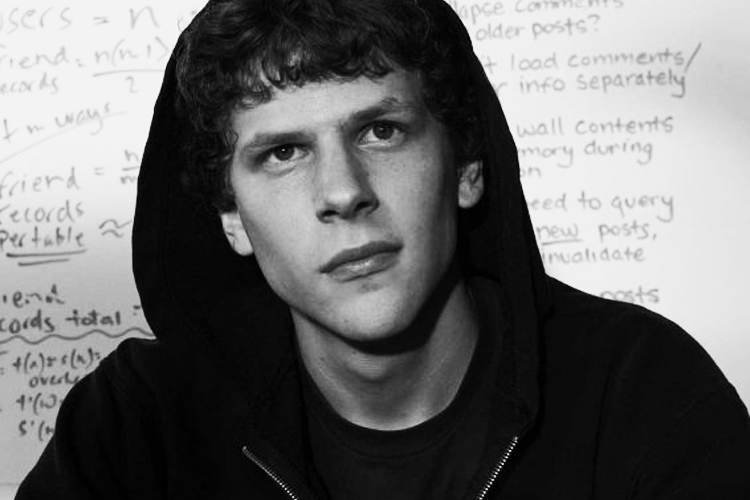

Late in “The Social Network,” Facebook mastermind Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) sits at a nightclub table listening to his erstwhile mentor, Napster founder Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake). Parker recounts how the founder of Victoria’s Secret sold the company to Limited Brands for a hefty sum five years after starting it, then watched it balloon into a global brand worth infinitely more than he got for it, and jumped off the Golden Gate Bridge to his death.

“Was that a parable?” Zuckerberg deadpans.

You bet. So, for that matter, is “The Social Network.” Like all good parables, you can apply it any number of ways. Roger Ebert, for instance, describes the movie’s virtual spaces as a chessboard and Zuckerberg as Bobby Fischer. New Yorker film critic Richard Brody describes the movie as a 21st century tale of Jewish-American tenacity and as “the latter-day successor to ‘Amadeus.'” A.O. Scott of the New York Times calls it “a movie about business” generally, not just Facebook, and an example of how Internet culture shatters class privilege. That these readings and others seem plausible — even persuasive — is a testament to the film’s concision. Director David Fincher and screenwriter Aaron Sorkin provide enough information to push the story along while leaving imaginative space for viewers to roam around in.

And in the spirit of roaming, here’s one more angle: “The Social Network” is a horror movie. It doesn’t shed a drop of blood, yet it manages to conjure some of the dread we feel when faced with a scenario — any scenario, petty or grave, fictional or real — that we are powerless to stop. It’s about the gleaming new stadiums that rise up in major cities every few years without fail, despite protests and lawsuits and complaints to the zoning board. It’s about finding out that you owe more in taxes than you expected, thanks to code changes hammered out behind closed doors by parties with deep pockets and a vested interest. It’s about revisiting a cherished stretch of public beach for the sixth or seventh year running, and finding it fenced-off and swarming with cement mixers and guys in hard hats. And it’s about how the United States avenged an attack by invading a country that had nothing to do with it.

It is about, to paraphrase a memorable Parker line, being smart enough to recognize the “once in a generation ‘holy shit!’ moment” and seize on it. But it’s also about the “holy shit!” that gets pried out of a person when he or she figures out that whole corners of reality can be torn down and rebuilt according to someone else’s whim, with no regard for law, tradition, decency or manners. When you don’t recognize any limits — and this film’s Zuckerberg doesn’t, that’s how he got so far — all of reality is virtual.

Yes, “The Social Network” is about Facebook, and business, and genius, and tactics, and the class system, and filmmakers’ undying obsession with “Citizen Kane.” (The conceit that Zuckerberg was driven by the need to impress a girl who jilted him combines two iconic elements from “Kane” — the sled, and the accountant Bernstein’s monologue about seeing that beautiful girl on the ferry.) This is Zuckerberg’s story — not the real-world Zuckerberg, mind you, but the fictional construct who happens to bear his name. (The girl-who-got-away is Sorkin’s invention; real-world Zuckerberg has been involved with the same woman for years.)

But “The Social Network” is also the story of the characters whose lives are touched — manhandled — by Zuckerberg. And if you view it through the horror movie lens, it seems more their film than Zuckerberg’s. The Facebook founder is shown almost exclusively in relation to the other characters — how they met him, what they thought of him, what he allegedly did to them. The other characters change as a result of encountering Mark Zuckerberg. But Zuckerberg, as far as we can tell, doesn’t learn or change (though he may have at least one major regret at the end). He’s like Kane in that sense, or Daniel Plainview in “There Will Be Blood,” or Mozart in “Amadeus.” He’s also a kind of a modern, white-collar version of a horror movie monster — a Lecter, a Freddy Krueger; a force against which the other characters are tested; a being whose relentlessness and technical genius overwhelm (and in some cases destroy) the lives they touch.

Zuckerberg isn’t the focus of the film’s more wrenching emotions, because he either doesn’t feel big feelings or (more likely) keeps them under wraps. His former partners do most of the feeling and suffering: Zuckerberg’s partner Eduardo Saverin, especially, but also the three smug, entitled students for whom Zuckerberg is supposed to be building a site called HarvardConnection while he’s secretly building Facebook: Divya Narendra (Max Minghella) and the Winklevoss twins (Armie Hammer, playing two characters with help from special effects). When Saverin and Zuckerberg score with a couple of girls in a bar bathroom, Fincher shows us Saverin’s horny fumblings in close-ups, but keeps the once-jilted, now gun-shy Zuckerberg hidden in his own stall, showing only the young woman’s high heels and the young man’s flip-flops — a striking choice in a movie that’s supposedly “about” Zuckerberg.

Brody’s belief that “The Social Network” is a portrait of genius is correct. But the movie is also (not mutually exclusively) a portrait of what the irresistible force of genius — what irresistible force, period — does to others; not just the force of Mark Zuckerberg, but that of the charming cokehead Sean Parker, who knows how to light up a room and leave it wanting more. Parker is 25 minutes late to his first meeting with Zuckerberg, Saverin and his girlfriend. Saverin takes this as a sign of disrespect and flakiness; Zuckerberg sees it as evidence of Parker’s genius and isn’t bugged in the slightest. Parker shows Zuckerberg how to look the part of a hard-partying Palo Alto go-getter, and helps him get the venture capital money that the small-potatoes Saverin can’t bag. But he also teaches him how to amp up what might be called the Minstrelsy of Genius: showing up, for example, at an investors’ meeting in pajamas and a bathrobe; insulting one of the investors, a man who once got Parker fired; then going home to find that the investors, even the insulted one, were deeply impressed by him, not just because of his ideas, but because they expect high-tech visionaries to act like smug jerks who think the world is a huge rec room. How does Zuckerberg get away with this? The same way he gets away with all the other minor and major outrages he commits: because he acts like the sort of person who can get away with it — like a benighted person to whom the rules, however you define them, don’t apply. (When a peevish plaintiff’s attorney asks in deposition whether he has Zuckerberg’s attention, Zuckerberg coldly replies that he’s giving the matter as much attention as it deserves, which isn’t much, then adds, “Does that answer your condescending question?”)

One person’s genius is another person’s trauma, and there’s plenty of trauma on display here. “The Social Network” is about everything you’ve heard that it’s about, but the umbrella arching over all those readings is the pain of being left out, left behind, run over. It’s a depiction of impotent rage in the face of forces that dramatically altered reality without warning or permission, by treating certain bits of received wisdom as theories that can be disproved or ignored: No one is above the law, the rules apply to all of us, there’s a way things are done, there’s such a thing as decency, etc. What seemed unlikely, even impossible, just happened, became real and irrevocable because some people thought it was a grand idea, did whatever they had to do to make it real, and refused to recognize what their opponents thought were impediments. Think of Bugs Bunny explaining that he can defy the law of gravity because he never studied law. Or Michael Corleone in “The Godfather” asking, “Where does it say that you can’t kill a cop?” — a rhetorical question that presupposes that prohibitions don’t exist if you refuse to recognize them. Or Karl Rove figuring out that the most effective way to attack a bona fide war hero during the 2004 presidential election was to paint him as a sissy who didn’t deserve his medals. (Even if you despised Rove, you almost had to admire the sheer nerve and originality of that attack — a “Matrix” moment for sure.)

The film observes all this with what could be described as scientific detachment — as if what we’re seeing on-screen is a scrolling display of program code. It renders no verdicts and comes to no conclusions; it just shows a certain state of affairs that both it and the audience know to be true. The movie’s title, “The Social Network,” describes the opposite of Hobbes’ State of Nature: a latticework of laws, traditions, social bonds and moral codes that binds one person to another and keeps civilization humming along. If you can’t get with the program, rewrite it. It’s all just ones and zeroes.