As we lurch ever further in time from the peak moments of the financial crisis, the act of revisiting the momentous events of September 2008 is starting to take on an uncanny hue. I remember all too well living through those tumultuous events, buffeted by the cascade of news shockers reshaping the face of Wall Street, the drastic government zigzags -- bail out Bear Stearns, but let Lehman fail! -- the free-falling stock markets, the imploding global economy. But returning to the scene of the crime two years later, the adrenaline rush is gone. What happened then is now history: Instead of breaking news tidbits that move markets in nanoseconds, we get 500-page tomes rehashing narratives that sometimes feel a bit moldy.

Which is not to say that what happened then isn't relevant to the here and now. The results of the election taking place today will in no small part be influenced by the fallout from how the Obama administration handled the aftermath of the crisis. As we look back at the days of yore, the same questions keep coming up: How could it have been handled differently? And would this election be any different if it had? When, last Friday, the mailman delivered to my house the newest entry in the financial crisis forensic autopsy genre, Greg Farrell's "Crash of the Titans: Greed, Hubris, the Fall of Merrill Lynch, and the Near Collapse of the Bank of America," that's precisely the question I hoped might be answered.

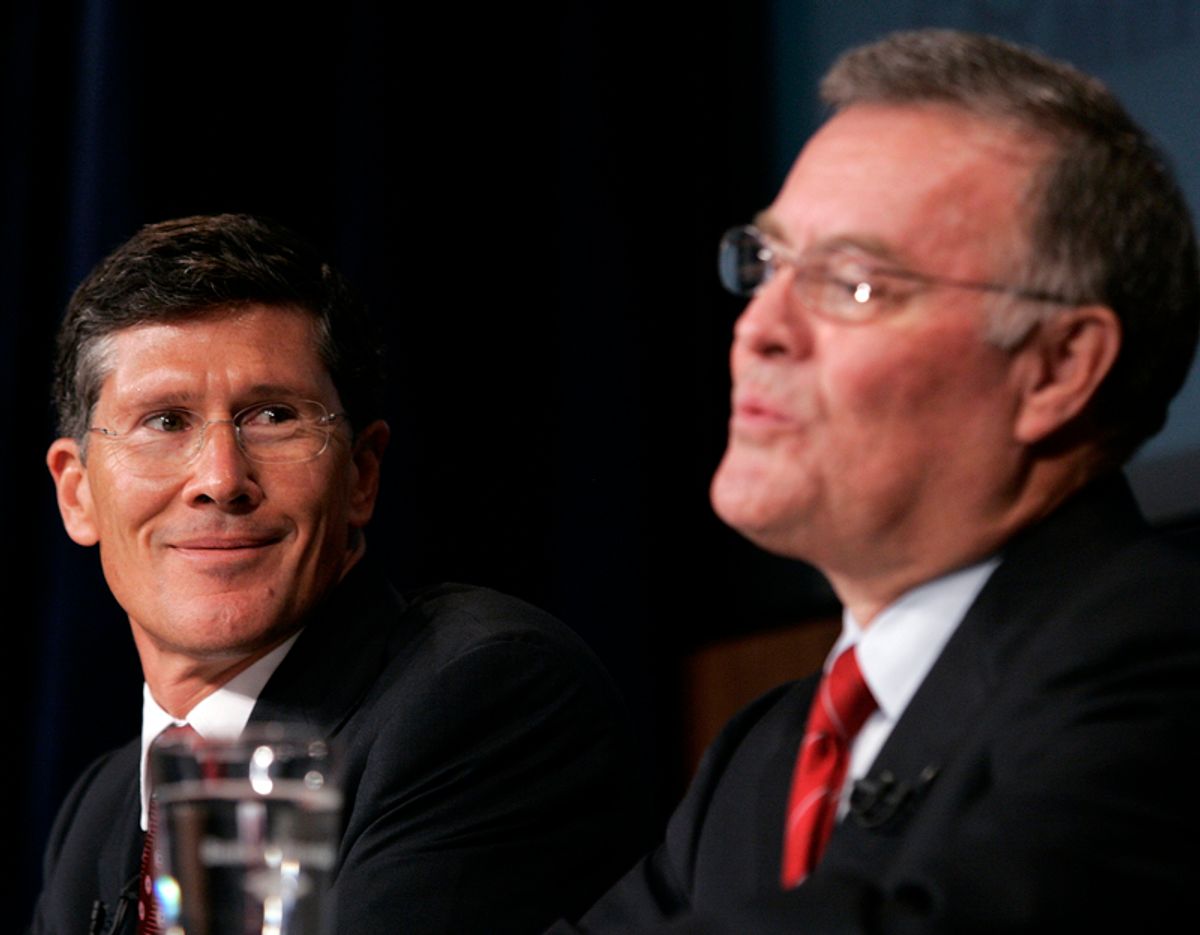

After the first couple of hundred pages I thought I would be disappointed, even though Farrell's account is eminently readable and convincing. Farrell devotes surprisingly little space to the role of government officials and policy, either in terms of how the conditions for misbehavior on a globally disruptive scale were created, or how the catastrophe was managed as it happened. Ninety-five percent of action detailed in "Crash of the Titans" takes place within the corporate confines of Merrill Lynch and Bank of America. Hank Paulson and Tim Geithner make cameo appearances; the real focus is on the executives of the two companies -- Merrill Lynch CEO Stan O'Neal, his successor John Thain and Bank of America CEO Ken Lewis take center stage, followed in the wings by a couple dozen other supporting corporate players.

What results is a you-are-there blow-by-blow account of how Merrill Lynch executives came to grips with the mortgage-securities bomb threatening to blow up the company, resulting, first, in the speedy replacement of Stan O'Neal with Goldman Sachs veteran John Thain, and second, in the hastily concluded sale of the investment bank to Bank of America.

The larger contours of the story are familiar. Well after the rest of Wall Street had already begun to abandon the business of creating, selling and trading dodgy mortgage loans converted into complex securities, Merrill Lynch was still merrily speculating in mortgage-backed securities constructed out of the dregs of the dregs -- the worst loans made at the height of the boom. When boom turned to bust, Merrill Lynch's huge profits flipped to equally monstrous losses with a speed that took everyone involved completely by surprise. If Thain (or actually, as Farrell makes clear, company president Greg Fleming) had not been able to orchestrate a shotgun-sale to Bank of America on the September weekend when all hell broke loose, Merrill Lynch would almost surely have followed Lehman Brothers into bankruptcy ... or a government bailout.

That's the big picture. But what emerges from Farrell's account is a grittier story zeroing in on the motivations driving the individual players -- a classic tale of self-interest, in which chances for corporate advancement and the desire for a big bonus trump everything else. There's nothing of great surprise to be learned here -- it surely isn't newsworthy that bankers are motivated by money. But there's great value to be gained in the detail that Farrell reveals, particularly as it applies to one of the storylines that most outraged the general public in 2009 -- the single-minded focus that Merrill Lynch executives, from Thain on down, devoted to getting their bonuses, even as the economy was crashing and their own firm was losing billions of dollars a quarter. Merrill Lynch was in such bad shape that the federal government was forced to inject an additional $20 billion into Bank of America after the merger to keep the colossus from sinking. To the ordinary American, the greed on display was not just appalling, but unthinkable.

And it's at this point that we understand why Farrell doesn't dig deep into the government's role. Because from his perspective, the key to understanding the financial crisis hinges upon understanding the incentives created by Wall Street's compensation practices.

...The whole reason everything almost came crashing down in 2008 was twenty-five years of nonstop focus on bonus checks, on compensation. Why did Lehman Brothers go out of business? Because their people kept doing real estate deals long after the market had turned. It produced bigger bonuses for them. Why did AIG keep selling those foolhardy insurance police on CDOs? Because it was easy money and led to bigger bonuses. Why did Merrill Lynch need to be saved in the first place? Because O'Neal let his guys run wild in the CDO market so they all could get bigger bonuses. Bank of America could never have bought Merrill Lynch if the people up there hadn't been so obsessed with their own bonuses that they were blind to the dangers of what they were doing. The people at Merrill Lynch came crawling to Charlotte because of their own self-inflicted wounds. The whole reason John Thain worked for Ken Lewis, and not the other way around, was that bonus culture they had up there in New York. And even Thain, with all his degrees from Harvard and MIT, couldn't see it. That's what twenty-five years on Wall Street would do to a man.

I am as guilty as anyone, perhaps even more so, of attempting to explain the genesis of the financial crisis in terms of ideology and politics, as a consequence of the triumph of deregulatory ideology. I always thought that the outrage over the bonus scandal was overblown, because to me, the far more important story was how a deregulated Wall Street had precipitated a huge financial crisis, and the primary challenge for policymakers was to figure out how to avoid another Great Depression and make new rules for the financial sector. I found the revelations of bonus greed in the spring and summer of 2009 highly annoying, but didn't feel the same kind of outrage that the general public and politicians were reveling in, because my primary emotion at that time was a sense of relief that an even greater disaster had been averted.

In retrospect, maybe I should have been angrier. Because the quest for those bonuses was the primary match that lit the overall conflagration, that encouraged financial sector lobbyists to push for the rules to be weakened, that led CEOs to give a free hand to the derivatives generating such huge revenues. If we want to understand some of the anger driving Americans to polls today, at least part of it must derive from the fact that greedy Wall Street financial institutions' executives broke the economy, and didn't get punished for it. Far from it, their industry was kept on life support at taxpayer expense.

A very simple story, when all is said and done.

Shares