History does not repeat itself, although sometimes echoes of the past seem remarkably familiar to us. Each event in history is, however, unique, just as every person is. Generally speaking, though, we humans (including historians like me) do not hesitate to wonder if history is repeating itself: we ponder whether the recession will be another Great Depression, Afghanistan is another Vietnam, the 2012 presidential election will be another 1996, Obama is another Jimmy Carter, Obama is another Bill Clinton, and, my favorite, whether Obama is another Lincoln (case in point: Garry Wills’ essay on Obama’s Tucson speech in the latest New York Review of Books). Maybe what we mean, or what we think we mean, is that there is sometimes a resemblance between the past and present, something a bit more reminiscent than just a vague feeling, as we all get every once in a while, of déjà vu. When those similarities strike us, we wonder if history is repeating itself, for good or ill.

Lately, I’ve been trying to put Sarah Palin into a historical context. It’s not easy to do. She continues to attract public and media attention, even while her national approval ratings keep falling. Nevertheless, the media and her most fervent supporters are convinced (or hopeful) that she’ll make a run for the presidency in 2012. If that is indeed what’s she planning, I think we must admit that she is approaching the possibility of a Republican nomination in a very different manner than any candidate I can remember in my lifetime (six decades and counting). Her daily presence on television, in newspapers, on the Internet and Twitter, her reality show, her job as a commentator for Fox News, her two books, her surrogate manifestations on TV (Bristol Palin on “Dancing with the Stars”), and the coverage she gets for nearly every word she utters all add up to a truly unique path to high national office — if that, indeed, is what she’s after. From another perspective, all this kinetic publicity is certainly accomplishing one thing, even if Palin decides not to run for president: she raking in a bundle of money.

The unusual, even startling, nature of her daily presence in our lives — actually in my life, since I am a news hound besides being a historian — started me thinking about whether there are any examples from the past of American politicians who resemble Palin in any way. Actually I came up short at first, since Palin is using twenty-first century technology to her greatest advantage as a politician and as a celebrity, far more so than any other political figure in our history, and that makes her a real product of our own times. She’s like the first Britney Spears or Paris Hilton of American politics.

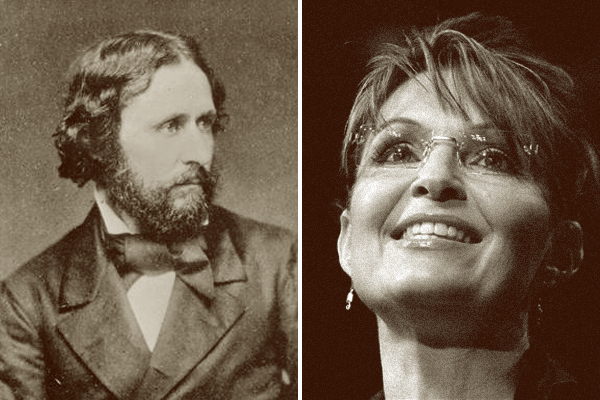

Nevertheless, my thoughts did turn to John C. Frémont, a fellow out of American history that in all likelihood you’ve never heard of (unless you happen to live in Fremont, California). Frémont was the first presidential nominee of the Republican Party — yes, Sarah Palin’s Republican Party — in 1856. Today he’s forgotten, but in the mid nineteenth century he was probably the most famous man in the nation, an explorer of the West and an army officer who was hailed as a great hero. In other words, Frémont, like Palin, was a celebrity as well as a politician.

But there the apparent similarity pretty much ends. Unlike Palin, Frémont did not emerge out of nowhere onto the national scene. From the late 1830s to the late 1840s, Frémont led or participated in several topographical and scientific expeditions that explored the vast unknown terrain (at least unknown to most whites, except fur trappers and other “mountain men”) that lay between the Mississippi Valley and the Pacific Ocean. Like the more famous Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who had made their famous trek to the Pacific from 1804 to 1806, Frémont was a trailblazer, a man who in his own lifetime was credited with opening up the West for settlement. By the time he ran for president in 1856, he was known as “The Great Pathfinder.” His earlier achievements as an explorer, as a soldier who helped to win California from Mexico, as a man of destiny who made a fortune in the California Gold Rush — all these things turned him into not only a hero, but a popular celebrity. Like Palin, who is hard at work establishing her status as a celebrity, Frémont did not look to any previous political experience (he had none) to boost his campaign for the presidency. Instead, he let his fame, his celebrity, do that for him. At age 43, he would have been the nation’s youngest president up to that time if he had been elected.

Yet most of the key elements in Frémont’s life and career make him look nothing like Sarah Palin. For one thing, Frémont was refined and sophisticated (he spoke French fluently; his father, Jean Charles Fremon, was a French émigré and a ne’er-do-well who dropped the final t in his last name to hide from the law); for all his wilderness exploits, Frémont did not consider himself “ordinary,” as Palin makes herself out to be. He knew he was exceptional, and he reminded those around him of that fact with unfailing regularity. For another thing, he was brave, intrepid, determined — although occasionally these virtues fed an impetuosity that led him into numerous debacles and some outright failures. But like the mountain men who admired him (Kit Carson was among them), Frémont loved nature, adventure, and hard work. One frontiersman, Alexis Godey, praised his “daring energy, his indomitable perseverance, and his goodness of heart.” Yet, just like those fur trappers and scouts, Frémont at heart — no matter how much goodness resided in it — was a loner. The historian Richard S. Dillon even calls Frémont a “maverick” (precisely what you-know-who calls herself). But Frémont, it would seem, was at least a better shot than Palin. He could, according to his biographer Allan Nevins, “kill a weasel at twenty paces with a sightless pistol.” It took Palin five shots with a high-powered rifle and a telescopic sight to bring down a caribou during an episode of “Sarah Palin’s Alaska” on TLC, even though her father kept telling her she was shooting too high (a tipoff that she’s not exactly Annie Oakley when it comes to using a long gun).

* * *

Born in 1813 in Savannah, Georgia, Frémont later studied at the College of Charleston, from which he received a bachelor’s degree. In the early 1830s, he took to the sea as a mathematics instructor for the U.S. Navy; later that decade he received a lieutenant’s commission in the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, working with the famous French scientist Joseph N. Nicollet, a civilian employed by the federal government. In 1842, Frémont led the first of five expeditions searching for an overland route from the Mississippi to the Pacific. Each of these expeditions nearly ended in disaster, sometimes due to Frémont’s errors in judgment, other times because the elements — particularly blizzards in the Rocky Mountains — blocked passes and forced the parties to find the easiest and quickest path to safety. During his fourth expedition in 1848, Frémont’s stubbornness resulted in the death of ten men who either froze or starved to death before a rescue party found them and led the survivors south to Taos, New Mexico. Earlier, after Mexican authorities ordered him to leave California, Frémont and a small force of armed men returned to the Sacramento Valley and participated in the Bear Flag Revolt on the eve of the U.S-Mexican War. He later admitted that he acted without orders from Washington (going rogue?), but with news that the war had begun, Frémont received a commission as a lieutenant colonel of a mounted battalion and orders from a U.S. Navy commodore to serve as governor of California. For this, Frémont was placed under arrest by General Stephen Kearny, his superior officer in California; a court martial found him guilty of mutiny and disobedience. Although President James K. Polk tried to circumvent the court’s ruling, Frémont submitted his resignation from the army and returned to California. There his luck turned, and he made a fortune during the California Gold Rush.

Frémont turned to politics in late 1849, when, after California was admitted to the Union, he was elected the state’s first U.S. senator as a “free-soil” Democrat — that is, a Democrat who believed that slavery should be excluded from the western territories. When his term as over and he ran for reelection, the state legislature chose a proslavery Democrat instead. By 1856, when the sectional conflict between North and South over slavery began to tear the nation apart, Frémont — whose name was well known in every American household — made known his strong stand against the expansion of slavery, and he won crucial support from Northern free-soil Democrats, Whigs, and rising members of a newly formed political party, the Republicans. The new party leaders could not resist the luster of Frémont’s heroic reputation, his handsome face, and his stately demeanor. Frémont’s image was perfect for the fledgling Republican Party of 1856. He proclaimed, in a statement sizzling with clarity, that he was “hostile to slavery upon principle and feeling.” Frémont accepted his nomination by issuing a statement of about 300 words that read, in part: “Nothing is clearer in the history of our institutions than the design of the nation, in asserting its own independence and freedom, to avoid giving countenance to the extension of slavery.” He then pledged himself to resist the extension of slavery “across the continent.”

This much Americans do know about Frémont: he did not become president of the United States. He was vilified in the South as a “Frenchman’s bastard” (his mother and father did not marry until after his birth) and, falsely, as a Roman Catholic. Although he won a majority of Northern votes, he lost to James Buchanan, who became the fifteenth president (Buchanan: 1.8 million popular votes, 174 electoral votes; Frémont: 1.34 million popular votes, 114 electoral votes). The loss, however, was not an embarrassment. The new Republican Party, the nation’s first truly sectional party, could hold its head high, having won significant support across the free states. Frémont was disappointed by his defeat, but he made a very good showing in the election.

Yet further disappointments and disasters awaited him. During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln — the Republican Party’s first candidate to win the presidency — appointed him a major general in command of the Department of the West, with headquarters in St. Louis. The situation in Missouri, a crucial border state that remained in the Union, was near bedlam, with Northern and Southern sympathizers violently vying for control of the slave state. In August 1861, Frémont put his antislavery principles to work when he issued an order for the limited emancipation of slaves in Missouri. Lincoln was livid. Frémont had acted entirely on his own (again, going rogue), and the president tried to persuade his general to rescind the order. Frémont refused. Then, in an act of pure arrogance or utter cowardice (depending on your point of view), Frémont sent his wife Jessie Benton Frémont, the daughter of a former U.S. senator and congressman from Missouri, to Washington to plead his case to Lincoln. The president, in a rare recorded moment of utter rudeness, refused to offer her a chair and sarcastically said to her face: “You are quite a female politician.” Insulted, Jessie fled the White House; if she hadn’t, Lincoln probably would have thrown her out. The next day the president directly ordered General Frémont to rescind the emancipation order. On November 2, after hearing reports of widespread corruption and fraud among Frémont’s headquarters staff, and dissatisfied with the military blunders that the major general kept making in Missouri, Lincoln relieved Frémont of his command.

Although political pressure forced the president later to reinstate the general and place him in command of a Union force in the Shenandoah Valley, Frémont’s bad luck and ineptness once more haunted him. He was roundly defeated twice in the Valley by the talented — and now legendary — Confederate general, Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, in the spring of 1862. A few months later, Frémont resigned his commission and sat out the rest of the war in New York City. In 1864, he ran again for the presidency, nominated this time by a group of Radical Republicans who liked his brand of antislavery politics, but he withdrew from the race and decided not to challenge Lincoln when the president dismissed one of Frémont’s political enemies, Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, from the cabinet.

Frémont spent the rest of his life in obscurity. After the war, he hoped to regain his wealth — which he had lost over the course of the two decades following the California Gold Rush — by investing in harebrained railroad schemes and other unprofitable ventures. By the early 1870s, he was almost entirely destitute. President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed him governor of Arizona Territory in 1878; nevertheless, land schemes and mining failures forced him to resign the post. When he wrote and published his memoirs in 1886, he hoped to pull himself out of poverty, but the book sales were disappointing; he and Jessie remained on the edge of poverty. In 1890, Congress benevolently granted him an annual pension of $6,000. Later that year, he died in New York of peritonitis.

* * *

As you can see, Frémont’s life was — to the greatest extent — very different from Sarah Palin’s. Even so, a slight glimmer, a speck of an idea, still enticed me to think about their similarities, even if the resemblances seemed on the surface to be rather fleeting.

In the first place, both share an affinity for nature and the outdoors. On one episode of her reality show, Palin remarked: “You have to respect the elements out here. Mother Nature always wins.” Her show features her mostly engaging with Alaska’s majestic outdoors (although many of the situations, despite the “reality” tag, appear staged): she’s been filmed hunting, fishing, hiking, skiing, rock climbing, camping out (with Kate Gosselin and her children, which turned into a wonderfully delicious mess), rafting, kayaking, and doing numerous other activities that really are nothing more than weekend participation sports. Unlike Frémont, Palin is not a pathfinder. She simply likes outdoor sports, or so we’re led to believe. Frémont, to his credit, encountered bears and other dangerous animals in the wild at closer distances and in far more dangerous circumstances than Palin ever has done. In one fantastically revealing moment on her show, Palin asks, as she paddles furiously on a raft plunging through white water, “How come we can’t ever just be satisfied with tranquility?” Deep down, she’d rather be at home, safe and warm, but sometimes you have to do certain things to make a buck.

In the second place, Frémont considered himself an outsider and acted the part of a loner, just as Palin does. Even Lincoln complained about Frémont’s insular qualities. In Lincoln’s opinion, Frémont made the “cardinal mistake” of isolating himself and forbidding anyone (other than his wife) to see him. As a result, said the president, “he does not know what is going on in the very matter he is dealing with.” Many Americans had the same opinion about Palin when she resigned as governor of Alaska — a job she claimed to love — because, as she explained in “Going Rogue: An American Life,” the first of two books she’s written, “I wanted to be challenged to serve the state better.” Self-consciously styling herself as an outsider, she further explained that she really didn’t care what anybody else thought about her decision to resign:

“I knew resigning was the right thing to do, the same way I had known it was right to run for mayor [of Wasilla], right to take on the party at the AOGCC [Alaska Oil and Gas Conservation Commission], right to run for governor, and right to say yes to John McCain. I knew we had just done the right thing for Alaska.”

Apparently, other Alaskans — glad to see her out of their state’s politics — agreed as they expressed their disapproval of her in one poll after another. Palin, for all her media exposure, still acts the outsider. While she’s the darling of Fox News, you’ll never see her being interviewed on MSNBC, CBS (a pox on Katie Couric and David Letterman!), or Jon Stewart’s “Daily Show.” Having long complained endlessly about the “lamestream” media, she even expressed disappointment that the weather was fair on the day she announced her resignation as governor; she had hoped that nasty weather would have “slimed” the attending reporters.

As this example alone suggests, Palin has demonstrated an immense lack of judgment that parallels the whopping mistakes Frémont made repeatedly in his lifetime, not just as a politician or as a general, but also as an explorer — his greatest claim to fame. In the winter of 1853-1854, Frémont led his final expedition across the Rocky Mountains, and, almost predictably given the man’s hard luck, he and his men nearly starved to death while they plodded through blizzards; finally, they retreated to Utah and saved themselves from utter destruction. Frémont declared that “the Mormons saved me and mine from death by starvation.”

For Sarah Palin, such mistakes in judgment have also become readily apparent to her enemies, if not her fans. The most recent example was the timing of her video in response to media criticism of her having used a crosshair symbol on her website to target Gabrielle Giffords’s congressional district during the 2010 campaign; Palin foolishly decided to run the video on the same day, January 12, that Tucson organizers had scheduled a memorial service for the victims who had fallen during the assassination attempt made against Giffords four days earlier. It was a blunder truly worthy of John C. Frémont.

Frémont — like Palin after him — carefully forged his public image for his greatest gain and to satisfy his prodigious ambition. “The Great Pathfinder” did not lack intelligence (nor does Palin, despite her many attempts to convince everyone that she’s anti-elite and an anti-intellectual). However, it’s unlikely that Frémont ever would have used a spurious word, like “refudiate,” as Sarah Palin once did on Twitter, nor is there any record of him blurting out “WTF,” as Palin did in a post-State of the Union interview last week (apparently her use of the acronym was meant as an intentional pun on the president’s phrase, “Winning the Future”). Frémont wrote well and spoke clearly, although his wife became a silent co-author of his reports and memoirs. One also suspects that ghost writers (or, at the very least, sedulous editors) helped to get Palin’s words on paper for her two books. Frémont never imagined that the future would forget him as thoroughly as it has or that his legacy would become largely unknown among Americans. He hoped for the same rewards — fame and fortune — that Palin is currently reaping. He got the fame, before he discovered how fickle it could be, and he even made a fortune, although he lost it for reasons that were mostly his own fault. Like Palin, though, Frémont fully understood that fame can sometimes bring a greater bonanza than mere celebrity or mounds of money. Celebrity got him the Republican nomination in 1856. And it’s quite possible that Palin’s relentless campaign of media over-exposure is calculated to give her the same thing in 2012. If so, she’s probably more than a little worried about her steadily declining approval numbers in the polls.

Throughout his life, Frémont remained sensitive to slights and insults, always ready — perhaps too ready — to defend himself, and he persisted in being recklessly self-confidence, sometimes dangerously so. Palin has shown many of the same tendencies. Her assumption that the Tucson tragedy was all about her made many Americans cringe. Frémont aspired to greatness; Palin’s insistence that she’s simply an ordinary hockey mom or Mama Grizzly or whatever she’s calling herself lately implies that she recognizes that greatness is either something she doesn’t want or is beyond her reach.

More significantly, Palin appears to suffer from the same character flaws that held Frémont back again and again. One of the most pronounced was a lack of stamina. That fault is ironic, if only because Frémont tirelessly climbed mountains and forded rivers and braved the chill of ice and snow with great determination. If her reality show is any true measure of the woman, Palin also is indefatigable when it comes to mushing a dogsled, salmon fishing, or tramping across Alaska’s tundra. Yet they both share a proclivity to quit. Frémont did so time after time when he resigned from the army on multiple occasions, gave up his presidential bid against Lincoln in 1864, and quit in disgrace from the governorship of Arizona Territory. So far, Palin’s greatest public moment as a quitter has been her resignation as governor of Alaska. In her resignation speech, she said:

“Life is too short to compromise time and resources and though it may be tempting and more comfortable to just kind of keep your head down and plod along and appease those who are demanding, hey, just sit down and shut up. But that’s a worthless, easy pass out. That’s a quitter’s way out.”

Of course, it’s hard to know what she meant, since she was announcing her resignation at that very moment, which seemed very much like the quitter’s way out. But in her attempt to make people think that by quitting she was not quitting, she revealed that there is some underlying flaw, a not entirely hidden blemish, within her that makes her think it’s okay to throw in the towel — just so long as she can rationalize her actions to her own satisfaction. “I knew,” she writes in “Going Rogue,” “I could just hunker down and finish out a final, lame-duck year in office — but I’m not wired for that.” Those are the words of someone who lacks what it takes to get through tough times, no matter how often she’s paddled a kayak through white water.

Physical courage or endurance differ from the kind of stamina I’m talking about. What I think Palin lacks (as did Frémont) is true moral courage — an attribute that the late Robert F. Kennedy defined so well:

“Few men are willing to brave the disapproval of their fellows, the censure of their colleagues, the wrath of their society. Moral courage is a rarer commodity than bravery in battle or great intelligence. Yet it is the one essential, vital quality of those who seek to change a world which yields most painfully to change.”

Enough is enough, as Palin says in “Going Rogue.” I must confess that my comparison of Frémont and Palin is, after all, a stretch. When a colleague heard that I was writing this posting, he cried out: “Poor Frémont will be spinning in his grave.”

I understood what he meant. Frémont, for all his faults still deserves to be remembered for his many accomplishments. And historians and biographers are generally in agreement that his courageous explorations through the West, which added to the nation’s scientific knowledge of what lay beyond the Mississippi River, the Great Plains, and the Rocky Mountains, were formidable achievements. What’s more, they agree that Frémont put principle first when it came to slavery and stood as a true hero in the fight against the South’s “peculiar institution.” While those successes did not necessarily make him a great man, he remains an important figure in American history. For all we know, Palin’s greatest achievements may still lie ahead of her. Only time will tell.

There is, however, one thing more that I think Frémont and Palin share: they are both American originals. They stand out for being different and remarkable. American originals, like Frémont and Palin, always march to a different drum, constantly find themselves in scrapes and controversy, make headlines and great news copy, prefer always to face West (or northwest), and spring up without warning out of the nation’s rich soil, like a rare Jack-in-the-Pulpit in the middle of a dense forest. They amaze us and befuddle us. American originals have left indelible marks on our nation’s fabric; sometimes those marks are stains, sometimes they form intricate, captivating designs. Whether you love or hate her, Sarah Palin — like John C. Frémont — is a true American original.

It’s just a little too easy for progressives to make fun of Palin, dismissing her malapropisms, questioning her intelligence, making fun of her Fargo accent (but, gosh, she does sometimes sound like Margie, the lovable cop in the Coen brothers’ movie), gloating as her popularity tanks in the polls, and predicting that she can’t possibly capture the Republican presidential nomination in 2012. I, for one, am reluctant to write her off. Yet, like Frémont, she frequently is her own worst enemy. Trying to emphasize how much she truly loves the Alaska outdoors, she said on her reality show: “I’d rather be doin’ this than in some dusty old political office. I’d rather be out here being free.” If she’s not careful, she just might get her wish.