An orbiting NASA telescope is finding whole new worlds of possibilities in the search for alien life, including more than 50 potential planets that appear to be in the habitable zone.

In just a year of peering out at a small slice of the galaxy, the Kepler telescope has spotted 1,235 possible planets outside our solar system. Amazingly, 54 of them are seemingly in the zone that could be hospitable to life -- that is, not too hot or too cold, Kepler chief scientist William Borucki said.

Until now, only two planets outside our solar system were even thought to be in the "Goldilocks zone." And both those discoveries are highly disputed.

Fifty-four possibilities is "an enormous amount, an inconceivable amount," Borucki said. "It's amazing to see this huge number because up to now, we've had zero."

The more than 1,200 newfound bodies are not confirmed as planets yet, but Borucki estimates 80 percent of them will eventually be verified. At least one other astronomer believes Kepler could be 90 percent accurate.

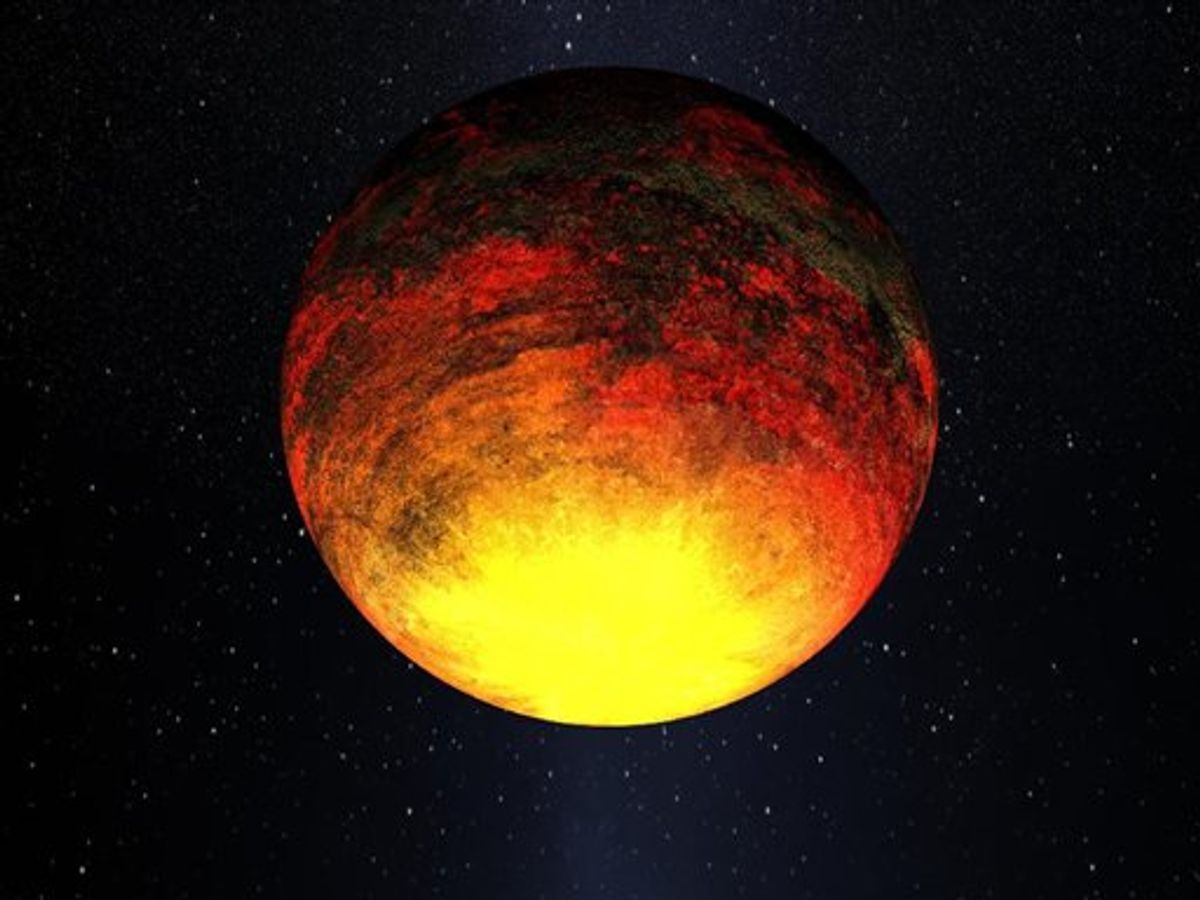

After that, it's another big step in proving that a confirmed planet has some of the basic conditions needed to support life, such as the proper size, composition, temperature and distance from its star. More advanced aspects of habitability such as specific atmospheric conditions and the presence of water and carbon require telescopes that aren't built yet.

Just because a planet is in the habitable zone doesn't mean it has life. Mars is a good example of that. And when scientists look for life, it's not necessarily intelligent life; it could be bacteria or mold or a form people can't even imagine.

Before Wednesday, and the announcement of Kepler's findings, the count of planets outside the solar system stood at 519. That means Kepler could triple the number of known planets.

Kepler also found that there are many more relatively small planets, and more stars with more than one planet circling them -- all hopeful signs in the search for life.

"We're seeing a lot of planets and that bodes well. We're seeing a lot of diversity," said Kepler co-investigator Jack Lissauer, an astronomer at the University of California Santa Cruz.

All the stars Kepler looks at are in our Milky Way galaxy, but they are so far away that traveling there is not a realistic option. In some cases it would take many millions of years with current technology.

What gets astronomers excited is that the more planets there are -- especially those in the habitable zone -- the greater the odds that life exists elsewhere in the universe.

Yale University astronomer Debra Fischer, who wasn't part of the Kepler team but serves as an outside expert for NASA, said the new information "gives us a much firmer footing" to hope for worlds that could harbor life. "I feel different today, knowing these new Kepler results, than I did a week ago," Fischer said.

Shares