The Orange County district attorney has brought highly unusual misdemeanor charges against 11 Muslim students for disrupting a speech by the Israeli ambassador to the U.S. at the University of California at Irvine last year, raising questions about the First Amendment and the criminalization of protest on campus.

The case has generated competing free speech claims, with both sides arguing they have the Constitution on their side. Supporters of the so-called Irvine 11, including progressive Jewish groups, have argued that the prosecution is politically motivated because of the explosive nature of the Israel-Palestine issue and because the students are Muslim.

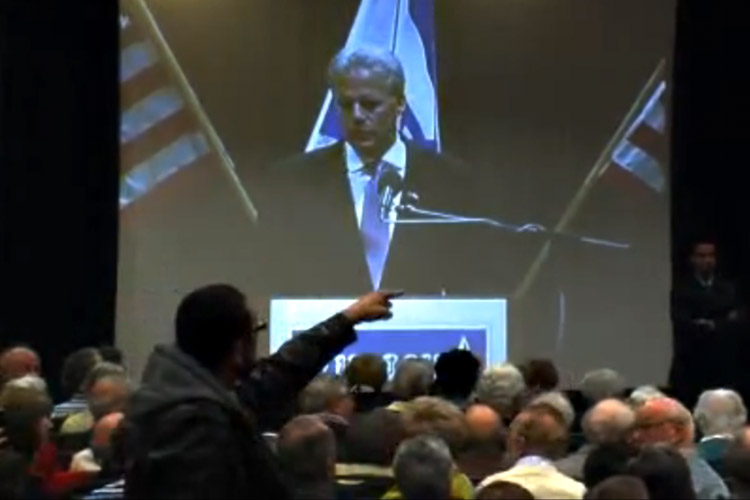

Ambassador Michael Oren came to speak last February at U.C. Irvine, which has been the site of tensions over Israel-Palestine for several years. Members of the Muslim Student Union took turns interrupting the speech every few minutes, calling Oren, who is an Israeli Defense Forces veteran, “an accomplice to genocide” and a “mass murderer.” Each student briefly stood up, shouting a sentence or two, then walked to the aisle and was arrested by police and escorted out. After four interruptions, Oren took a 20-minute break, according to news reports at the time. He was then interrupted another six times before a group of protesters left the lecture hall. Oren then finished his speech.

In response to the incident, the U.C. Irvine administration revoked the charter of the Muslim Student Union for a year and disciplined the students involved.

Now, after a year-long investigation that included issuing search warrants and convening a grand jury to interview witnesses, Orange County District Attorney Tony Rackauckas has brought charges against 11 students for “conspiring and disrupting a lawful assembly.”

Rackauckas, the longtime Republican D.A. in deeply conservative Orange County, has presented himself as a defender of the Constitution in the case. “These defendants meant to stop this speech and stop anyone else from hearing his ideas, and they did so by disrupting a lawful meeting,” he said in a statement. “This is a clear violation of the law and failing to bring charges against this conduct would amount to a failure to uphold the Constitution.”

But critics of the criminal charges beg to differ.

“If what the Orange County D.A. is doing here is allowed to proceed, then anyone who interrupts a speaker would be guilty of a crime under the California penal code,” says Daniel Mayfield, a San Jose criminal defense attorney who has represented many political protesters. ”It would be different if the students had come in and set off a stink bomb or come in and grabbed the microphones and started haranguing the audience. But none of that happened,” Mayfield adds.

Carol Sobel, a Los Angeles-based attorney and executive vice president of the progressive National Lawyers Guild, has been assisting the Irvine 11. “These students stood up momentarily, read a statement, went to the aisle, and the police escorted them out,” Sobel says. ”Our contention here is that there was no substantial disruption. Oren was able to complete his speech.”

Whether there was a substantial disruption is likely to be a crucial issue in the case; the phrase comes from Section 403 of the state penal code, under which the Irvine 11 have been charged. That law makes it illegal to disrupt certain kinds of meetings.

There’s also a California Supreme Court precedent that may come into play, the 1970 Kay case. According to Mayfield, the court held in Kay that, ”if you’re having a political meeting and there is a political purpose for it, then you have to accept non-violent disruptive behavior.” The Kay case centered on protesters who were calling for a boycott of non-union grapes, disrupting a speech by a congressman at a public July 4 event. They were arrested and charged under Section 403 of the penal code. A 6-1 majority of the state Supreme Court threw out the conviction, arguing in part:

Audience activities, such as heckling, interrupting, harsh questioning, and booing, even though they may be impolite and discourteous, can nonetheless advance the goals of the First Amendment

So another key question in the Irvine case may be whether Oren’s speech was a political meeting.

But there’s also the issue of selective prosecution. Public lectures on college campuses are disrupted by protesters all the time. How did the Irvine episode rise to the level of a prosecutable offense? I put that question to Susan Kang Schroeder, chief of staff for the Orange County D.A.

“Rarely do we get a case where the crime is on videotape,” she says. “We didn’t go looking for this. It came to us from U.C. campus police with a request to file a case. If [critics] don’t like the law, they can take it up with the California Legislature.”

I asked Schroeder what standard the D.A. would use in cases of other hecklers at campus events.

“It’s not an interruption of the speech, they have to stop the meeting,” she says, but then added: ”It has to rise to a point where it resulted in interruption of the speech.”

So it’s still not entirely clear what standard is being applied.

Sobel, the attorney working with the students, worries that the Irvine case could set a dangerous precedent. ”If the law is construed to mean any disruption, it would have sweeping effects,” she says.