This morning brings news that Haley Barbour, Mississippi's second-term governor and a former Republican national chairman, will be feted at a lavish D.C. fundraiser in a few weeks, with organizers each pledging to raise at least $10,000 for his PAC -- the clearest signal yet that Barbour is preparing to run for president. He'll also address the Conservative Political Action Conference on Saturday, further proof that he's looking to go.

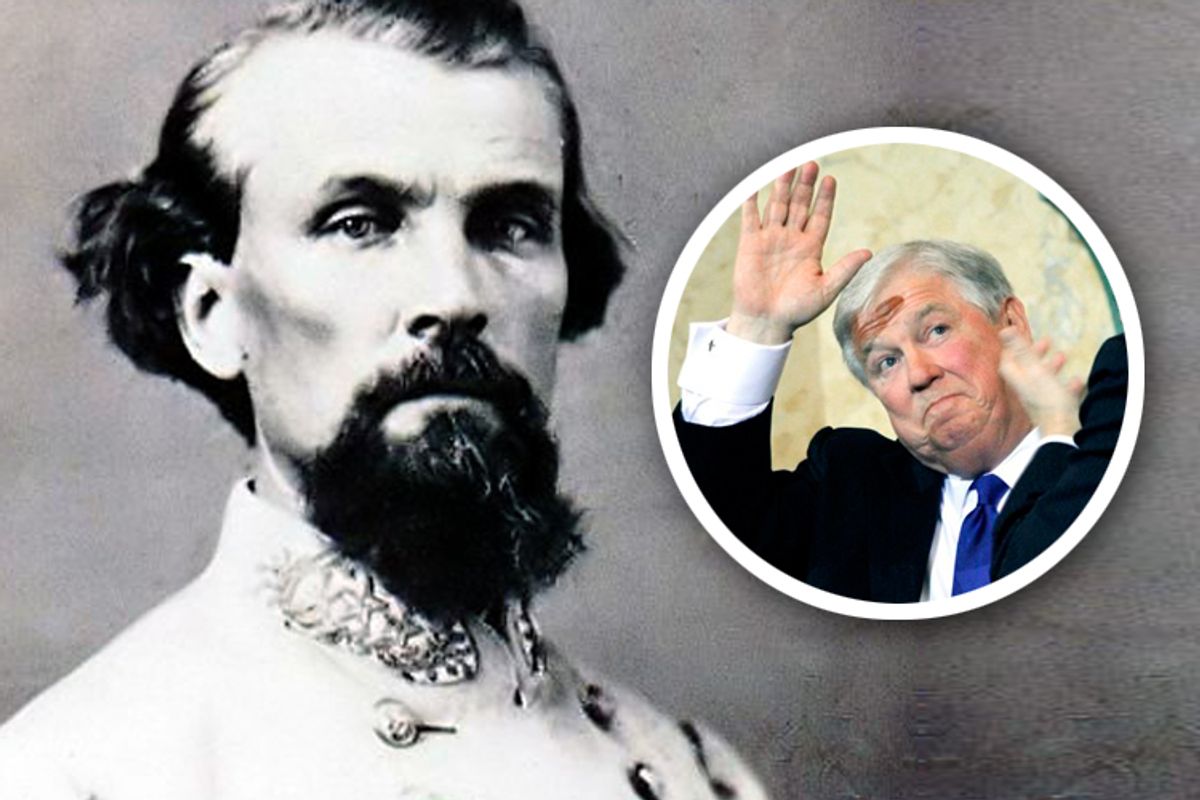

Meanwhile, back in the Magnolia State, the Sons of Confederate Veterans are mounting a campaign to issue commemorative state license plates in honor of the 150th anniversary of what the group still calls "the war between the states." One of the proposed plates would feature Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate general who served as the Ku Klux Klan's first Grand Wizard -- and who oversaw the infamous "Fort Pillow Massacre" of 1864. True, Barbour may end up ducking this one; the plan still has to be presented to the Legislature and passed. But it could land on his desk, too; the name Nathan Bedford Forrest still has resonance with many white Southerners.

That both of these stories emerged at the same time is fitting, since Barbour seems more haunted by the ghosts of Dixie than any major presidential prospect in recent memory.

It was, after all, just two months ago that Barbour fondly recalled the segregated Mississippi of his early-1960s teenage years as a warm, peaceful place. "I just don't remember it as being that bad," he said. Months before that, Barbour used an interview to claim that it was his generation of young Republicans that had pushed the South away from segregation and its Democratic proponents -- a highly misleading suggestion. He also spoke of forming a close friendship with one of the first black students admitted to the University of Mississippi, which he attended in the mid-'60s. That student, now a grown woman named Verna Bailey, said she didn't even remember meeting him. When he first ran for the Senate, a doomed campaign against John Stennis back in 1982, Barbour, in the presence of a New York Times reporter, chided a campaign aide who had spoken derisively of "coons" by telling the aide that he "would be reincarnated as a watermelon and placed at the mercy of blacks." Oh, and he keeps a Confederate flag signed by Jefferson Davis in his State House office in Jackson.

All of this may or may not hurt Barbour in a race for the GOP nomination. The party, after all, is dominated by conservatives and its power center is in the South. On a personal level, Barbour's racial history isn't likely to bother the average Republican nearly as much as it bothers the average non-Republican. But as a practical matter, it does seem possible that Republicans will bypass Barbour in '12 for fear of the negative impact his Dixie baggage could have in a general election campaign against America's first black president.

In this sense, Barbour may ultimately prove to be a transitional figure in the evolution of Southern conservatism. Unlike the generation of conservative Southern politicians before him, who were almost all ardent segregationists, Barbour entered politics in the post-civil rights era. He has no personal track record of joining filibusters, blocking schoolhouse doors, or engaging in the blunt race-baiting that was critical to Southern political advancement in the mid-20th century. Thus, he hasn't faced the same ceiling that stymied, say, Richard Russell, the Georgia senator who coveted the presidency but knew it was unattainable, thanks to his role as Jim Crow's preservationist-in-chief.

But Barbour still has plenty of Old South in him, and it tends to show when he talks about his own political roots and the Mississippi of his youth. To call Barbour racist is probably too much; the problem is more that he still seems to accept the version of Southern history that he and every other white child in Yazoo City was presented with back in the 1950s and early 1960s. He never really appreciated just what Jim Crow meant to the blacks who lived on the other side of town. He never really figured out how to talk about race outside of the South, other than to say he didn't like segregation.

Barbour is representative of the long-term result of the GOP's decision to nominate Barry Goldwater in 1964. White Southern conservatives, who had been loyal to the Democratic Party for their whole lives, began defecting to the Republicans in droves. Younger white Southerners, like Barbour, simply joined the GOP, and never looked back. In the five decades since, these white Southerners have still never seen one of their own make it onto a national Republican ticket; the closest they came was George W. Bush, technically a native Texan, but really a son of the New England aristocracy. Barbour may still be too "Old South" to make it to the White House, but the next generation of Southerners seems more capable of nuancing the region's racial history. Mike Huckabee, a baby boomer, is a good example. There are others. Here's guessing it won't be Haley, but sometime soon, an authentically Southern conservative will lead the GOP in a national election.

Shares