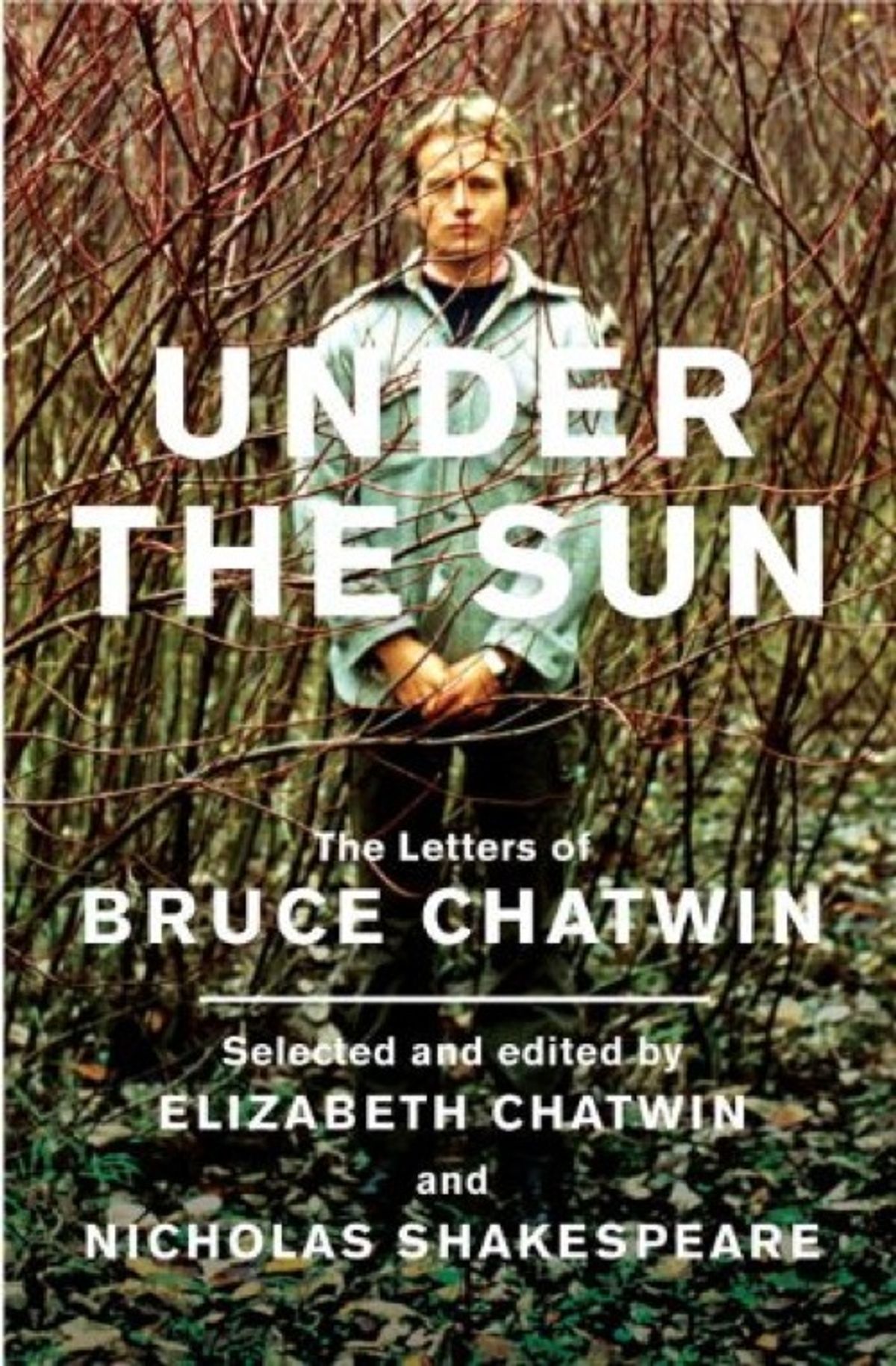

Bruce Chatwin, who died in 1989 before the Internet swept away all other forms of written communication, was probably one of the last great letter-writers. And being, also, one of the most peripatetic human beings in history, he had no choice but to write a lot of letters. Read in its entirety, his correspondence proves something that even Nicholas Shakespeare's wonderful 1999 biography didn't quite get across: that while Chatwin may have been egocentric, a self-mythologizer, and a professional seducer, the high excitement he manifested for the world around him was absolutely genuine. Nearly every missive in "Under the Sun: The Letters of Bruce Chatwin" (edited by Shakespeare with Elizabeth Chatwin, the author's widow) buzzes with it. One of his correspondents, the American author David Mason, put it well: "Some writers become self-advertisers out of a grating neediness. What I sensed from Bruce was more akin to uncontainable enthusiasm."

It was an enthusiasm that was manifest even in early childhood. Not everyone recognized it; one contemporary has stated flatly that "If you were to say, 'This is the boy who is going to be Bruce Chatwin,' I would have said: 'No, I don't think so.'" Perhaps not; but Chatwin's fascination with travel and adventure are evident even in the first pages of the collection, in letters written home from boarding school when the author was 8 years old. The books he asked his parents to send him at that time were "Swallows and Amazons," "The Open Road" and a book about gypsies "called Out With Romany by Medow [sic] and Stream.'" "Please don't send me any comics when I am ill," he instructed them, "they bore me. A boy's magazine such as 'Boy's Own' would be much more appreciated."

It was an enthusiasm that was manifest even in early childhood. Not everyone recognized it; one contemporary has stated flatly that "If you were to say, 'This is the boy who is going to be Bruce Chatwin,' I would have said: 'No, I don't think so.'" Perhaps not; but Chatwin's fascination with travel and adventure are evident even in the first pages of the collection, in letters written home from boarding school when the author was 8 years old. The books he asked his parents to send him at that time were "Swallows and Amazons," "The Open Road" and a book about gypsies "called Out With Romany by Medow [sic] and Stream.'" "Please don't send me any comics when I am ill," he instructed them, "they bore me. A boy's magazine such as 'Boy's Own' would be much more appreciated."

The theme of Chatwin's entire life, as he was the first to admit, was movement. "The question of questions: the nature of human restlessness," he commented, and copied into his notebook a pertinent aphorism of Montaigne: "I ordinarily reply to those who ask me the reason for my travels, that I know well what I am fleeing from, but not what I am looking for." What was Chatwin fleeing? The easy answer, one that a number of commentators on his life and work have opted for, is standard pop psychology: himself. He must have been a self-hating homosexual. His refusal, in the last years of his life, to acknowledge that he had AIDS reinforced this standard analysis. But thousands of people in the same position did not compulsively take to the road, and in the end it is probably futile to attempt to analyze what must have been a congenital restlessness. "Change," he wrote, "is the only thing worth living for."

That hunger for change, and an enormous aesthetic and intellectual avidity, led Chatwin away from the more conventional career paths. His first ambition was to go on the stage but his father, a lawyer, wouldn't allow him to go to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. He soon developed a passionate interest in French furniture. A position at Sotheby's was an option acceptable to both father and son, and Bruce went to work for the auction house while still in his teens, starting as a numbering porter in the Works of Art Department at £6 a week. He rose very rapidly in the firm: By the time he left, at the age of 26, he was head of Impressionist and modern art and one of the company's youngest directors. But the art business had come to disgust him. Later he would remember with a shudder "the nervous anxiety of the bidder's face as he or she waits to see if she can afford to take some desirable thing home to play with. Like old men in nightclubs deciding whether they can really afford to pay that much for a whore." In any case, Chatwin's deep distaste for institutional rules and regulations was already evident. It is probably what put an end, too, to his next professional venture, the attempt to qualify as an archaeologist. He quit the four-year course at the University of Edinburgh halfway through because, as he claimed, he didn't like disturbing the dead -- an unlikely rationale, considering the interest he took in the subject throughout his life. The truth is probably that academic protocol was simply too constraining.

But what he took away with him from Sotheby's and Edinburgh inspired and enriched his travels, and by the time he was 30 he had attained a level of erudition almost impossible to credit. His letters are full of this sort of commentary:

Some of that later Seljuk architecture can be appalling. Never cared one bit for that elaborate portal at Sivas, but have never been to Divrigi or Malatya. I don't quite agree with you over Hittite art. I think that Yazilikiya is most remarkable. It's very tough and solid, and requires a bouleversement of all one's ideas as to what is beautiful. I like it all the same in the time of the Old and early New Kingdoms. You're not, I suppose, going to Nimrud Dagh.

Chatwin had not originally considered putting his restless intelligence and numberless interests at the service of a literary career, but a gig curating a show of nomadic art of the Asian steppes brought him in touch with what was to be his great subject, and he began a long struggle -- Sisyphean, according to Elizabeth Chatwin -- with a book on nomads and the nomadic instinct. In the end he was defeated by the vastness of the subject and his own inexperience, and after three years he was stuck with an unpublishable manuscript. (He did complete an article for Vogue, which the editors, to his humiliation, titled "It's a Nomad Nomad Nomad NOMAD World.") The project would unexpectedly reach fruition 20 years later when Chatwin returned to the theme with "The Songlines," a wildly successful book that turned the author from cult favorite to bestseller. But his early letters to his publisher and others give us fascinating insights into his thinking on the subject.

One of the most exciting things this collection offers is the chance to glimpse the raw materials that went into favorites like "The Songlines,""In Patagonia," "On the Black Hill" and "The Viceroy of Ouidah." The baroque aspect of Chatwin's personality did not spill into his economical prose, and his ability to set a scene with a few well-chosen words is as evident in his casual letters as it is in finished works. Here he is in Patagonia, writing a letter to his wife:

Writing this in the archetypal Patagonia scene, a boliche or roadman's hotel at a cross-roads of insignificant importance with roads leading all directions apparently to nowhere. A long mint green bar with blue green walls and a picture of a glacier, the view from the window a line of Lombardy poplars tilted about 20 degrees from the wind and beyond the rolling gray pampas (the grass is bleached yellow but it has black roots, like a dyed blonde) with clouds rushing across it and a howling wind.

And here he is in Wales:

This morning it was blowing a gale, pouring with rain and the sun was shining strongly as well ... The sheep were the same golden color as the dying grass. A rainbow stretched from one corner to the other, and under it, a flock of rooks was blown this way and that, like black diamonds, glittering.

Chatwin was always on the lookout for "this mythical beast 'the place to write in,'" and he fell on his feet more often than one would have thought possible. After arriving at disappointing digs in India, for instance, he happened to meet "an extremely pukkah gentleman, ex-zamindar type" who offered the Chatwins his country fort.

Absolutely secluded, on a lake, with an ageing mother in the zennana, a kitchen full of cooks with traditions going back to the 17th century -- and I might say, fabulous miniatures ... On the lake, spoonbills, cormorants, pochards, storks, three species of kingfisher ... A cool blue study overlooking the garden. A saloon with ancestral portraits. Bedroom giving out onto the terrace. Unbelievably beautiful girls who come with hot water, with real coffee, with papayas, with a mango milk-shake. In short, I'm really feeling quite contented.

Chatwin expected to be taken care of, and it is surprising how often people did take care of him. One of the more pleasing aspects of these letters is Elizabeth Chatwin's dry but affectionate commentary on her husband's grandiose statements and unreasonable demands. He was always giving her very precise instructions on what to do in his absence: procure, deliver or collect various objects (for instance, a sack containing "a number of highly precious possessions, including a dried chameleon and the eardrum of a lion"); redecorate or make repairs on house and garden. "I'd bring down that old reed mat from the bedroom again for the drawing room -- and I'd whitewash inside the fireplace," he wrote once. "If you get the chance in Bristol why not have the Mahdi's flag and the Moroccan (it is 16th cent) textile put behind glass -- they fit exactly." A not untypical telegram from him was this one, sent to Elizabeth from North Africa:

NO PHONE HOPELESS COME ALGIERS 9 OCT STOP BRING DESERT SHOES ONE DRESS AND NOT LESS THAN 250 POUNDS WILL REPAY WILL GO CENTRAL SAHARA BRUCE

One can only speculate on the nature of the Chatwins' marriage -- mysteriously, except for a three-year separation from 1980 to 1983, they stuck it out together for over 20 years. One thing that comes through clearly in these letters, though, is that they never stopped loving each other, on one level or another. When Chatwin developed full-blown AIDS after 1986, and experienced severe hypomania as the disease began to affect his brain, Elizabeth did everything she could to make what remained of his life tolerable. Her work on this collection is also a labor of love, as indeed is Shakespeare's meticulous scholarship. Readers of the biography will be familiar with much of it, but addicts will want it all.

Shares