The newest numbers are significant, but hardly surprising: Nearly 60 percent of Americans now say they don’t like the Medicare overhaul plan that nearly every congressional Republican — and not a single Democrat — has lined up behind, while barely a third say they favor it. The findings, from a CNN poll released on Wednesday, mesh with other recent surveys and with a long accepted truism — that Americans (and senior citizens in particular) really, really like Medicare and really, really don’t like politicians messing with it.

But congressional Republicans have no choice but to mess with it (or to look like they’re trying to mess with it) because their political base, restive Tea Party activists and sympathizers, is demanding it — and that base proved in 2010 that it is willing to prioritize ideological purity over incumbency, establishment support and electability when picking candidates in primaries. Thus, congressional Republican leaders felt compelled to support and force their members to vote on Rep. Paul Ryan’s budget blueprint (which would turn Medicare into a voucher program), and only four Republican House members voted against it — even though the leadership and many rank-and-file members knew there could be severe general election consequences in 2012. This is how scared Republican elected officials are of their own base in 2011.

This raises a question: Why is the GOP base so insistent on forcing its elected officials to take positions that could endanger Republican control of the House? The answer to this tells us a lot about the evolution of the Republican Party over the last 15 years — and the stories and myths that political parties tell themselves in the wake of election defeats.

The best place to start the story is on Nov. 8, 1994, when Republicans scored one of the most sweeping midterm triumphs of the 20th century, grabbing control of the Senate for the first time in eight years and the House for the first time in 40 years. To the press and political observers, who had long ago begun placing the words “permanent Democratic” before “Congress,” it was a shocking development. To the victorious Republicans, it was proof that Americans had bought into an agenda as ambitious as it was conservative.

These Republicans had spent the last two years railing against Bill Clinton and his tax hikes, push for “socialized medicine,” and all-around liberal agenda. His victory in 1992, they told themselves, had been the product of two things: 1) the presence of third-party “spoiler” Ross Perot, who in their (inaccurate) telling disproportionately cost George H.W. Bush and boosted Bill Clinton; and 2) Bush’s abandonment of his 1988 “No new taxes!” pledge, which in their (also inaccurate) telling, plunged the country into the recession that hurt Bush so dearly in ’92. In other words, it was ideological betrayal and the presence of a nuisance candidate that cost them the White House, nothing else. No introspection needed here.

The trajectory of Clinton’s first two years in office only bolstered this sentiment. A series of blunders, missteps and mini-scandals sent his approval ratings plummeting early in his term, and the GOP’s staunch resistance to virtually his entire agenda — complete with over-the-top alarmism about creeping socialism, double-dip recessions and massive job losses — kept it low through 1994. Thus, when Republicans scored their midterm landslide, they took it as an affirmation of their interpretation of the ’92 election and a declaration of ideological solidarity from the public. Americans, they told themselves, had finally returned to their senses.

This is the attitude that compelled the GOP’s new House speaker, Newt Gingrich, and his fellow conservative revolutionaries to force a budget confrontation with Clinton in the fall of 1995. The Republicans demanded that Clinton accept their seven-year balanced budget plan, complete with a $270 billion cut in Medicare spending. They figured he’d fold, and if he didn’t, he’d surely pay a steep price. That was the message from 1994, right?

It wasn’t, of course, and when Clinton called the GOP’s bluff and slammed the GOP’s cuts as extreme and irresponsible, the public sided with him. What’s more, he and his fellow Democrats refused to let the Medicare issue go, making it one of the central issues of their 1996 campaign effort. Virtually every Republican congressional candidate in 1996 — incumbents and first-time candidates alike — was linked to the “Dole-Gingrich” plan to slash Medicare. Clinton ended up coasting to reelection, and while Republicans ended up holding on to Congress, nearly 20 GOP House incumbents ended up losing their seats.

To true believers on the right, it was baffling: All of the GOP rhetoric about government being too big and spending being out of control had polled so well in 1993 and 1994 — and yet when they tried to do something about it, the public resisted. They played the victim card, crying that Clinton and the Democrats had scared voters with misinformation and demagoguery. This made the party base feel better: Don’t worry, it wasn’t because voters disagree with us — they just didn’t know any better. But at the top of the party, others took note: Touching Medicare was poison.

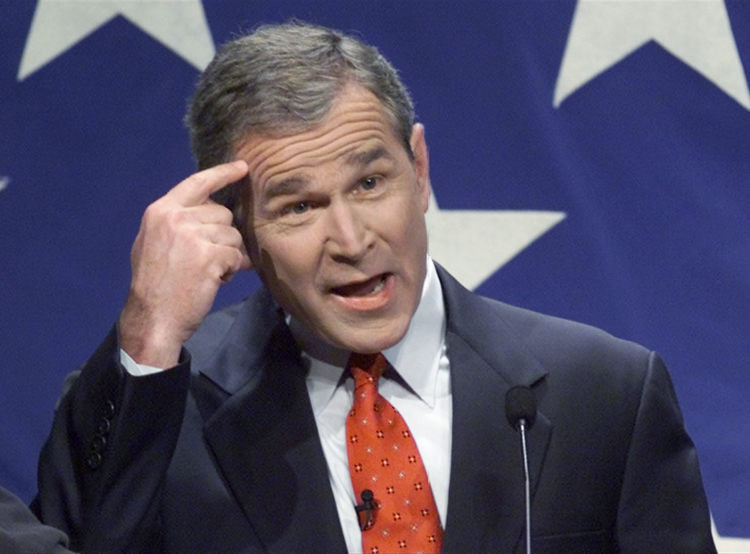

This is where George W. Bush comes in. After the 1998 elections — when Republicans again lost ground on Capitol Hill, this time because of their ill-advised drive to impeach Clinton — the GOP turned its focus to winning back the White House. Initially, the race looked wide open — no obvious “next in line” candidate for the first time in the modern era. But Bush, who had just won reelection as governor of Texas, quickly emerged as the consensus choice of party elites — elected officials (particularly his fellow governors), big-money donors and bundlers, and key coalition group leaders. The promise of Bush was simple: He had built-in credibility with the party’s base, but because of his name and his friendly manner, he also had the potential to win over the general election swing voters who had been so crucial to Clinton’s success.

And he had something else: “compassionate conservatism.” Bush’s strategy reflected an understanding of what had gone wrong since 1994, with Republican leaders turning off the general public with extreme-seeming efforts to dismantle government and attack Clinton personally. With compassionate conservatism, Bush would win those voters back by assuring them that he wouldn’t touch the Medicare third rail and wasn’t much interested in dismantling the government.

He delivered this message clearly in the fall of 1999, when he accused congressional Republicans — who were pushing an $800 billion tax cut bill and seeking to delay earned income tax credit payments — of trying “to balance their budget on the backs of the poor.” He then took a trip to New York, where he asserted that “of course we want growth and vigor in our economy, but there are human problems that persist in the shadow of affluence” and called for more federal education spending and more assistance for the poor.

“Too often, on social issues, my party has painted an image of America slouching toward Gomorrah,” he said. “Too often my party has confused the need (for) limited government with a disdain for government itself.”

While there was some grousing from conservative leaders, Bush received remarkable cover from the right for all of this. After eight years of Clinton, the GOP’s elites simply wanted to win again, and in Bush, they thought they had their own Clinton — a likable frontman who wouldn’t scare anyone away with extreme rhetoric or a polarizing personality. He was the anti-Newt and the anti-Dole.

Bush survived the GOP primaries, beating back a brief scare from John McCain, claimed the White House under circumstances we’re all familiar with, and then governed as a big government conservative. Taxes were cut, conservative judges were appointed, and lip service was paid to conservative causes, but there were no efforts to radically pare back the size and scope of government. In fact, government actually grew on Bush’s watch, mainly through his response to 9/11 but also thanks to the Medicare prescription drug benefit in 2003, perhaps the crowning achievement of compassionate conservatism. Spending went up, deficits soared and … Bush’s popularity with his own party never really waned. This was partly a reflection of the GOP base’s sense of loyalty to a “wartime president” from its own party, but it also demonstrated that most Republicans are perfectly willing to live with big government, provided that their party controls it. A similar lesson can be found in the presidency of Ronald Reagan, who also oversaw an expansion of the federal government (and a massive jump in the national debt) while paying lip service to conservative principles.

But then came the election of 2008, when the GOP – bogged down by a cratering economy, unresolved wars that Bush had started, and the country’s broad distaste for its president and the party that had enabled him — handed the White House to a Democrat and equipped him with massive House and Senate majorities. Republicans needed a way to explain this massive repudiation (which had actually started in 2006, when they’d lost Congress), and blaming their core philosophy was not an option. So they went with the same basic story they told themselves after the 1992 election: We let our leaders sell our principles out. Bush and Republicans in Congress, conservative thought leaders told their audiences, had compromised too much and, as a result, enacted liberal-ish policies that had wrecked the country. Only by returning to pure, absolute conservatism could their party — and their country — be made whole again. Compassionate conservatism had been their salvation a decade earlier, but now Republicans told themselves it was the worst thing that had ever happened to them. It had given them Barack Obama.

This is the mood that has defined the Republican Party since the election of 2008. It gave rise to the Tea Party movement — which is really just another name for the GOP’s base — and fueled conservative activists with a desire to rid their party of leaders who had collaborated with Democrats. It is the reason that fringe candidates like Sharron Angle, Christine O’Donnell, Joe Miller and Ken Buck were able to win high-profile Republican primaries in 2010, and the reason that a sitting U.S. senator — Bob Bennett — lost his party’s nomination at the Utah state GOP convention. And it’s the reason why, when his party took control of the House this past January, Speaker John Boehner decided that it actually made sense to touch the Medicare third rail once again — even if, this time, he and his fellow leaders were well aware of the general election risks. And it’s the reason why virtually every Republican in the House went along with him.