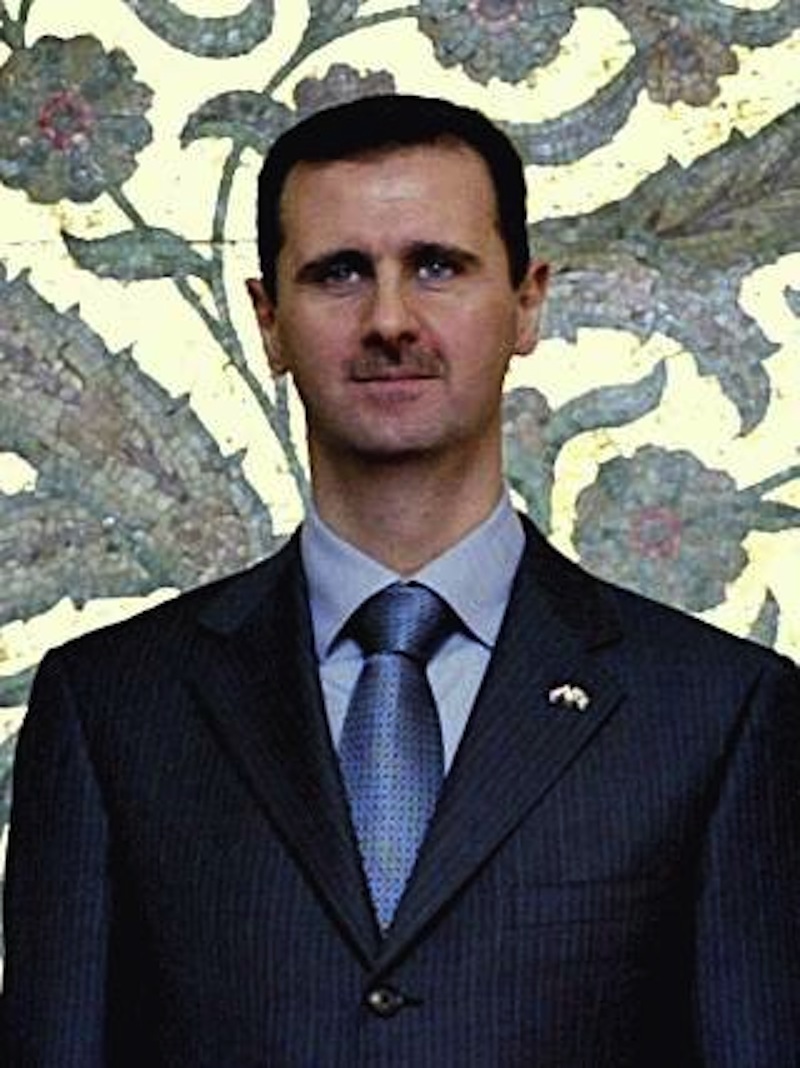

Syrian president Bashar al-Assad addressed the nation Monday for the first time in two months — and for the third time since the Syrian revolts began. Speaking from Damascus University, Assad hinted at the possibility of electoral reform, including allowing for other political parties alongside his ruling Ba’ath Party and opening up a “national dialogue.” The president’s pledge of minimal concessions, which were interspersed with condemnations of some of Syria’s protestors as “saboteurs”, will do little to satisfy his critics.

What did he say? Al-Jazeera aptly points out that Assad’s speech delivered “mixed messages.” He promised political reform but said no such reform was possible until protestors stopped carrying arms and enacting violence; he said that he would bring together an authority of 100 hundred people from various backgrounds to create a “national dialogue” (something promised in May that is yet to materialize); he said the state would not “exact revenge” on returning refugees; he distinguished between protesters he saw as legitimate and those he considered “saboteurs” and spoke too of “foreign conspiracies” as “germs.” He was vague on a timetable for change. Reuters details highlights of Assad’s speech here.

What was different about this speech? As the New York Times notes, this speech differed “in tone at least, from his first address after an uprising that erupted in mid-March, when he called the demonstrations a conspiracy fomented by foreign enemies.” Assad still spoke of foreign conspiracies, but noted the gravity of the situation in Syria, calling this a “defining moment.”

As the Arabist blog reports: The previous speeches were cocky and confident, arrogant even. In this one he seemed uncomfortable and nervous, gone was the joking and swagger of a month ago. He even appeared to have lost some weight.

What was not different? The content of Assad’s speech — his promises of reform — have, on the whole, been pledged before. On Monday he promised a general amnesty for members of political movement, including the Muslim Brotherhood, but in late May an amnesty was pledged and many political prisoners remain in jail; the same is likely to happen again given Assad’s reference to “saboteurs” as distinct from legitimate protesters. As mentioned above, his plan for a “national dialogue” is nothing new and was supposed to already be enacted. And Assad’s pledge to change Article 8 of Syria’s constitution to allow for more political parties than his Ba’ath Party was technically put into Syrian law in 2005.

The Guardian’s Martin Churlov tweeted that Assad still sounded like an “old-school overlord.” (Indeed, all his suggestions for reform are based on top-down governance: creating new committees under his leadership).

Response: The Guardian’s live blog on the Middle East reports that protestors have taken to the streets in response to Assad’s speech in the coastal city of Latakia and in the suburbs of Damascus, crying “no dialogue with murderers.” The Guardian blog shared this video of a response protest:

The international stance: British foreign secretary, William Hague, said Monday that Britain wanted Assad “to respond to legitimate grievances, to release prisoners of conscience, to open up access to Internet and freedom of the media.”

Meanwhile, Al-Jazeera reports, Ersat Hurmuzlu, an adviser to Abdullah Gul, the Turkish president, said that his government was willing to give Assad up to one week to implement reforms.

“The demands in this field will be for a positive response to these issues within a short period that does not exceed a week,” Hurmuzulu said.

Assad’s speech will likely not help settle the divide in international opinion on how to deal with Syria. Britain, France, Germany and Portugal are pushing for a U.N. Security Council resolution condemning the military crackdown, but Russia has indicated that it will block the move. In an interview with the Financial Times, Russian president Dmitry Medvedev said:

What I am not ready to support is a resolution [similar to the one] on Libya because it is my deep conviction that a good resolution has been turned into a piece of paper that is being used to provide cover for a meaningless military operation.

Assad’s speech Monday has done little to determine what happens next in Syria. According to human rights groups, 1,400 civilians have been killed in Syria while 10,000 have been detained in government crackdowns since the unrest began.