How do you get from establishing your pro-choice bona fides by solemnly invoking the pre-Roe v. Wade story of a "dear, close family relative who was very close to me who passed away from an illegal abortion" to adamantly demanding a return to the legal conditions that contributed to that relative's tragic death?

That's the leap that Mitt Romney made, and -- as Salon's Justin Elliott documented this week in a piece that told the story of Romney's relative for the first time -- he's never really squared the implications of his new position with the searing anecdote he told back in his first Massachusetts campaign, in 1994.

Some suspect Romney has always been pro-life, and that he only pretended to support abortion rights to get ahead in Massachusetts. Others wonder if he might still secretly be pro-choice, and only pretending to be pro-life to succeed in national GOP politics. But a close examination of his evolution on this issue suggests an even more cynical conclusion: that he doesn't believe anything at all. During his 17-year political career, Romney has actually changed his tune on abortion multiple times -- and always in a way that suited his political needs.

Here's the history:

1994: Romney, a largely unknown business executive from the Boston suburbs, seeks and wins the Republican nomination for the U.S. Senate in Massachusetts. There is a pro-life faction in the state GOP, but the party is publicly defined by a moderate-to-liberal sensibility on cultural issues. All three of its statewide elected officials -- Gov. Bill Weld, Lt. Gov. Paul Cellucci and state Treasurer Joe Malone (a recent convert) -- are pro-choice, as is one of the state's two GOP congressional representatives (Peter Torkildsen). This supposedly is the winning formula for a Republican in blue state Massachusetts, and Romney embraces it.

But his Mormonism and a primary season statement that he opposed federally funded abortions prompts some suspicion -- stoked by Democrats -- that he is not the strong supporter of abortion rights he claims to be. Romney counters this by shifting his position on public funding (embracing federally funded abortion for the victims of rape and incest and arguing that states should be free to pay for abortions for poor women) and by using his first televised debate with Kennedy to tell the story of his deceased relative, insisting that "you will not see me wavering on this":

After briefly leading Kennedy after the September primary, Romney loses the election by 17 points -- but abortion doesn't seem to be the reason. After the '94 race, he considers running for the Senate again in 1996, against Democrat John Kerry, but ultimately yields to Weld. In 1999, with no immediate political openings on the horizon in Massachusetts, he agrees to take over the troubled Organizing Committee for the 2002 Olympics in Salt Lake City.

2001: Romney is greeted warmly in Utah and wins rave reviews in the local press for his work -- stirring talk that he might stick around after the games and seek office in Utah. Specifically, talk centers around the governorship, which is expected to be open in 2004, when Republican Michael Leavitt's third term is due to expire.

In the middle of 2001, this seems like it may be Romney's best bet if he wants to win elected office. Back in Massachusetts, a Republican (Jane Swift) has just taken over as acting governor, and is expected to run with the party's backing for a full term in 2002. (There is some talk that Romney might challenge her, but he publicly shrugs it off.) And Kennedy and Kerry are safely locked into their Senate seats. But to have any chance in Utah, Romney will have to change his abortion position. The state is far, far more conservative than Massachusetts and the Utah GOP uses a convention dominated by the far right to hand out its nominations. This is the context in which Romney pens a letter to the editor of the Salt Lake Tribune in the summer of 2001, disputing the paper's characterization of him as a supporter of abortion rights. "I do not wish to be labeled pro-choice," the letter reads. The statement seems intentionally cryptic -- allowing Romney to potentially remake himself as a full-fledged pro-lifer if he decides to run in Utah, but still leaving enough wiggle room to return to Massachusetts as an abortion rights supporter if he so desires.

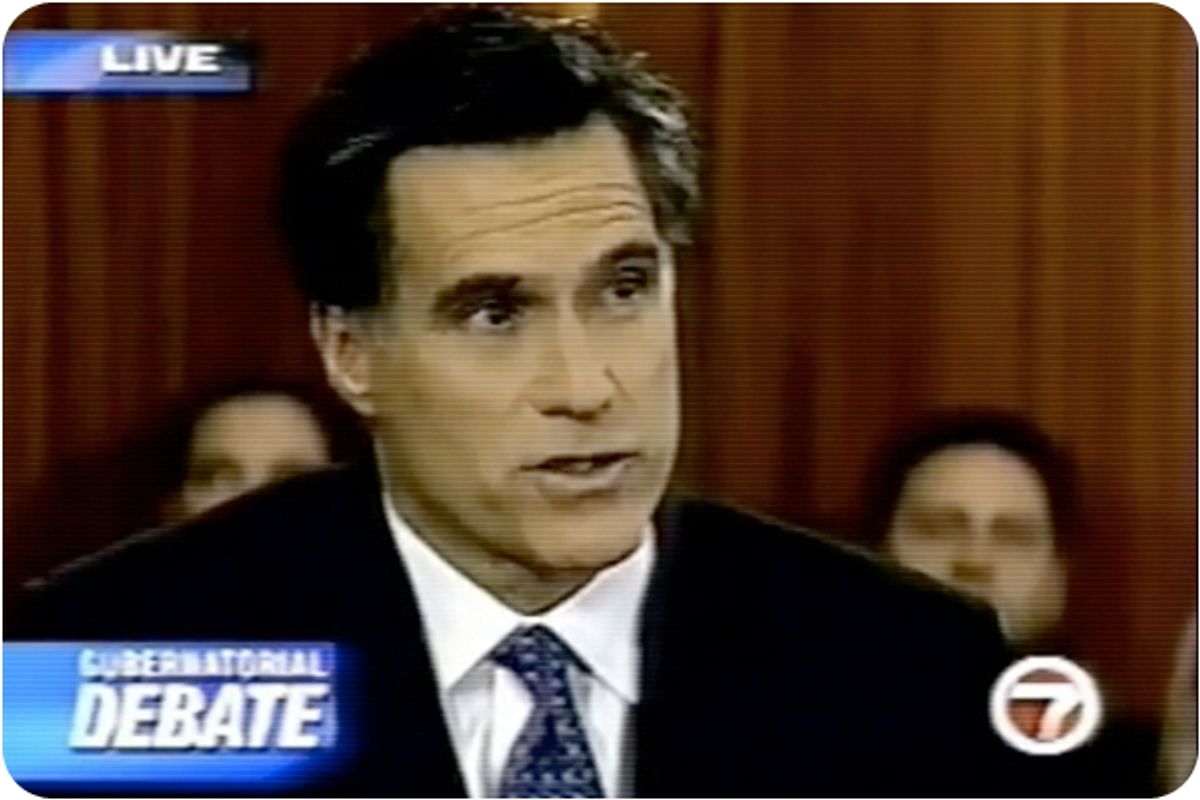

2002: When the Olympics end, Romney is hailed as a national hero. At the same time, Swift's poll numbers in Massachusetts collapse. Her governorship is a disaster and the state GOP quickly sets its sights on Romney as its savior. Romney obliges, letting party leaders and fundraisers muscle Swift out of the way, then returning to Massachusetts in March and jumping in the gubernatorial race. Quizzed about his letter to the editor the previous summer, Romney plays dumb: Of course he supports abortion rights -- he just doesn't like labels!

But the context of this race is different from 1994. Now, thanks to his Olympic role, Romney has national aspirations. But this is tricky: Running as a pro-choicer is smart politics in Massachusetts, but it's suicide at the national GOP level. So this time around, Romney is far more delicate in how he addresses the subject. The death of his relative is not invoked. He talks more about the idea of respecting the state's abortion laws, and less about his own belief that those laws are just.

In an effort to flush him out, his Democratic opponent, Shannon O'Brien, moves to his left, arguing against parental consent laws. But in the campaign's pivotal debate, Romney skillfully turns the tables on her, insisting that he is just as committed as she is to protecting a woman's right to choose and claiming that the only difference is "with regard to 18-year-old -- or 16-year-old -- consent." During the same debate, Romney claims that in his '01 letter to the editor in Utah, he had said that "I don't accept either label -- pro-choice or pro-life." This is not true. The letter had only said that he rejected the pro-choice label. Moderator Tim Russert points this out, but Romney ignores him:

Romney satisfies the state's swing voters that he is not a closet conservative on cultural issues and wins the election by 7 points.

2004: Romney's efforts to rebuild the Massachusetts Republican Party blow up in his face, with the GOP -- already barely a factor on Beacon Hill -- actually losing seats in state legislative elections, despite a lavish campaign that Romney helped fund and organize. This comes just months after the state's Supreme Judicial Court declared gay marriage legal, a ruling that put the state in the national spotlight on an issue that conservatives care deeply about. As the year ends, Romney seems to choose between his state and national imperative, embracing conservative views he'd previously shied away from. In 2005, he vetoes a contraception bill and declares himself pro-life. That same year, he spends dozens of days out of the state laying the groundwork for a 2008 White House campaign, and -- with his in-state poll numbers dropping -- he announces at the end of '05 that he won't seek a second term the next year.

2006: Edging closer to a formal announcement of his presidential campaign, Romney trots out his abortion conversion story, claiming that he decided to become pro-life during a private meeting in late 2004 with a Harvard stem cell scientist, Douglas Melton. In Romney's story, he was horrified when Melton cavalierly told him, "Look, you don't have to think about this stem cell research as a moral issue, because we kill the embryos after 14 days."

If that sounds a little too tailor-made for Romney's new target audience -- the Ivy League-wary cultural conservatives who loom large in national GOP politics -- it may not be a coincidence: Melton emphatically denies ever saying such a thing to Romney. But it almost doesn't matter: Romney, it seems, has found a new compelling personal anecdote to replace his old one.

Shares