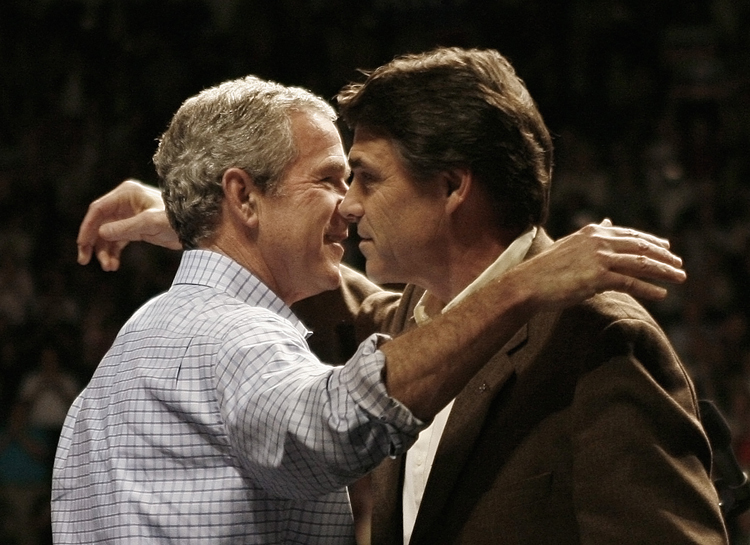

Rick Perry probably won’t admit it, but the man who, more than anyone else, is responsible for his current status as a top (the top?) Republican presidential candidate is George W. Bush.

The literal reason for this is well-known, and dates back to 1998, when Bush, then a shoo-in candidate for reelection as governor of Texas, provided critical support to Perry, who was locked in a tight down-ballot race for lieutenant governor. Perry’s narrow victory put him in line to succeed Bush two years later, and the rest is history.

But there’s a less direct reason for Perry to be grateful to his Austin predecessor. It has to do with the ultimate failure of the Bush presidency, which was instrumental in bringing about today’s radicalized Republican Party base — a transformation that Perry spotted early and that he has capitalized on brilliantly. The story of when and how Perry did this tells us plenty about him as a politician, but it also serves as a handy guide to the evolution of the 21st century Republican Party.

It begins back in 1999, when Bush entered the presidential race as the overwhelming favorite of GOP regulars and the conservative establishment. He shattered fundraising records, racked up countless endorsements, and surged to the front in national and key state polls. One by one, rival candidates quit the race in dejection — Lamar Alexander, Bob Smith, Pat Buchanan, Elizabeth Dole, Dan Quayle, John Kasich — leaving only John McCain in the way. And when McCain put a scare into Bush after winning the February 2000 New Hampshire primary, Bush’s network of supporters quickly and efficiently mobilized to marginalize the insurgent and save their guy. And that was that.

That Bush was able to create such startling unity within the party was partly testament to the power of his famous name and his rich friends. But it was mainly an expression of where the GOP was. After eight long years of Bill Clinton, Republicans were approaching the 2000 election with an Al Davis attitude: Just win, baby.

When Clinton was first elected, they’d treated him like a fluke president (Ross Perot was blamed, incorrectly), assumed he was a certain one-termer, and resisted his agenda bitterly. And when the 1994 midterms produced a historic GOP landslide, they marveled at how easy it had been to defeat him. They never imagined that he’d dust himself off and cruise to a second term in 1996. And even after that, they still thought they had him on the ropes when the Monica Lewinsky scandal broke. But Clinton only grew more popular during the impeachment saga of 1998, so much that Democrats actually gained seats in the fall’s midterms, an almost unheard of feat for the in-power party.

In other words, as Republicans turned their attention to the 2000 election, they were in an unusually pragmatic mood. They’d once believed that the ’94 midterms had been a popular endorsement of their government-slashing agenda, but when the GOP Congress actually tried to implement that agenda, Clinton portrayed them as heartless extremists, and voters rallied to his side. Republicans were sick and tired of losing like this, which is why Bush was so attractive to them: What better way to fight the Democrats’ social safety net demagoguery than with “compassionate conservatism” — Bush’s effort to convince swing voters that Republicans believed government could and should do good things too. He put it this way in his announcement speech:

Should our party be led by someone who boasts of a hard heart? I know Republicans across the country are generous of heart. I am confident the American people view compassion as a noble calling. The calling of a nation where the strong are just and the weak are valued. I am proud to be a compassionate conservative. I welcome the label. And on this ground I’ll take my stand.

Did this bother plenty of conservatives? Sure. But by 1999 and 2000, they’d grudgingly concluded that it was the only way they were going to finally start beating the Democrats again. So they got on board. Here’s how Rush Limbaugh, who played a crucial role in marginalizing McCain after New Hampshire, justified it:

Conservatism is easy to explain. It is compassion. George W. Bush runs around talking about compassionate conservatism, and he’s doing it because the liberals have so successfully demonized conservatism — it is racism, it is sexism, it is bigotry, it’s homophobia and all that. It’s not. The essence of compassion is conservatism.

Rick Perry was on board, too. When the Supreme Court settled the 2000 election in Bush’s favor, Perry was elevated to governor. “Certainly, you are not going to see a great philosophical difference between Rick Perry and George Bush,” he said. “We share the same type of philosophy.”

And for the first half of Bush’s presidency, Perry and most other Republicans stayed on board even as Bush implemented big government conservatism — a massively expanded federal role in public education (courtesy of a deal with Ted Kennedy and George Miller), a giant new prescription drug entitlement program, the creation of a brand new Cabinet department and so on. Every now and then, there’d be some grumbling on the right about Bush’s spending binge, but it didn’t amount to anything. Bush’s approval rating with Republicans remained astronomically high and he was reelected in 2004 thanks in large part to the party base’s devotion to him.

It was in his second term that everything changed. For the first time in his presidency, due mainly to news from Iraq that seemed to get grimmer each month and to his administration’s feeble response to Hurricane Katrina, Bush’s poll numbers began to plummet, first under 50 percent, then into the low 40s, and then into the 30s. His formula had stopped working, and when Republicans were blown out in the 2006 midterms (losing the House for the first time since 1994 and the Senate for the first time since 2001), the leaders and activists who had once acquiesced to the supposed necessity of compassionate conservatism began jumping ship. It was because Republicans had betrayed their own ideological principles, they decided, that the Bush presidency had failed and the GOP’s image was in disrepair. Or, as Limbaugh put it a few days after the ‘06 election:

The way I feel is this: I feel liberated, and I’m going to tell you as plainly as I can why. I no longer am going to have to carry the water for people who I don’t think deserve having their water carried.

It was in this climate that the Republican Party as we know it today and Rick Perry as we know him today were both born. The torment of Bill Clinton was now ancient history for Republicans, and many couldn’t remember why they’d felt the need to embrace compassionate conservatism in the first place. Whatever the reason, they were now adamant that only by embracing a pure, unbending form of conservatism could the GOP regain power — and keep it.

And Perry grasped this right away. All the way back in 2007, he began recasting himself as a fierce anti-government crusader, someone who was just as appalled at where the party had ended up as the average conservative activist. “We made an error with that phrase ‘compassion conservative,'” he said that December. At the same event, Perry allowed that Bush had been “better than Al Gore” but insisted that he “was never a fiscal conservative. I think people thought he was.”

The GOP’s yearning for purity only grew as Bush’s poll numbers plunged further in 2007 and 2008, and it reached new levels when Barack Obama racked up swept to victory with a bigger share of the vote than any Democrat had received since LBJ in 1964. They’d strayed from their principles and it had led to a socialist, anti-American president. Never again! The Tea Party movement, comprised mainly of functionally Republican conservatives who loathed Obama but believed the GOP had been complicit in his rise, mobilized to fight the new president.

And Perry was well on his way to being one of the new movement’s heroes. “We’ve got a great union,” he said at one of the first Tea Party rallies in early 2009. “There’s absolutely no reason to dissolve it. But if Washington continues to thumb their nose at the American people, who knows what might come of that?” Soon he was writing a states’ rights manifesto (2010’s “Fed up”), branding Social Security a “Ponzi scheme,” and accusing the chairman of the Federal Reserve of “almost treasonous” conduct.

This was not, mind you, what Perry sounded like a decade ago – probably because there was no reason to. The Republican Party was in a fundamentally different place back then. But as Bill Ratliff, who served as his lieutenant governor in Texas from 2000 to 2003, told the New York Times earlier this week, “I think he’s the best I’ve ever seen at picking up on a trend, a movement, and getting out in front of it very early.”

Perry’s surge to the front of the GOP pack this summer shows just how different his party is today than it was when Bush set out to run. The Republicans of 1999 had been schooled by Bill Clinton over and over again and were mainly hungry for a winner. But the Republicans of 2011 are coming off of a monster midterm triumph. They have yet to be humbled, and they want more than a winner. They want purity. And right now, Rick Perry is giving it to them.