In an attempt to blunt the surging presidential candidacy of Texas Gov. Rick Perry, Mitt Romney recently embraced two hot-button immigration issues in an appeal to Tea Party followers: He called for an end to so-called sanctuary cities harboring undocumented aliens, and he insisted that the next president “must do a better job of securing its borders, and as president, I will.”

Yet, Romney’s hard-line rhetoric overshadows a family secret: Few have benefited more from porous borders and “sanctuary” cities on either side of the border than the Romney family.

Last week, in fact, both Perry and Romney put in well-covered calls to Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio for advice on the immigration issue. In the 19th century, Arpaio would have been taking a close look at the Romney’s familial flouting of Arizona law.

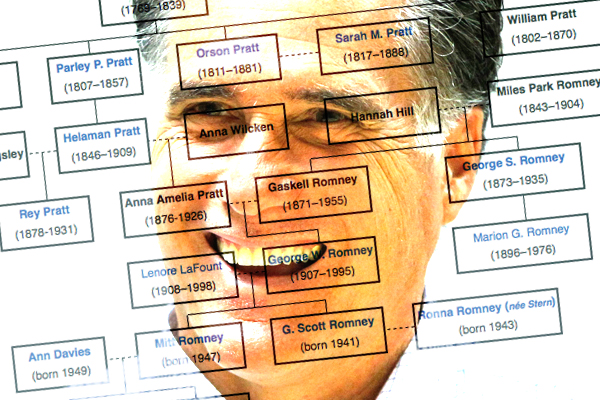

Romney’s ancestral legacy of polygamy, of course, is hardly news. The Washington Post did a feature story last month on Romney’s sizable family community in northern Mexico, and the role of his great-grandfather Miles Park Romney, “who came to the Chihuahua desert in 1885 seeking refuge from U.S. anti-polygamy laws.”

But the Post didn’t quite tell the full story. Nor do two chapters in Romney’s 2004 memoir, “Turnaround: Crisis, Leadership, and the Olympic Games.” In the book, Romney recounts his version of his great-grandfather’s removal to Mexico:

“… Miles Junior was asked to move again, this time to build a settlement in St. Johns, Arizona. To every request, Romneys were obedient. And leaving behind all that they had worked to establish, they yet again pitched themselves against the arid terrain, the cactus, the alkali, quicksand, and rattlesnakes. They built schools and libraries. Miles Junior was the founder of a theatrical society on the frontier. He dug irrigation ditches and plowed up the desert soil.

Eventually Miles was called upon to settle in northern Mexico, where his son, my grandfather Gaskell, would wed and my father George would be born …”

Romney concludes the story of his great-grandfather, who died in Mexico in 1904: “Despite emigrating, my great-grandfather never lost his love of country.”

In truth, while Romney’s great-grandfather may have never lost his love of the United States, he didn’t leave Arizona on good terms. Or even legal ones.

In the 1880s, the Mormons of Arizona didn’t just face increasing persecution for their polygamous ways. They also confronted resentment over their aggressive land deals and encroaching settlements. Five Mormons, including William Flake, (the great-great-grandfather of Republican Senate candidate and Rep. Jeff Flake of Arizona), were convicted of unlawful “cohabitation” in 1884 and sent to prison. In a related land claims dispute involving Miles P. Romney, Mormon leader David Udall (the great-grandfather of U.S. Sens. Tom Udall, D-N.M., and Mark Udall, D-Colo., was sent to prison in Detroit on perjury charges.

Miles Romney took a different course. Faced with the same perjury charges over his land claim in St. Johns, Ariz., in the spring of 1885, Miles Romney went on the lam and forfeited over $2,000 in bond, according to Dave Udall’s diary. A local newspaper account said Romney’s flight left his community “in the lurch,” and scholars agree.

“Fearing he would be prosecuted for polygamy, as well as for the earlier charge of perjury regarding his land claim, Romney skipped bond and fled to Mexico,” wrote Mormon historians JoAnn Blair and Richard Jensen in the Journal of the Southwest in 1977.

In other words, the candidates’ forefathers fled to Mexico for sanctuary, the very behavior that Romney is denouncing among Mexicans and others who come to the United States. Running for president in 2007 Romney called out New York, San Francisco and other cities for passing sanctuary policies.

“Sanctuary cities become magnets that encourage illegal immigration and undermine secure borders,” he declared.

In his memoir, Romney skims over his family’s lawless behavior and picks up the story from the border, seen through the eyes of one of Miles P. Romney’s “plural” wives:

“When she arrived at the border of Mexico, she was asked to pay an entry toll. Having no money, she was forced to leave behind the iron stove that she had carried across the wilderness as collateral.

Theirs was a life of toil and sacrifice, of course, of complete devotion to a cause. They were persecuted for their religious beliefs but they went forward undaunted.”

Two decade later, Romney’s ancestors returned. Having sided with Mexican dictator Porfirio Diaz, the Romney clan fled their homes and ranches in 1912 when the Mexican Revolution came to town. Along with thousands of Mormons they took advantage of the porous borders to find refuge in sanctuary cities, such as in Texas, Ohio, New Mexico and Arizona. They also received more than $20,000 allocated by the U.S. government for aid and relocation efforts.

“He had an abiding loyalty to America,” Romney concludes, “and a deep interest in politics. These were the same values and commitments that animated my grandfather and my father and my mother. They were the same values that were passed along to me.”

Now his values include supporting Arizona’s SB 1070, which seeks to supersede federal immigration law by making it a crime to be in the state without proper residency documents and requiring police to verify immigration status in a case of reasonable suspicion. With key provisions of the law struck down twice by federal courts, Gov. Jan Brewer recently filed an appeal before the U.S. Supreme Court.

In the spring of 2010, Romney was the first Republican contender to speak in support of SB 1070, which would punish immigrants from Mexico for doing what his ancestors did. The former Massachusetts governor’s statement was guarded, yet unmistakably in favor of the state’s mandates on police enforcement of immigration status. Romney declared: “Arizona’s new immigration enforcement law is the direct result of Washington’s failure to secure the border and to protect the lives and liberties of our citizens.”

To be sure, he added, “It is my hope that the law will be implemented with care and caution, not to single out individuals based upon their ethnicity.”

In New Hampshire last week, Romney doubled down on his new hard-line position, even while contradicting his support for Arizona’s states’ rights push. “As you know, I opposed sanctuary cities as the governor of my state,” Romney said. “And the idea that a city would determine that it’s not going to follow the U.S. law is unacceptable and immigration law is federal law.”

Immigration law is federal law? As Romney challenges Perry on immigration he might want to keep that little nugget — like his family history — a secret in Arizona, as well.