Historically, some of the most biting, provocative and vigorous works of social commentary have been virtually wordless. Good caricatures are almost always visually arresting; when conceived as works of satire, they can also carry powerful political and philosophical messages. Over the centuries, creators and publishers of caricatures and satirical imagery have pushed various social and political envelopes in order to communicate their theories and perceptions about contemporary life.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new exhibition, “Infinite Jest,” traces the path of artistic caricature through the centuries, charting the evolution of style and subject matter over time — beginning with the late Renaissance, lingering in the tumultuous 18th and 19th centuries, and moving straight on into the present day, by way of mid-20th-century treasures such as Al Hirschfeld’s “Americans in Paris” (Slide 12 — keep an eye out for famous expats such as Wallis Simpson and Ernest Hemingway).

In an email interview, Nadine Orenstein, one of the show’s two curators, described the theme and aims of the exhibition, as well as some of the individual works featured therein. Click through our slide show to get a glimpse of some of the works currently on display.

Can you explain the choice of the exhibition’s title, “Infinite Jest”?

The title comes from a work in the exhibition, Justin Howard’s “Chicago Nominee” [Slide 10]. The print was made during the presidential election campaign that took place in 1864 during the Civil War. The quote “I knew him Horatio, A fellow of Infinite Jest … Where be your gibes now” comes from “Hamlet.” In the print, Gen. George McClellan is caricatured as Hamlet in the graveyard scene of Act 5 — and instead of a skull of the court jester Yorick, he is holding the head of President Abraham Lincoln, his opponent. The title refers to false reports that Lincoln had acted with inappropriate levity while touring the battlefield at Antietam. Beyond the reference to the print, “Infinite Jest” worked for us because, beyond its original context, it evokes the idea of the variety of works in the exhibition coming from many different periods. It hopefully also evokes one of the themes of the exhibition about the continuity of approaches to caricature over the centuries — the fact that these artists were well aware of what preceded them and built on their precedents.

What, in simple terms, is caricature? How does it change — in terms of style or social function — over the period charted by the exhibition?

Caricature is difficult to define. The term originally meant an exaggerated portrait drawing. The essence of the words “carico” and “caricare” in Italian can be translated respectively as “to load” and “to exaggerate.” The Carracci, who are credited with first using this term, applied it to pen drawings of distorted human heads. The French still call caricatures of people “portraits-charge,” meaning loaded portraits. By the late 18th century in Britain, the term had become a catchall for a range of images that did not necessarily contain recognizable likenesses. Many of the political prints in the exhibition are not images of a single person, but rather of situations, and these prints were called caricatures in their day. These days it can be applied to a variety of works depicting exaggerated faces, extreme physiques, fantastic forms composed of inanimate objects and even animals acting like humans. Pure caricature, as we think of it today, is really focused on exaggerating the features of a known person.

What is it about Leonardo da Vinci’s works that led you to start the exhibition with him? How were his images — or their reception — different from what had come before?

Leonardo did not create caricatures. His numerous drawings of odd physiognomical types were probably meant as just that — drawings of unusual faces possibly intended for a treatise of physiognomy. He was clearly fascinated by people with unusual heads and Vasari says that he followed people around in the street in order to memorize their features. These small drawings that he made were then copied in drawing by his favorite student, Melzi, and more importantly in prints by Wenzel Hollar and others; it is through these works that they became famous in later centuries. We include him in our exhibition because by the 18th century, these works were considered to be caricatures. [William] Hogarth, in his print “Characters and Caricaturas” of 1743, warns against caricature, which he saw as a debased foreign form — and he illustrates a Leonardo drawing as a form of caricature. We included Leonardo in the show as a precursor to caricature and to show the great interest in unusual physiognomy that was a precedent for caricaturists like [Thomas] Rowlandson and others who clearly were aware of such works.

Who consumed these works? Have consumer demographics changed a great deal over the course of the period charted here?

In the late 18th and early 19th century, caricatures were sold in print shops and displayed in the shop windows that would change every few weeks. The shops in London and Paris were famous, commented on in guidebooks of the time, and there crowds would gather discussing the latest ones. In a way, they served a function very much like “The Daily Show” or “Saturday Night Live” do today — political or social humor that is shared by a wide variety of public and discussed the next day. It was through these works that very pointed political commentary was made. In the early to mid-19th century in France, caricatures started to appear in journals and there were a number of popular journals that included at least one caricature per week that was accompanied by a printed explanation of the image. Daumier’s prints appeared in one of these, La Caricature, published by Charles Philippon in Paris. This was a high-end journal in which the prints were printed on good paper and they could be hung on walls. The same publisher also produced a lower-end journal, Le Charivari, with images produced on less good paper where the text showed through (these journals could be purchased at a smaller cost).

We should also talk about the question of censorship, because it was during periods of relatively little censorship that caricature flourished. That is one of the reasons that England has such a rich caricatural tradition; there was no censorship on these images. France, in contrast, went through periods of strong censorship followed by less censorship. Delacroix, better known as a romantic painter, got his start making caricatures for the journal Le Miroir, and among these are two that comment on press censors. Daumier’s prints that viciously attack King Louis-Philippe and his ministers were created at a time when there was less censorship, but the censors began to crack down more and more until the censorship laws imposed in 1835 made it impossible to create such works anymore. Thereafter, Daumier and the other caricaturists of La Caricature turned their efforts toward lighthearted social satire. The publisher Philippon created a series of prints called “L’Association Mensuelle” in order to raise money for his court costs and fines resulting from censorship. [Slide 9, “The Legislative Belly” — which mocks prominent French legislators by exaggerating their supposed individual and collective sloth — is an example of Daumier’s work.]

Why aren’t there more 20th/21st century works in the exhibition? Have modern caricatures and satirical cartoons — like those in the New Yorker, for instance — evolved into a new genre, with different techniques and philosophical preoccupations? Or did the choice have more to do with logistical constraints?

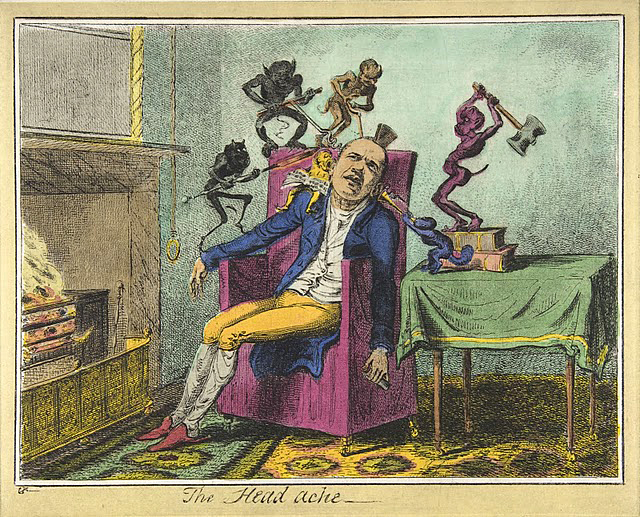

This exhibition was meant to highlight this little-known part of [the Met]’s collection, and the content was more or less dictated by what we had before us. Our strengths in this area really lie in the 18th and 19th centuries — and we certainly have enough of that material to fill many more additional exhibitions. We found some fabulous works in the collection that should be surprises even to people who know the field. We do have some drawings for New Yorker cartoons, but not that much, and we felt that cartoons were a very different kind of work and we also decided not to include comics. Both those forms get us into other very rich areas of artistic creation, which are not well represented in our collection. We also tried to focus on works that deal with exaggerating the human form in some way — building out on the purest meaning of caricature. Among the most recent works is a print by Enrique Chagoya [Slide 13], which he made for the big print festival in Philadelphia last year called Philagraphika. He adapted a 19th-century caricature by George Cruikshank called “The Head Ache,” which shows a man suffering from a headache with little monsters attacking his head. Chagoya (whose work often plays off works by earlier masters) substituted the man’s head with that of President Obama in order to create a commentary on his problems with the healthcare reform bill. I thought that it would be a great addition for the exhibition because it brings out one of our themes about artists being aware of their predecessors and building on their contributions.

[This interview was edited before publication.]

“Infinite Jest” is open at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York through March 4, 2012. A catalog of the exhibition has been published by Yale University Press.