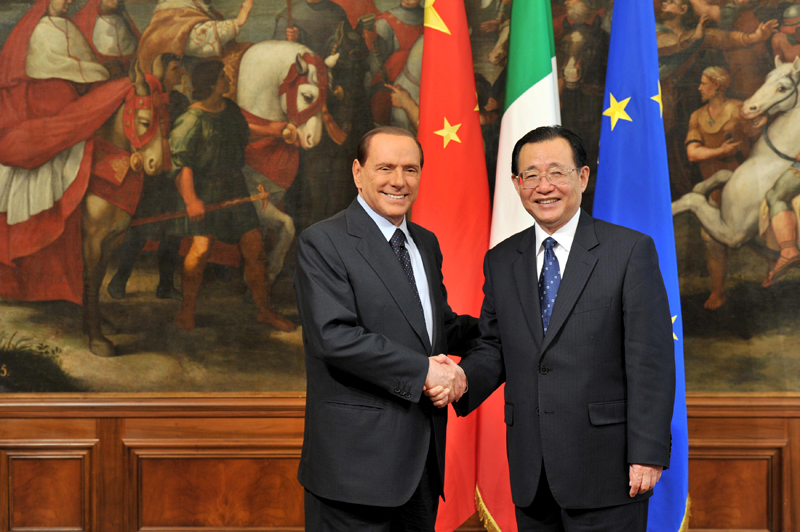

NEW YORK — In recent days, Italy became the first major Western economy to turn to China for what amounts to a bailout.

Italian officials confirmed last week that they held talks with China’s $340 billion sovereign wealth fund about buying Italian government bonds.

Italian officials confirmed last week that they held talks with China’s $340 billion sovereign wealth fund about buying Italian government bonds.

Little was written outside the financial press about this development. In Italy, where national debt now exceeds 120 percent of GDP, news that senior officials had set up a hotline to the cash-rich East was greeted as a sign of hope as the bond markets threaten to shut down the Italian government’s access to capital.

Italy, the eighth largest economy, is a founding member of the U.S.-led Group of Seven (G-7) club of industrial economies that until recently called the shots in the global economy. Not long ago, the idea that a global export and financial powerhouse like Italy would turn for assistance to China, the chief proponent of authoritarian state capitalism, would have raised alarm bells in the United States. America would have scrambled to engineer a rescue, as it did in Mexico in 1994, South Korea in 1998 and Brazil in 1999 — and as it had for Europe both financially and militarily, in two world wars.

China previously has stepped in to offer loans to far smaller economies, including Portugal, Spain and Greece. It also helped investment banking giant Morgan Stanley stave off collapse by purchasing a large share at fire sale prices during the 2008 global financial crisis.

Italy’s appeal to China, however, signals something new.

The past three years have delivered a stark reality check to the American superpower. Offering financial help to even its closest allies these days would be an exercise in keeping up appearances. America — and Japan, Britain, France and, yes, even Germany, have their own deep financial problems.

Instead, the Italian-Chinese talks sparked a statement from Brazil’s finance minister announcing that the so-called “BRICS,” Brazil — Russia, India, China and South Africa — will meet on Monday to see what can be done for the sick man called “Europe.”

As the perpetual crisis in the most developed economies indicates, the world that emerged out of the cauldron of the American century is unraveling. The decline of U.S. economic and political influence is clear, as is the rise of the BRICS and other emerging powers. Much has been written about the policy mistakes, demographic problems and debt woes that beset the old “West” and its Asian protege, Japan.

But most analysts have underestimated the potential speed of American decline. Very few have grappled with the consequences for U.S. and its allies as the American-led status quo across the globe begins to fray and even break apart.

Do not be fooled: America’s global military dominance rests entirely on its ability to pay its bills. Military juggernauts with dysfunctional economies end up in the same predicament, most recently exemplified by the fall of the Soviet Union. By the time the USSR was declared dead, even the Soviet military — only 20 years earlier a match for any on the planet — had deteriorated to the point where recruits had starved to death at one military base; warships rusted at their moorings for years; and control of the military’s version of the crown jewels, the nuclear arsenal, was seriously under threat.

No direct comparison can be drawn between the incompetence of Soviet state central planning and the flaws of American-designed global capitalism. The U.S., for all its mistakes over the past several decades, remains the vital player in global economics, and will remain the world’s largest for decades to come.

But therein lies the planetary danger: the Soviet economy’s collapse affected primarily a small group of similarly distorted economies tied to it through communism’s version of the Commonwealth — called Comecon. For Cuba, Eastern Europe, selected African despotisms and Moscow-friendly India, it was a disaster. For the rest of the planet, it was pleasant surprise and an opportunity.

In contrast, the U.S. economy is so large and the rest of the planet’s holdings of dollars and U.S. debt so endemic that America’s fate concerns everyone, friend and foe alike. China, Russia and the Gulf emirates fear an American debt default far more than American military might — as their chiding of U.S. fiscal prevaricating shows.

China has made similar appeals to European economic policymakers, urging them to put aside the domestic political concerns that so far have taken precedent in the rich E.U. countries, preventing a true solution to the tumbling dominoes of the euro zone periphery, the so-called PIIGS: Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain.

The U.S. and China, along with all major economies that depend on selling goods to the gigantic E.U. market, are terrified about the prospects of a “lost decade” taking hold in Europe. Such stagnation would further collapse demand and consumption that’s already struggling in the absence of the once-spend-happy American consumer.

Partly for that reason, last week the Fed and European Central Bank reestablished a “swap” capability so Washington could pump money into Europe’s banks if worst comes to worst — a move seen as crucial to Europe’s vast economy.

But politically, the implications are deep and so far unappreciated. Think of it: the uncontrolled unraveling of Lehman Brothers, a second-tier investment bank, nearly caused the global financial system to crumble in 2008. And now, the threat of default of a small sovereign player like Greece could destroy the European Union’s common currency. In comparison, the uncontrolled unraveling of U.S. power would be a disaster of global proportions.

Britain’s long retreat from global dominance in the early 20th Century sparked civil wars and left geopolitical Gordian knots like Kashmir and Palestine and Northern Ireland all over the planet. Likewise, the pull back of American power in our time will expose, for the first time in decades, parts of the geopolitical shoreline that American power, political will and diplomatic influence have heretofore sheltered.

It could be that the world suffers right now from a kind of “crisis fatigue.” After all, the spectacle of European economic powers appealing to China for massive purchases of their shaky government debt follows on some truly scary episodes:

- the effective bankruptcies of three European states — Greece, Ireland and Portugal, met feebly by European Union politicians with half-measures, parochialism and denial.

- the battering of Japan’s economy by a combination of natural, man-made and policy-induced disasters, a combination that has it well into a third consecutive “lost decade” of debt and low growth.

- the theater of the absurd in Washington, with know-nothing politicians threatening to default on the United States debt and sparking the richly deserved downgrade of its long-term credit rating from AAA+ to AA+ by Standard & Poors.

Well, sorry for the fatigue. But as the great Al Jolson said in 1927, on the cusp of another great calamity, “Folks, you ain’t seen nothing yet!”