When I hear people running down “60 Minutes” contributor Andy Rooney, who announced his retirement yesterday, I get as grouchy as Rooney did during his weekly pieces.

Granted, the perception of the CBS pundit as a gasbag who overstayed his welcome isn’t unearned. The sun didn’t rise or set based on whatever he said at five minutes to eight Eastern time each Sunday night, and during the final stretch of Rooney’s tenure — which started in 1978 and will end this Sunday with his sign-off — he didn’t exactly challenge himself to explore new frontiers. He stuck with what worked for him: griping about inflation or recession or political hypocrisy, admitting that he was out-of-touch and not losing any sleep over it, pointing out life’s annoyances and pleasures, opening his letters and packages on the air.

Along the way, Rooney ticked people off, and not always with his “60 Minutes” commentaries. His 2007 newspaper column about Latino players’ dominance of baseball (“I know all about Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, but today’s baseball stars are all guys named Rodriguez to me”) got him in trouble, as did his 1990 TV special “A Year with Andy Rooney,” which included off-the-cuff remarks describing “homosexual unions” on a list of “self-induced ills” that “kill us.” Rooney compounded that last scandal by giving an interview to The Advocate in which he allegedly said, “Most people are born with equal intelligence, but blacks have watered down their genes because the less intelligent ones are the ones that have the most children. They drop out of school early, do drugs and get pregnant.” I say “allegedly” because Rooney strongly denied saying those last couple of lines, and there was no tape of the interview. Was he lying? Maybe. But to my knowledge, he copped to — and apologized for — every other thoughtlessly offensive public comment he made, voluntarily or under CBS duress. “That’s what I do for a living,” he told the New York Times in a story about the baseball flap. “I write columns and have opinions, and some of them are pretty stupid.”

Well, sure. But many of them were amusing, in a beetle-browed grandpa sort of way. A few of them were poignant or provocative. And nearly all of them were well-written and sincere — punchy, economical, honest to a fault.

Rooney’s job on “60 Minutes” was to be himself and say whatever popped into his head. He was very good at it. The level of craft that he brought to bear on the low-stakes feature “A Few Minutes with Andy Rooney” is easy to take for granted. I don’t have much patience with anyone who dismisses Andy Rooney as nothing more than a bigoted old crank who had a cushy job on “60 Minutes.” People who would say such a thing don’t know much about Rooney, don’t appreciate the complexities and contradictions of the human personality, and don’t appreciate good writing.

Here’s a bit from an Andy Rooney column collected in his book “Out of My Mind.”

On television, the reporters pad their parts by saying things like, ‘There will be an accumulation of eight inches of snow on the roads tomorrow morning during rush hour, so allow yourself extra time and drive carefully.” Has any driver in history driven more carefully because of being admonished to do so by a radio or television announcer?’

The traffic reporters and weather experts both give a lot of advice. The traffic reporter will say, “There’s a four-car pileup with an overturned tractor-trailer on I-90, so stay to your right.”

The other advice they give, as though they were being helpful, is to travelers: “Kennedy Airport is closed to all traffic, so call your airline in advance for flight information.” Have they ever tried to call an airline? Airlines don’t have people answering telephones. You have as much chance of getting information about a flight from an airline as you as you have of finding out whether we’re at war with Iran by calling the White House and asking to talk to President Bush.

That’s the Rooney style. It’s simple, direct and funny without trying too hard. You can hear him saying those words, or something very close to them, in a “60 Minutes” piece. His broadcast voice and his print voice are the same, and his extemporaneous speaking voice is very close to it. It’s an excellent voice for a professional curmudgeon whose job is to riff on modern life in two-minute televised bursts.

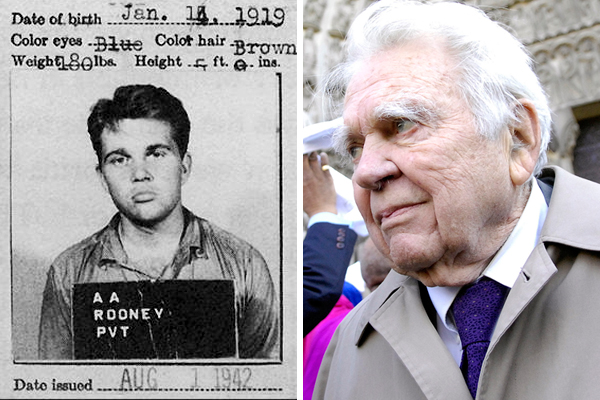

But it can also be applied to more serious, personal writing — as Rooney, a reporter for Stars and Stripes during World War II, demonstrated in 1995’s “My War,” one of the greatest firsthand accounts of the Allied experience in Europe. Rooney won a Bronze star for his reporting, which included accounts of the liberation of Buchenwald, the French Seconde Division Blindée’s ride into Paris, and the D-Day landing. Recalling the sight of thousands of dead soldiers sprawled on the beach at Normandy, he wrote: “I remember the boots. All the same on such different boys.”

From the book’s first chapter, “Drafted”:

War brings up questions to which there are no answers. One question in my mind, which I hardly dare mention in public, is whether patriotism has, overall, been a force for good or evil in the world. Patriotism is rampant in war and there are some good things about it. Just as self-respect and pride bring out the best in an individual, pride in family, pride in teammates, pride in hometown bring out the best in groups of people. War brings out the kind of pride in a country that encourages its citizens in the direction of excellence and it encourages them to be ready to die for it. At no time do people work so well together to achieve the same goal as they do in wartime, Maybe that’s enough to make patriotism eligible to be considered a virtue. If I could only get out of my mind the most patriotic people who ever lived, the Nazi Germans.

Rooney’s career was more varied and accomplished than some might realize. He started in television when television was just getting started. He wrote for “Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts” and CBS News’ public affairs program “The 20th Century.” He and his future “60 Minutes” colleague Harry Reasoner pioneered a new form of TV news writing that flowered briefly in the ’60s and ’70s, the long essay — a more complex and ambitious precursor to the bits he would do on “60 Minutes.” For his 1975 special “Mr. Rooney Goes to Washington,” he won television’s highest honor, the Peabody. Rooney wrote the script for the 1975 TV documentary “FDR: The Man Who Changed America,” and won an Emmy for writing the 1968 special “Black History: Lost, Stolen or Strayed,” part of a series of CBS specials titled “Of Black America.” When I met Kurt Vonnegut at college literary event in 1990 and asked him who he thought an aspiring writer should study, Andy Rooney was on his short list.

It was perhaps inevitable that Rooney would become associated with the ticking stopwatch of “60 Minutes.” The CBS News magazine, which debuted in 1968, was — and remains — the best-written news broadcast on TV. The correpondents’ copy was taut and lyrical and almost never overwrought. Their introductions and narration were composed in that clean, purposeful voice that dominated post-World War I journalism and fiction. The voice was embodied by the likes of Dashell Hammett, Dorothy Parker, Ben Hecht, Ernest Hemingway and E.B. White, but it was probably birthed by the invention of the typewriter. It was Rooney’s voice, too, and he wielded it with much authority and little fuss.

More than anything else, Rooney is a writer, and a good one. He didn’t become a pop culture icon because of his good looks or charming personality. He did it by expressing himself clearly and concisely, in language that connected with readers and viewers. He writes in the spare, mostly adjective-free style that was fashionable in the post-Hemingway era, and that you had to master if you wanted a job in newspapers. It’s a style that’s rarely seen today except in crime novels and certain big-city tabloids.

When I profiled Rooney for the Newark Star-Ledger in 1998, he brought me into his office and showed me his typewriter, a black Underwood that was older than the CBS News building that we were meeting in. It sat on a gnarled, vaguely Tolkien-esque desk that Rooney built himself. He said he’d been dragged into the computer age in 1989 because his bosses were tired of having to have interns key his typewritten scripts into CBS’ computer system, but that he still wrote personal letters and responded to reader mail on his Underwood.

“There’s really no good reason to keep using it,” he told me. “But I like the typewriter. I like the sound of it. When I write on a computer screen, I feel like the words really don’t exist. But when I write on a typewriter, they’re real.”

Rooney isn’t perfect. He isn’t always likable. Sometimes you wish he’d put a sock in it. His eyebrows are terrifying. But he’s real, uncomfortably real — maybe one of the realest Americans on prime-time TV, and the only one who continued to have a national platform into his 90s. Every family has at least one Andy Rooney in it — a person who’s lived a long and not always pleasurable life, and who has decided that from now on he’s going to say whatever he wants — and if you don’t like it, tough.

Reasonable people may disagree on whether Andy Rooney was funny, or whether he should have stayed on “60 Minutes” for as long as he did. But the man is a fine writer of a sort that is gradually disappearing along with his generation. His personality provokes debate. His talent demands respect.