I am delighted to receive such a thoughtful response by the distinguished philosopher Daniel Dennett.

Let me make one point clear at the beginning. Dennett, Dawkins and I agree that most religions have some beliefs that contradict science, and we also agree that religion has done harm in the world. The question is: What should be our attitude toward religion and toward individual people who have religious beliefs?

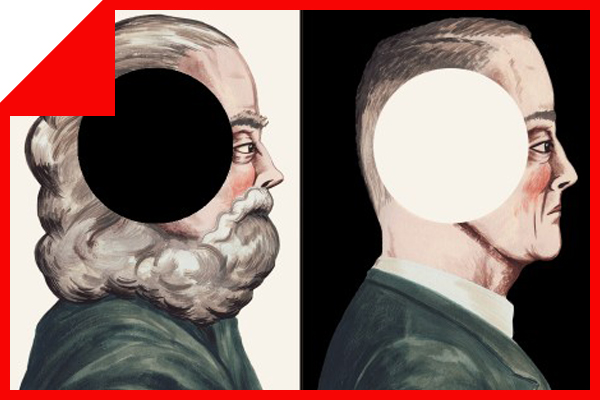

With regard to the meeting of science and religion, both Dennett and Dawkins take the stance of a strict dualism, an either/or position, a black and white portrait that I cannot accept. In fact, I would argue that such an absolutist position has some of the same problems as fundamentalism of any kind.

Dennett says that I am concerned that Dawkins is “too darned clear, too brutally frank when he articulates his case” against religion. It is not Dawkins’ clarity that concerns me. It is his condescension toward believers and his labeling of this large group of people as non-thinkers. In contrast to what Dennett suggests, I certainly do not take lightly the problems posed by today’s religions. We should continue to oppose religious practices that cause harm to other human beings, and we should continue to oppose irrational thinking on issues that require rational thought. But does this mean that we should dismiss believers as non-thinkers? There are thousands of intelligent, thoughtful and rational thinkers who also believe in God.

Dennett says that I am “letting off the hook” Frances Collins and Owen Gingerich – presumably by not actively contesting their belief in an intervening God who performs miracles. I clearly state in my essay that I disagree with these scientists in this particular belief. But that does not mean that I consider Collins and Gingerich irrational people, or people who are somehow dangerous to our society, as Dawkins implies in his writing. Show me an instance where Collins or Gingerich has refused to accept a particular finding of science or been hindered in their scientific work because of their religious beliefs, and I would vigorously oppose them. Quite the contrary, these people have made valuable contributions to science and the history of science. Their ability to do so, in fact, demonstrates that religious beliefs and science can live side by side within the human mind. Have Albert Gore’s religious beliefs dulled his ability to think rationally and to work to protect the environment? Certainly, philosophers and other intellectuals, such as Dennett and Dawkins, should study and articulate what they consider to be logical and self-consistent systems of understanding. But we should also look at the evidence afforded us by real, practicing human beings, like Collins and Gingerich and Gore.

Dennett wants me to delineate my view of the boundaries of faith. I will do so. I oppose any belief that contradicts experimental evidence as determined by the methods of science. All beliefs not in such contradiction may be considered as faith. Whether faith in a particular belief is beneficial or not is another matter. For example, I would not embrace faith that mental concentration can affect the outcome of a coin flip, because experiments show that the distribution of heads and tails comes out in a random pattern regardless of the wishes of bystanders. On the other hand, I would consider as legitimate faith the belief that some intelligent being created the universe or that our lives have a meaning, because those beliefs have not been disproved by science.

Dennett says that because I have commented that some of the great works of art were inspired by religion, I imply that atheists (of which I am one) are “a philistine lot.” Surely, as a philosopher, Dennett knows that a statement does not imply its inverse. “If you are religious, then you create art,” does not imply “If you are not religious, then you do not create art.”

Finally, Dennett says that I “prefer to sing the praises of faith without holding it to account.” I’m sorry, but I do not think it is faith, as I define it in my essay and as I have defined it above, that has caused the sufferings of human beings through the ages. It is the lack of moral compass in individual human begins that has caused suffering.

Dennett reminds me that Richard Dawkins is deeply appreciative of the art, music and poetry that religion has engendered, but it is just that Dawkins believes that religion, on balance, has accomplished more harm than good.

I would find it difficult to attempt such a tally. Whatever the results of such a balance, does that mean we, like Dawkins, should throw out religion wholesale, take a condescending attitude toward people of religious beliefs, label people of religious beliefs as non-thinkers imperious to scientific evidence? No. It means that we should continue to oppose those practices of religion that do damage, we should continue to oppose irrational thinking on issues that require rational thinking and evidence. But, at the same time, I would argue that we should allow our existence to encompass some things that we cannot explain by rational argument and proof.

We live in a highly polarized society. We need to try to understand each other in respectful ways. To that end, I believe that we should make room for both spiritual atheists and thinking believers.