It’s fair to at least wonder whether the unanimous opposition of Republicans to practically everything Barack Obama says and does is a product of authentic ideological disagreement or disingenuous political strategy. Probably it’s a combination of both, and this by itself isn’t a revelation. Opposition parties tend to blow up minor disagreements with presidents and to invent brand new ones (Democrats have done this too), and certainly there are areas today where a clear, long-established philosophical divide between Obama and the GOP really does exist.

What does feel different, though, is how often we’ve heard Obama-era Republicans frantically sound the alarm over ideas that they themselves once embraced. The rendering of the individual healthcare mandate, a concept with deep conservative roots and one that numerous GOP member of Congress actively pushed for in the mid-1990s, as a jobs- and freedom-killing abomination is a good example of this.

Another, as it turns out, involves tax fairness. The outcry from the right over Obama’s renewed insistence that the wealthiest Americans assume a slightly higher tax burden has been fierce and unrelenting. In particular, Republicans have attacked Obama’s endorsement of the principle behind the “Buffett Rule,” the notion that it’s wrong that the super-affluent are able to pay a lower effective tax rate than the middle class if they derive most of their income from investments.

Granted, Republicans, at least since the advent of supply-side economics and the election of Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, have tended to be more protective of the wealthy when it comes to crafting tax policy. But they’ve also tended to be flexible. Case in point: Reagan’s campaign for tax reform in the mid-’80s, during which he blasted “crazy” and “unproductive” tax loopholes that “allow some of the truly wealthy to avoid paying their fair share.” A clip of the Gipper making that argument has been circulating online since last week.

But it’s another episode, from the more recent past, that offers even better reason to view the GOP’s current Buffett rule posture mainly as a cynical ploy.

It comes from the 1996 Republican primary season, when the party was searching for an opponent for Bill Clinton. Bob Dole, then the Senate majority leader, was the clear front-runner, and in the early going Texas Senator Phil Gramm (“I was conservative before conservative was cool”) was seen as his chief rival. Pat Buchanan, with his populist “American first” message, and Lamar Alexander, who pitched himself as an electable Washington outsider, were also in the mix.

Then along came the publishing magnate. Steve Forbes entered the GOP race late, at the end of September 1995, and with virtually no name recognition outside the Manhattan publishing world. But he was willing to use his own money and ready to spend more than any other candidate. His plan was to build his campaign around an idea with broad superficial appeal: a 17 percent flat federal income tax rate.

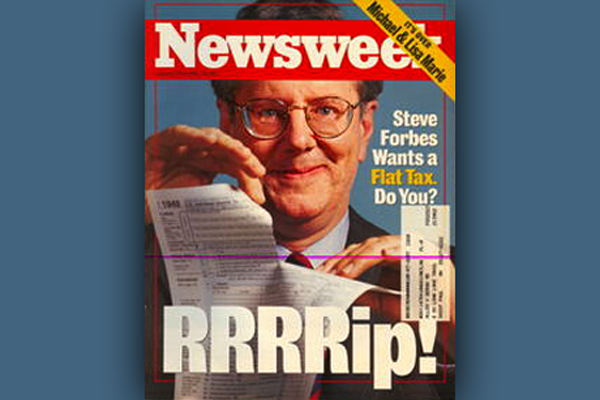

Forbes launched a lavish advertising campaign decrying the IRS and touting his own plan’s simplicity (you’d be able to do your taxes on a postcard!) while promising that it would unleash torrential economic growth. The idea, and Forbes, caught on. He began moving up in polling and attracting serious press coverage (like the Newsweek cover story that you see at the top of this piece). By January, he’d actually taken the lead in New Hampshire and had become a legitimate threat to win the nomination.

Which is when his fellow candidates started paying a lot more attention to him and to his flat tax plan. The attacks that they launched are notable in that they ran counter to just about everything the GOP now says about taxation and the wealthy and “class warfare.”

Take Gramm, who was positioning himself as the “pure” conservative in the race and offering a flat tax of his own. But there was a difference: His plan would still tax capital gains income, while Forbes’ wouldn’t. Gramm decried this as a politically suicidal giveaway to the rich, one that would sentence Forbes to a landslide November defeat if the GOP were to nominate him.

“There’s no doubt about the fact you could buy every ad on the Super Bowl,” Gramm said, “and you could never convince the American people that you ought to have a 17 percent tax on wages and salaries, but much of investment income should go untaxed.”

Gramm launched an ad that made the same point: “A flat tax? Good idea. But Steve Forbes and Phil Gramm differ on what’s flat and what’s fair.”

Forbes’ other rivals made the same argument. Alexander derided the Forbes plan as a “nutty” product of Forbes’ “penthouse” lifestyle. Dole was more direct: “All you people who go to work in a helicopter, vote for Forbes.”

“There’s nothing President Clinton would like more than Republicans to adopt a flat tax as part of their 1996 election strategy,” he said. “He can go out and make the case day after day after day, ‘Here they go again, helping the rich. Helping the Malcolm Forbes(es) of America.'”

These attacks and others ended up wearing down Forbes, who finished fourth in Iowa and New Hampshire, briefly revived his campaign with an upset win in Arizona, then fizzled out for good.

What’s notable in looking back, though, is that Gramm, Alexander and Dole were all essentially endorsing the Buffett Rule. But just 15 years later, that position is now regarded as heresy in the GOP. To be fair, some Republicans did defend Forbes and his plan back in ’96, but given the history, it’s hard not to conclude that the party’s new anti-Buffett consensus is mainly a product of Obama’s association with it.

Just consider the case of Buchanan, who remains a prominent voice in politics today. On the McLaughlin Group recently, he asserted that the Buffett Rule is “rooted in the philosophy of envy.” He could have added, but didn’t, that it’s also rooted in the Buchanan ’96 campaign platform, because back then he savaged the Forbes plan, claiming that it was “worked up by the boys at the yacht basin.” And he introduced his own version of the Buffett Rule. “David Rockefeller,” Buchanan declared, “could move to Florida and pay less in taxes than the guy who’s serving him drinks.”