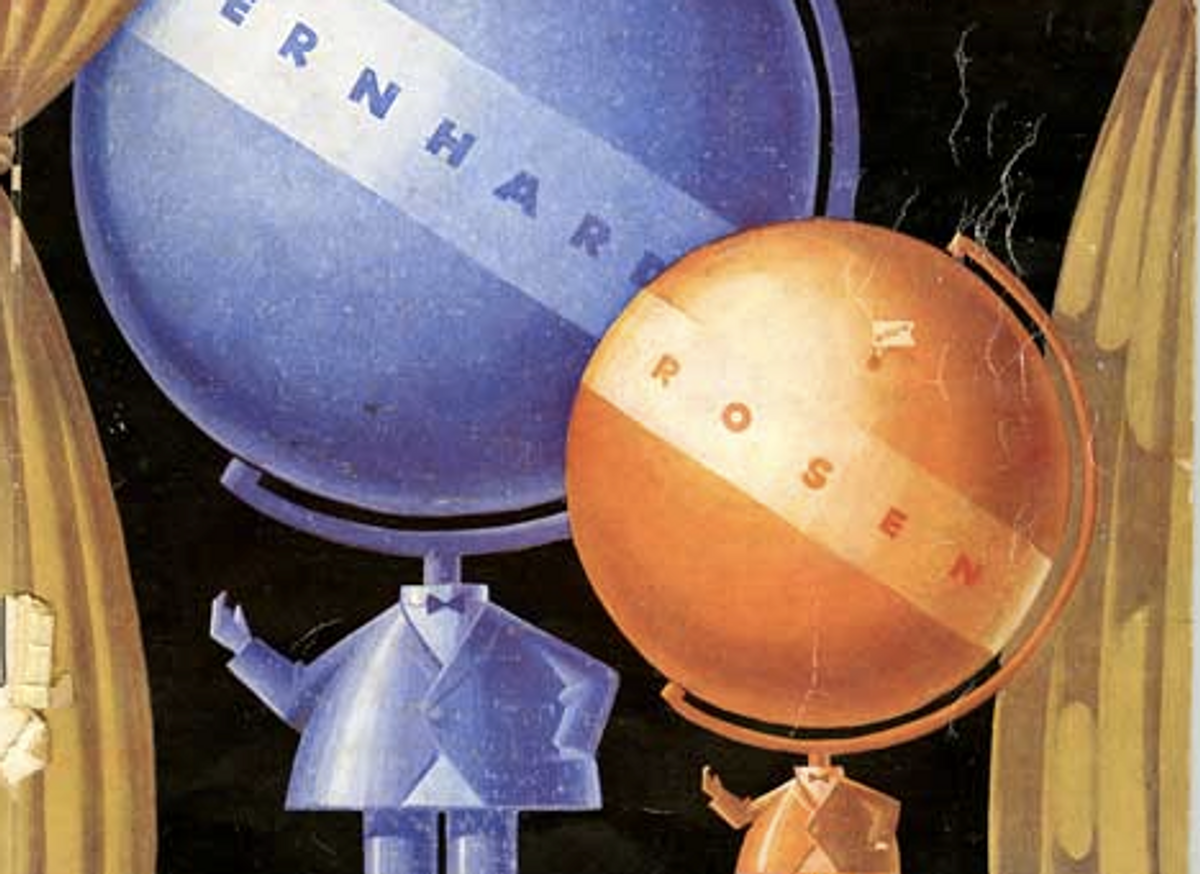

Lucian Bernhard (1883–1972) is the father of the modern advertising poster known as the sachplakat or “object poster.” He was based in Berlin, but moved freely between New York and there, finally settling in Manhattan in the mid-1920s. Around that time Gebrauchsgraphik, the leading German advertising design magazine, devoted part of an issue to Bernhard and his Berlin Partner, Fritz Rosen. The interview is one of the few documents (apart from personal correspondence) to shed light on his transition from German to American graphic idioms. Bernhard eventually developed an impressive American clientele, including Amoco and White Flash gas, Cats Paw, and ExLax. In this excerpt from an interview with Oskar M. Hahn, Bernhard talks about where he set up his studio in the heart of New York and the difficulties in setting up his style. Here also is a podcast of my own talk on Bernhard's legacy.

Lucian Bernhard (1883–1972) is the father of the modern advertising poster known as the sachplakat or “object poster.” He was based in Berlin, but moved freely between New York and there, finally settling in Manhattan in the mid-1920s. Around that time Gebrauchsgraphik, the leading German advertising design magazine, devoted part of an issue to Bernhard and his Berlin Partner, Fritz Rosen. The interview is one of the few documents (apart from personal correspondence) to shed light on his transition from German to American graphic idioms. Bernhard eventually developed an impressive American clientele, including Amoco and White Flash gas, Cats Paw, and ExLax. In this excerpt from an interview with Oskar M. Hahn, Bernhard talks about where he set up his studio in the heart of New York and the difficulties in setting up his style. Here also is a podcast of my own talk on Bernhard's legacy.

[The interview begins with Herr Hahn's brief introduction.]

Times Square is the focal center of the life of New York. Here, where Broadway and Seventh Avenue cross Forty-second Street, lies the amphitheater of those gigantic electric advertising signs which convert night into day and draw their immense crowds – composed of all the peoples of the earth – into their magic circle, night after night.

The Times Building is a slender tower that rears into the heavens above the human pandemonium in the very center of the street crossings. This building is now devoted entirely to the advertising department of the New York Times – the newspaper itself is produced in the Times Annex Building which is “only” fifteen stories high, in a side street not far off Broadway. It is one of the upper stories of this building that Lucian Bernhard has established his studio.

There is an artificial stone floor of a brilliant blue color, surrounded by a baseboard molding of old gold. The walls are about seven feet high, of a yellowish white, and of a very rough texture, resembling the surface of a cut of Roquefort cheese. This wall is surmounted by a projecting undercut surface of transparent cloth which hides the source of light that illuminates the walls and the many reproductions with which these are decorated. The fascia of this undercut forms a very marked profile in blue and gold. Above this the ceiling looms invisible in an impenetrable black.

This is the Exhibition Room, into a corner of which the circular private office has been built. This is surmounted by an onion-shaped “roof” – the inner walls and ceiling are red and rose and decorated with painted designs. The contrast afforded these two rooms opening into each other is the actual workshop of the artist, from the windows of which a characteristic perspective over the roofs of western New York unfolds itself towards the Hudson.

I owe this precious place in the heart of New York to the kindness of Mr. Adolph Ochs, the well-known proprietor of the New York Times, who is greatly interested in my decorative style,” said Herr Bernhard. “I am going to have exhibitions here from time to time of all my different branches of work. What branches? Well, the same as in Germany – posters, packings and trademarks, letter-press or lettering, the furnishing of houses, restaurants, exhibition rooms, etc.”

Do you design these in the same style you used in Germany, or have you altered your style?

I always imagine that I design these things in the same style I used in Germany, and yet when the work is done, I realize that I would certainly have designed it differently in Germany. Thus, my adjustment to the American atmosphere is not an intentional but an unconscious one. I am moreover convinced that deliberate adjustment would be impossible. The two years I have spent here have convinced me that American psychology cannot be learned – one can only assimilate it by breathing it. And the fewer ready-made judgments a man brings with him over here, the more easily this process takes place.

Don’t you think that the style which you cultivated in Berlin would be the best means of your attaining success here?

The exhibition of my German work has brought me whole-hearted recognition form the American advertising experts. And yet when commissions are given, a distinct departure from this work is always demanded. This is due, firstly, to the fact, even though this fact is not mentioned, that I am regarded as one of the most pronounced exponents of German poster art, and one is afraid that an unadultered German poster style might unfortunately, arouse political offense among a great part of the American public. Then again, one must deal with the fact that public taste has been vitiated and misdirected for so many years through the one-sided use of posters based merely upon the enlarged photograph, that nobody has enough artistic courage to come forward with a strong, simple and actual style of poster art. It is nevertheless trud that America may boast of a sufficient number of first-rate artists who are admirers and followers of the European poster, as, for example, C.B. Falls, Joseph Sinel, Jack Sheradon, etc., thought these men are seldom given an opportunity to appear before the public with a poster of their own. A specimen of the work of Will Bradley and Edward Penfield, those founders of American poster art, has not been seen for at least a decade. I’m glad to see that Hohlwein of Munich is now represented on the New York billboards by a number of his own postsers. He is the European artist who is best able to fulfill the demands which the American public makes upon the realistic illustrated poster, and he thus represents a bridge between American and European conceptions in this field. His posters for ‘Fatima’ cigarettes have attracted great attention and have met with general appreciation.

Do yourself make any concessions to American taste?

I am unconsciously, as I have already said, very much influenced by the atmosphere in which I work. But the results cannot properly be described as having been due to such influences, for here, precisely as in Berlin, I create only such things as satisfy me personally and give me joy. Nevertheless I have not yet approached as closely to what the American people really want, as Hohlwein has succeeded in doing with his original Munich posters. The American wants a ‘picture,’ an ‘idea.’ A purely optical idea is not idea at all for him. He demands what he calls ‘human interest’ in his posters. If he can get this, and get it intensified by strong and piquant color effects and cool composition, so much the better, and its is these factors which they so justly admire in the work of Ludwig Hohlwein. A Hohlwein poster in New York does not make the impression of being anything alien – it is merely much better than most of the others.

Do you think that in spite of these difficult circumstances, you will be able to make a place for yourself?

No doubt of that. Why, the mere demand for variety helps me to succeed. But style, as I have already remarked, cannot merely be imported. It must be transfused with an American atmosphere, if it is not to operate as a foreign body.

(See the link to Leo Sorel's film on Ed Sorel at The Weekend Daily Heller here.)

Copyright F+W Media Inc. 2011.

Salon is proud to feature content from Imprint, the fastest-growing design community on the web. Brought to you by Print magazine, America's oldest and most trusted design voice, Imprint features some of the biggest names in the industry covering visual culture from every angle. Imprint advances and expands the design conversation, providing fresh daily content to the community (and now to salon.com!), sparking conversation, competition, criticism, and passion among its members.

Shares