How much do you know about the 19th-century American illustrator whose work left Vincent van Gogh “dumb with admiration”?

Even if you’ve never heard Howard Pyle’s name, it’s more than likely that his fervent, imaginative visions have played a role in your cultural intelligence.

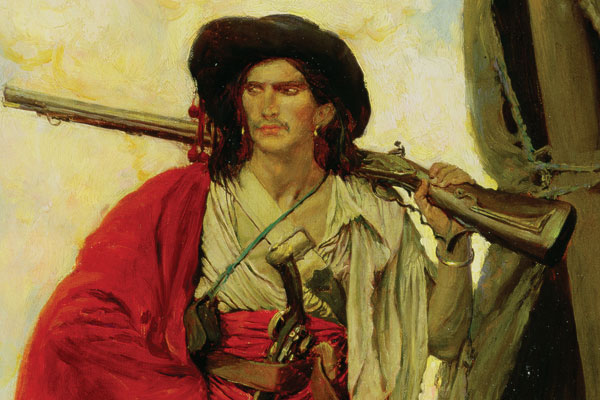

Born in Wilmington, Del., in 1853, Pyle lived to become one of his century’s most celebrated illustrators. His contributions were not limited to the visual arts; indeed, his adaptations of classic myths — such as the stories of King Arthur and Robin Hood — were influential additions to the Western literary canon. And fans of pirate movies (old-fashioned or brand-new) have a good deal to thank him for: His splendid, fantastical incarnations of sea-bound bandits are cited as inspiration by major artists and filmmakers. (A 2007 Chicago Tribune piece testifies to the fact that “Pirates of the Caribbean” creators and costume designers turned to Pyle for guidance when crafting their blockbuster buccaneers.)

Shortly after Pyle’s death in 1911, a group of his friends came together to form the society that would eventually become the Delaware Art Museum. One hundred years later, that museum has launched a retrospective, seeking to put Pyle’s work in context and delineate the artist’s influences. (Among Pyle’s sources, the exhibition explains, are pre-Raphaelite tableaux and Japanese woodblock prints.)

Over the phone, curator Margaretta Frederick answered some of my questions about Pyle’s work; an edited transcript of our conversation is below. Check out the following slide show for a selection of Pyle’s own sublime images.

The title of this exhibition is “Howard Pyle: American Master Rediscovered.” Why “rediscovered”? Do you think there’s a sense in which his work has been lost?

Sometime around the turn of the century, illustration got written out of the history of art. For lots of reasons: its commercial associations, the advent of photography. Illustration got sidelined as kind of a poor, younger sister to the fine arts. So the premise of the exhibition is to suggest that despite the fact that Howard Pyle is normally only looked at as an illustrator, he was as aware of — and as much a participant in — the art of his time as any of the fine artists. That’s why in the exhibition we’ll be using comparisons of works by other artists to show that Pyle was engaged with the art of his time.

Is there an artist working today who spans the genres of fine art and illustration in the way that Pyle did?

You know, before, illustration was it. It was your TV, your movie; it was the visual entertainment. I’m not sure we think about illustration that way anymore. At least at the time that Pyle was beginning, there were artists working in both fields, and that was OK. But as I said, somewhere around the turn of the century, it started to get more segregated — and there wasn’t much of a crossover. I think there are contemporary fine artists now who do do illustration in addition to their other work — but they are fine artists first.

It seems like Pyle had an active role in shaping our understanding of classic Western tales — his illustrations of romantic, fantastical characters, like pirates, have had impressive cultural staying power. How has Pyle shaped the stories that we know — or shaped the way we envision certain sorts of things? Have people who may not have actually heard of Pyle still been influenced by his work?

Well, certainly in terms of what the average person on the street today thinks of as a pirate, that image was something that Pyle conceived. Because there wasn’t that much documentation of what pirates wore, much of it was Pyle’s creation. Early moviemakers looked to Pyle’s illustrations when they were creating, for instance, the Errol Flynn movies; modern-day filmmakers do the same — [as in the case of] the “Pirates of the Caribbean” movies. I mean, it’s documented fact: The creators of “Pirates of the Caribbean,” for instance, talk about looking at Pyle’s work — because that’s what we all think pirates look like. That’s definitely from Pyle.

What Pyle did with things like the Arthurian tales was to retell them for an American audience (in this case, of course Arthur was a British figure). That’s something slightly different. But yes, I would think most Americans, when they think about Arthur, are thinking about Pyle’s illustrations — not an English version.

Were these normal late-19th-century preoccupations? These historical, romantic themes?

With pirates, I think Pyle’s pretty much got a clamp on the market for originality. But in terms of looking at the past, and romanticizing it, that’s something that was going on [more widely] — for instance, with ancient scenes: That subject was very big in the academies in Europe, and Pyle was certainly looking at the works of the artists like Jean-Leon Gerome in France, or Lawrence Alma-Tadema in England, both of whom were doing scenes from the classical world.

Of course, Pyle’s an illustrator, so there’s a demand for these. There’s some text that requires these illustrations. This is more of a Western-world cultural happening, this romanticizing of the past in the late 19th century.

Some of Pyle’s illustrations also deal with American history [slides nine and 10]. Where did the inspiration for these come from?

The Thomas Jefferson picture [slide nine] was an illustration for the history of the American revolution written by Henry Cabot Lodge. There is this moment — and it’s actually around the time of the colonial revival in the United States — when America as a country is starting to look at its early history. Pyle’s illustrations, Henry Cabot Lodge’s books — this is all part of a new-found, nationwide interest in the early history of the country.

My final question is about the Delaware Art Museum itself. It’s directly linked to Howard Pyle and his career, right? Can you give a little bit of the background?

Towards the end of his life, Pyle got very interested in mural painting. And there was a big movement in American art for public mural painting. Pyle decided he needed to go to Europe to learn more about mural painting (he had actually completed a couple of commissions before he went). It’s interesting because he was largely self-taught or [U.S.-trained] up until this point; he hadn’t gone abroad [for instruction] like many of his contemporaries. But then at the very end of his life, he decided to do that.

So he went to Italy, and he was there for a very short time, and he died of some sort of a liver complication — it’s not really clear at this point. At any rate, he dies — it’s 1911 — and he’s left a studio full of work here in Wilmington. A group of his friends and citizens in Wilmington got together and made sure many of those works were kept for the Wilmington public. They called themselves the Wilmington Society of Fine Arts; there was no building — they exhibited first, I think, in the Hotel DuPont in downtown Wilmington. They also exhibited in the top of the Wilmington Library, and then eventually, in 1935, when a gift of land and an additional collection of pre-Raphaelite art were given, they built a building. Then the Pyle paintings came to where they are today on Kentmere Parkway. But the museum begins with Pyle’s death, really.

“Howard Pyle: American Master Rediscovered” will be on view from Nov. 12 through March 4 at the Delaware Art Museum in Wilmington, Del.