On Monday, the Dow Jones industrial average fell 300 points, a plunge immediately blamed on the supercommittee’s failure to agree on a debt reduction deal. If this is true, investors were displaying a remarkable lack of attention to current events. Is there anyone on Wall Street or in Washington, D.C., or anywhere else who expected the supercommittee to succeed? Failure should already have been “priced in” by the markets. As anticlimaxes go, the only surprising thing about the supercommittee’s impotence is that anyone was surprised by it.

The most obvious proof that investors aren’t really alarmed by the prospect that partisan political gridlock will continue as least until the end of 2012 comes from the bond market. U.S. Treasury yields fell again, probably because investors who are continuing to be spooked by Europe’s sovereign debt woes are looking once again for the safest place to put their money. Despite all its faults, the U.S. economy is still growing faster than Europe’s, and the prospect that we will default on our debts still seems to be much lower than the chances that Europe won’t fix its own mess.

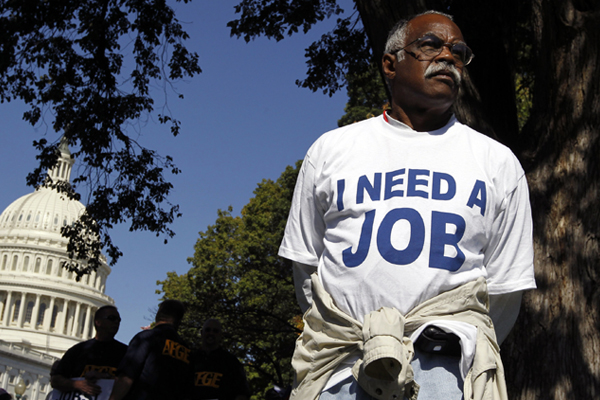

But that’s not to say that there won’t be economic fallout from this not-so-epic fail. If no action is taken by the end of the year, both payroll tax cuts and extended unemployment benefits will expire for millions of beleaguered Americans. That’s the definition of anti-stimulus, hitting American consumers directly in the pocketbook. Tuesday’s unexpected downward revision of the third quarter GDP growth estimate from 2.5 to 2.0 percent — a definite wet blanket stifling the more optimistic perceptions of the economy that had been percolating in recent months — emphasizes the risk. According to various estimates, the expiration of the payroll tax cut and extended unemployment benefits will together cut another 1 percent or so off of GDP growth. That will put the U.S. economy back perilously near a full standstill.

If it seems strange to be bemoaning a debt-reduction committee’s failure to extend a payroll tax cut and a social safety net benefit, both of which would obviously increase the deficit, well then, consider this: The biggest roadblock to getting a deal cut was Republican insistence on keeping all the Bush tax cuts in place. Indeed, the final GOP proposal actually pushed for lowering the maximum tax rate on the wealthy even further. But the long-term negative deficit reduction implications of keeping the Bush tax cuts in place for the wealthy dwarf the budgetary impact of the short-term measures that would help middle- and working-class Americans.

Tax cuts for the wealthy don’t give you as much stimulus bang-for-your buck (the rich are more likely to save their windfalls rather than spend them). So what this means is that the real impact of the supercommittee’s failure is that instead of providing short-term help to people who most need it, which would spur economic growth, Republicans have stood by their determination to keep tax cuts in place that will do the most long-term budget damage, while benefiting the people who least need it.

There’s no reason to be surprised by this outcome. But we can still get hopping mad about it, if we want to.