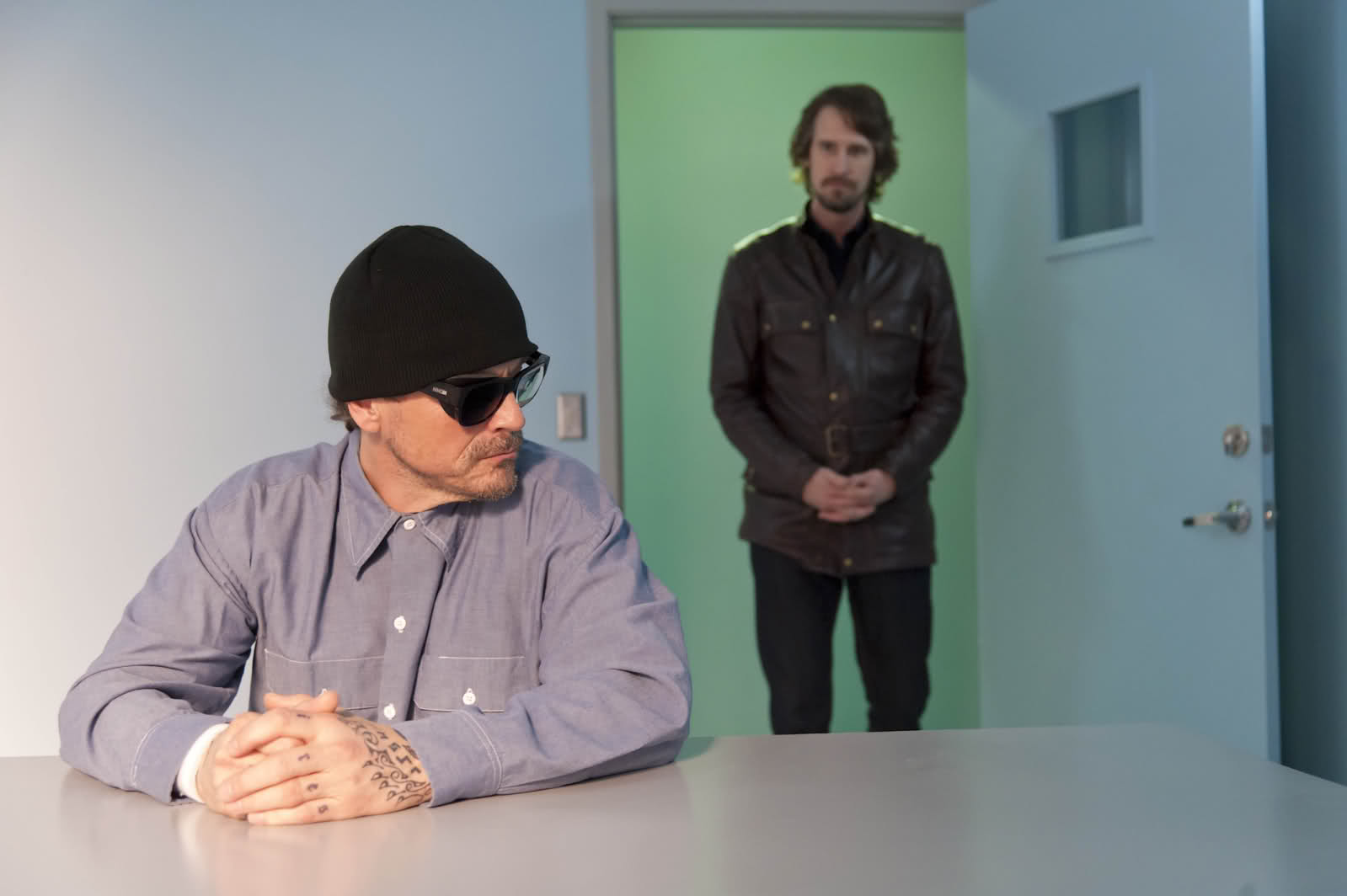

When Charles Dickens was at the peak of his popularity, Americans used to wait on East Coast docks for the latest chapters of his serialized novels to arrive. TV dramas are our version of that. The best have that mix of shamelessness and sophistication that Dickens refined into art — or at the very least, artful melodrama — and the FX biker drama “Sons of Anarchy” is right up there in the pantheon. Its cliffhanger episode endings are among the most addictive I’ve seen, and last night offered a great example: a three-way standoff between the increasingly evil gang boss Clay Morrow (Ron Perlman), his disaffected lieutenant Jax (Charlie Hunnam) and the vengeful Opie (Ryan Hurst), who discovered his dad’s reeking body and was informed that Clay secretly killed him. Everything about the standoff was utterly shameless: the race-to-the-finish-line lead-up; Opie’s tearful speech; Opie leveling his gun at Clay at the precise moment when Jax burst in and screamed at him to drop it; the shot of Clay’s body slamming against a wall; Jax’s horrified close-up. Cut to black, roll credits. Is he dead? Was he wearing a bulletproof vest?

I laughed out loud at this ending. It was primordially manipulative. It reminded me of watching old “Captain America” serials on local TV as a kid. (Me: “Mom, is Captain America going to get cut in half by the buzz saw?” Mom: “I guess you’ll have to watch next week to find out, but for now I’ll just remind you that the thing is called ‘Captain America.’) It also parallels nicely with the adventure tales I’ve been reading to my young son at bedtime — the kinds of books that’ll end chapters with sentences like, “He held his sword in front of him, moving slowly down the long, dark hallway until he pushed open the door and revealed the most horrifying image imaginable.” My boy’s reaction to these Big Reveal is always the same: “Daddy, what happens next? Can we read just one more chapter?”

“Sons” operates on that level. If you didn’t already know that series creator Kurt Sutter learned his trade on FX’s cliffhanger-driven, plot-crazy “The Shield,” you might have figured it out eventually. The show already did a similar cliffhanger ending this season in the episode where Juice, besieged on all sides and deeply conflicted in his loyalties, wrapped a chain around his neck, climbed up in a tree and tried to lynch himself. The second his body dropped, the episode cut to black and rolled credits. If you had keen ears you probably caught the sound of the branch breaking, but if you didn’t, you had a reaction similar to my childhood distress at seeing Captain America lashed to a giant log in a sawmill. Oh, my God, they killed Juice!

At the same time, though, the series subverts its wild melodrama and dense thriller plotting with flashes of moral ambiguity and self-awareness. You root for these people as if they were your best friends, until the show makes you take a step back and admit how depraved and sickening they are. The sheer goofy intensity of the internal warfare this season has been addictive and oddly moving — especially the parts that dealt with the half-black Juice’s distress at being pulled into finkdom by the town’s new sheriff; Gemma (Katey Sagal) raging like a material warrior-queen at Clay’s viciousness and stupidity while simultaneously feeding her narcissistic desire to be the center of the drama; and Tara (Maggie Siff) falling into black depression over the botched kidnapping that shattered her hand and ended her career as a surgeon. (The only silver lining for Tara is that the accident seems to have cured her simpering doormat tendencies: whether she’s talking to Gemma, Jax or — in this episode — the glowering, super-scary Clay, she stares right into their faces with scorn instead of fear.) Season four of “Sons” is neck-and-neck with two in my season rankings, and it might claim the top slot depending on what happens next week. It’s top-shelf pulp.

Where do we go from here? Although I wouldn’t put an improbable last-minute save past Sutter and his writers, I suspect Clay’s a goner, and that the season finale will find Jax forced to choose between leaving Charming with his wife and family versus pulling a Michael Corleone and assuming control of the suddenly rudderless SAMCRO. (Jax is unquestionably the best leadership candidate now that Mark Boone’s Jr.’s Bobby Munson is in jail, courtesy of a vengeful sell-out by Kurt Sutter’s incarcerated Otto.)

But whether “Sons” kills off Clay next week, waits until later, or lets him live, the show will have cemented its main theme: the gravitational pull of family, or more accurately, the abstract and unreal ideal of family, which is what all ragtag band of self-interested criminals really has.

Opie really shouldn’t even have been around the Sons anymore after losing his wife to them, but the allure of belonging was so powerful that here he was years later doing the “Fool me twice, shame on you” thing opposite Clay, who’s become one of the most loathsome bad daddy figures since Powers Booth’s Cy Tolliver on “Deadwood.” Gemma shouldn’t have stayed with Clay all these years; even when they showed deep love for each other — I loved Gemma’s kiss-off of a kiss in this episode — they were both still a couple of slimy criminals who were ultimately inclined to look out for number one, and Gemma usually seemed to get the worst of the arrangement. And yet here she is trying to be a good Lady Macbeth — stirring every available pot for the good of the club, but really for the good of Gemma. Jax is theoretically tied to the club forever by his father’s legacy, but he really means it when he says he wants out; unfortunately for him, on a show like “Sons,” that can’t happen. A leopard cannot change its spots, nor a biker his patches.

“Sons” isn’t a deep show and really isn’t striving to be one, but for a testosterone-poisoned potboiler, it’s complex and surprising. It lulls you into adopting the self-flattering points-of-view of the Sons of Anarchy motorcycle club and its individual members, then suddenly drops in a scene in which an outsider injects a harsh dose of reality, forcing the characters (and you) to admit that most of these characters are scummy, selfish and often incredibly flaky people, and that if you weren’t experiencing the low-grade version of Stockholm Syndrome that comes from committing to a weekly series, you wouldn’t want to be near any of them. The scene in the baby mill — thunderous punches competing with the mewling of panicked infants — was a hilarious example of this: the Sons can’t seem to go anywhere without getting into a brawl or shooting somebody. Clay’s self-satisfied grin at being told that the brawl actually benefited the Irish Kings reminded me again of what a colossal screw-up he’s been this year; he and the club have made one idiotic and self-destructive decision after another, yet somehow they keep getting saved from themselves, and they usually seem to think it’s because of their innate bad-assness and fidelity to a code instead of recognizing it for what it is: sheer dumb luck.

A great example is the scene in last night’s episode between Jax (Charlie Hunnam) and Wendy (Drea de Matteo), the ex-junkie mother of Jax’s son Abel. She’s cleaned up and wants custody again. She tells Jax, “You’re a felon on release, and as frightening as this notion may be, I’m probably the most stable adult in Abel’s life.” Because we identify with the gang and consider everyone outside of it to be a menacing interloper, we sympathize with Jax’s appalled, defensive reaction. But of course she’s right. Their parting exchange could be read a couple of ways, neither of them flattering to Jax. Wendy: “I ain’t goin’ anywhere.” Jax: “It’s OK — I am.” Jax is an awfully literal guy, but I think that last line intentionally had at least two meanings: (1) I am going somewhere as a person, and you’ll always be a junkie tramp, and (2) I am literally going somewhere, meaning out of town with my family, leaving the Sons and you behind. The nagging suspicion that he’s wrong on both counts gives the graphic novel-goofy “Sons of Anarchy” a certain tragic weight. Jax, the poor bastard, is just like all the other Sons: he rides thousands upon thousands of miles, cheating death at every turn, but in the larger, personal sense, he never gets anywhere.