“There was a time, before photography got discovered and revered as art, that everybody knew who the good photographers were. The people who cared about photography and knew all the photographers knew who the good ones were. And you could rank them in order, and move the order around according to what they had shot most recently. There was unanimity—a consensus of their colleagues about who was really taking telling pictures. I’m not sure that there’s the same consensus today, or the same knowledge of what’s out there and who is good.”

—from an interview with John Loengard by David Schoenauer

I went to the Leica Gallery on a recent Saturday afternoon for the “75 Years of Life” show, to see original prints of iconic photographs by Alfred Eisenstaedt, Margaret Bourke-White, John Dominis and many others whose work defined the silver age of black-and-white photojournalism.

I went to the Leica Gallery on a recent Saturday afternoon for the “75 Years of Life” show, to see original prints of iconic photographs by Alfred Eisenstaedt, Margaret Bourke-White, John Dominis and many others whose work defined the silver age of black-and-white photojournalism.

Just as anticipated, I escaped from the hordes of holiday shoppers on lower Broadway into a tranquil atelier that’s dedicated to celebrating the almost-lost art of the image as captured on black-and-white film and printed in the darkroom on photographic paper.

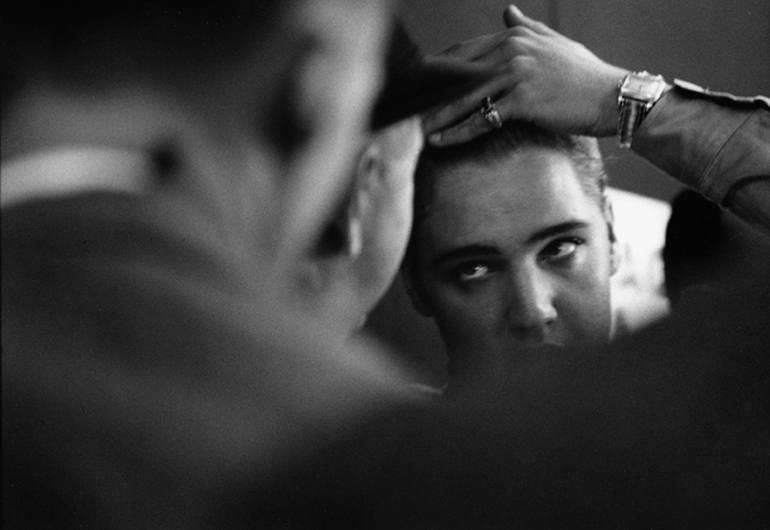

All the pictures were there, ready to be studied up-close and personal, with no lines, crowds or admission fees. Just me and one other visitor with the Kennedys and Marilyn and Elvis, heads of state and Hollywood royalty, Babe Ruth and Billie Holiday, Depression-era families, concentration camp survivors and military heroes, and Eisenstadt’s VE-Day Times Square kiss.

(David Goldman)

(David Goldman)Bill Ray: Elvis Presley, 1958, from "75 Years of Life"

(AP)

(AP)John Loengard: Brassai's Eye, 1981

What was not expected was to get really energized by a complementary exhibit of images by famed Life photographer and photo editor John Loengard, and then to meet Loengard himself. Celebrating his new book, “The Age of Silver,” the Loengard show presents 24 thought-provoking pictures of photographers working on location and in their studios. Over his 55-year career, Loengard interviewed and photographed Eisenstaedt, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Richard Avedon, Berenice Abbott, Harry Benson, and many others. There is the astonishing picture of Annie Leibovitz out on a Chrysler Building gargoyle as an assistant hands her a camera back freshly loaded with film, and there is Jay Maisel hanging from a water tower, solo, getting the shot.

Those pictures made me nostalgic for the days when graphic designers pored over contact sheets and sent out negatives to be printed at labs. Do other designers mourn the qualities of film photography that may never be captured again, while acknowledging that our survival would be impossible today without the access and speed of digital?

(AP)

(AP)John Loengard: Jay Maisel 190 Broadway, 1981

I’d just finished jotting down facts about the Leica Gallery (3,000 square feet, 130 shows over 18 years, 40,000 visitors a year) provided by Rose Deutsch, who with her husband, Jay, has co-directed the gallery since it opened in 1993, and started talking with her about the inimitable qualities of film when Loengard walked in. Without putting down the box of photo paper he was carrying, he joined the conversation.

“What is it that’s missing from digital?” I asked. “Is it the grain, or the full tonal range from whitest whites to blackest blacks?” “Think of Jell-O,” was his answer. “Silver suspended in gelatin, emulsion on paper.”

Yes, but a more complete answer can be found in David Schoenauer’s extensive interview on La Lettre de la Photographie: “You had a century of black-and-white photographs, and its emphasis was on expression and gesture. If you wanted to photograph someone, say, typically in the act of living, you got a sense of who they were and what they were by how you depicted their body and the expression on their face. I think that’s one of the qualities of black-and-white photography that we became sensitive to. And this was something that color would not add to.”

Leica Gallery is more than a walk down photography’s memory lane. It is keeping alive those rare moments when the perfect expression and gesture were captured on film. Thinking a bit more about the quote with which I opened this post: Maybe only a few people know “who the good ones are” anymore, but in a world where almost everyone is a photographer and a publisher (a good thing, no?), we can still celebrate the work of the good ones from the past.

Located at 670 Broadway between Bond and Bleecker in Manhattan’s NoHo district, Leica Gallery is open Tuesday through Saturday from noon to 6 p.m. Most prints are for sale, priced between $800 and $2,000, framed. The “75 Years of Life” and John Loengard exhibits will close on Jan. 7.

Copyright F+W Media Inc. 2011.

Salon is proud to feature content from Imprint, the fastest-growing design community on the web. Brought to you by Print magazine, America’s oldest and most trusted design voice, Imprint features some of the biggest names in the industry covering visual culture from every angle. Imprint advances and expands the design conversation, providing fresh daily content to the community (and now to salon.com!), sparking conversation, competition, criticism, and passion among its members.