Make no mistake, Raymond Bonner’s new book, “Anatomy of Injustice: A Murder Case Gone Wrong,” is a movie idea begging to be greenlighted. It would make an ideal vehicle for Sandra Bullock (or maybe Julia Roberts), in a dirty blond wig, playing the tough but still idealistic defense attorney with a checkered past, alongside an unknown shoo-in for the supporting actor Oscar as the simple-minded handyman whose life she’s determined to save. Like a John Grisham novel, this story has an ass-covering posse of good ol’ boys running the rigged law-enforcement and judicial system in a small Southern town and a team of dedicated legal crusaders from outside who check into the local motel and sit cross-legged on the floor surrounded by boxes of files and takeout coffee cups. It’s a genuine whodunit, a page-turner and a tale of redemption. And it’s all true.

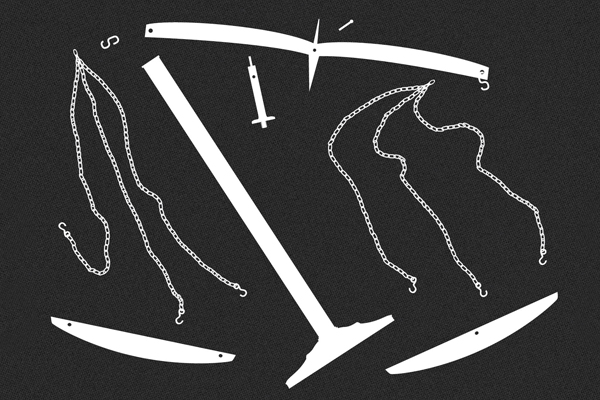

For all that, however, “Anatomy of Injustice” is also a blistering indictment of the death penalty. Assuming, dear reader, that you are yourself an opponent of capital punishment, it will only further cement your objections. It’s also a great book to hand to your less reflective or informed friends and relatives, the ones who may still support executions. Bonner, a Pulitzer-winning reporter who has long covered the issue for the New York Times and other publications, delivers a crackerjack feat of storytelling that steadily administers the truth about capital punishment like a slow, toxic IV drip.

The story begins with the discovery of a body in 1982: Handsome, well-off Dorothy Edwards, a 76-year-old widow and resident of rural Greenwood, S.C., who “could have passed for 56.” Her battered corpse was found in her closet by a neighbor. He helpfully pointed out to the police a beeping alarm clock, a full pot of automatically brewed coffee and an open copy of TV guide — all conspicuously pointing to a time of death — before suggesting that the 23-year-old man who’d recently washed Edwards’ windows seemed a likely culprit. Within days, the police had arrested Edward Lee Elmore, a soft-spoken, docile laborer of very limited intelligence, with the feeblest excuse for probable cause: Edwards had written Elmore a check and one of his fingerprints was found on the windows she’d paid him to clean. Do I even need to tell you that Edwards was white and Elmore black?

After that came a mockery of criminal investigation followed by a mockery of justice. The police failed to photograph the bed where they claimed Edwards had been brutally raped or to retain the bedsheets as evidence. Other evidence passed through an unusually large number of hands (some of them unaffiliated with the investigation), or disappeared and then eventually reappeared (or not). No one bothered to check out that so-helpful neighbor who discovered the body and recommended a suspect. The medical examiner delivered a convenient but highly improbable time of death in a report that an expert would later liken to the work of a “first-year intern.”

As for the public defenders initially assigned to Elmore’s case, one was a racist who referred to his client as “a red-headed nigger.” The other was, in the words of a detective convinced of Elmore’s guilt, “drunk through the whole trial.” The judge made no secret of wishing to wrap things up quickly. He allowed the father of a prosecutor’s best friend to sit on the jury and incorrectly informed the jurors that those who didn’t support the death penalty were obligated to recuse themselves. He also plainly indicated that he considered Elmore to be guilty. The locally powerful lead prosecutor engaged in a colorful array of misconduct. In a week, Elmore was sentenced to death.

Elmore’s advocates succeeded in overturning his conviction twice. He was awarded two additional trials. In the first he was assigned the same incompetent defense attorneys (Bonner describes it as a “video replay” of the original trial) and in the second (which was allowed to contest the sentencing only) a committed but inexperience defender was unable to outwit a wily, unscrupulous prosecutor to mitigate the penalty. Elmore’s case changed that young lawyer’s views on capital punishment by showing him a legal system plagued by outright finagling: “not human error,” he told Bonner, “but human manipulation … We don’t have the right as a civilized society to pass this judgment.”

Eventually, Elmore’s case came to the South Carolina Death Penalty Resource Center and Diana Holt, a freshly minted attorney at age 36. Holt had overcome a childhood and youth marred by sexual abuse, drugs and divorce. She was convinced of Elmore’s innocence and the further she and her colleagues pursued inquiries that should have been made by his original defense team, the more convinced they became.

Bonner is clear that most convicts on death row are guilty; at issue is not whether they committed the crime, but whether mitigating circumstances — in particular, mental deficiency — argue for life without parole. That death sentences will be appealed is taken for granted, but what Bonner underlines is the institutional defensiveness and inertia that makes those sentences so difficult to overturn. South Carolina judges were extremely reluctant to admit that South Carolina state attorneys and law enforcement could be negligent or deceitful, or their fellow judges remiss. A state attorney (like the one assigned to Elmore’s appeal) might one day expound on a prosecutor’s solemn duty to pursue justice not just victories, then battle fiercely to uphold a conviction even he can see is unjust.

Perhaps most appalling to the average citizen, the emergence of persuasive evidence of innocence after a conviction is often irrelevant to the appeals process. A condemned man’s defenders must instead rely on persuading judges that his constitutional rights were violated during his arrest or trial. “Innocence alone does not entitle a defendant to a new trial,” Bonner explains. While there are good reasons for this principle, it has led to such grotesqueries as a state lawyer arguing before the Missouri Supreme Court that an innocent man ought to be executed even if the court found “absolute” evidence exonerating him of the crime. (To their credit, the justices on that court ruled that “It is difficult to imagine a more manifestly unjust and unconstitutional result than permitting the execution of an innocent person.” Conservatives on the U.S. Supreme Court apparently disagree.)

In Bonner’s expert hands, the twists and turns of Elmore’s appeals, and the gradual discovery of the travesties in the original investigation and trial by Holt’s team, make for excruciatingly suspenseful reading. Perhaps some observers might object to the application of true-crime-style narrative devices to an issue so grave. But we love crime novels and courtroom dramas for the same reasons that we ought to care about the perversion that is capital punishment in America; all of us, deep down, want to see justice done. If it takes a Hollywood story line to get us to pay more attention to the contrast between our favorite fictions and the world we live in, then that seems fair enough.